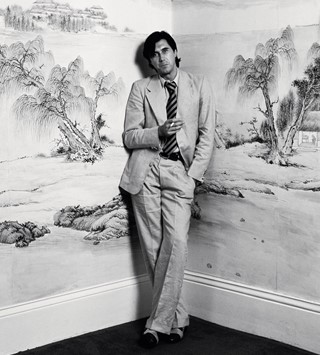

Amelia Abraham meets American photographer Paul Mpagi Sepuya, whose new exhibition – A conversation about around pictures – explores image-construction and digital self-fashioning

- TextAmelia Abraham

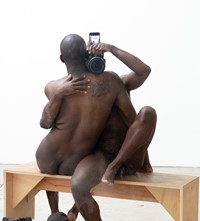

In the age of the iPhone, the act of photographing ourselves and others has become quotidian, an intimacy that we take for granted. Yet spending some time with the images in American photographer Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s new solo exhibition at Vielmetter Los Angeles, A conversation about around pictures, prompts a more self-conscious critique of image-construction and digital self-fashioning. Ambiguous and layered, the photographs often depict men’s bodies intertwined, as seen through a puzzle-like and disorientating combination of mirrors, screens and lenses. This seemingly urges us to question who is viewing who – and how – in the eroticisation of queer and black bodies, as well as how we choose to represent ourselves in digital cruising spaces.

Taken between 2017 and 2020, the images bear the hallmarks of Sepuya’s earlier works. They are shot in his studio where he almost exclusively shoots, and only feature friends, lovers and acquaintances. Like the work featured in the 2019 Whitney Biennial, they conjure collage, but are not (a trick of Sepuya’s camera), and similarly to the images he currently has on show at The Barbican’s exhibition Masculinities. Skin tones interact with the clinical white of the studio and the imposing presence of a black curtain, which “signifies a history of studio portraits, delineates a space of action, and asserts inherent power and value for the quality of blackness itself”.

Below, we talked to Sepuya about the show, his thoughts and influences, and current reading list.

Amelia Abraham: Tell me about the title A conversation about around pictures. How did you choose this?

Paul Mpagi Sepuya: I’d been thinking about conversation pieces – those informal group portraits – enlightenment scenes of scientific studies. I was re-reading and amusing myself with Michael Fried’s thoughts on anti-theatricality and absorption, about the humour of a scene wholly disregarding the viewer yet caught up in the positions and gestures of looking, being seen, and creating scenes.

AA: You shoot people you know, friends and lovers in the intimacy of your studio. You’ve said you’re terrified of photographing strangers or street photography – why is that?

PMS: Ha, oh Lord, if I said I was terrified of strangers and street photography it was hyperbole but yes, I am not that person who would ever stop someone and say: ‘I have to take your picture.’ I make work with people I know, have known a long time, or am getting to know. But in some way, our relationship or knowing is structured or conditioned by the desire to see or be seen by each other. If someone commissions a portrait for a magazine or something, they’re occasionally strangers and maybe I’ll say yes. Even better when it’s someone I already know.

AA: You have talked about how ‘queerness and blackness exist in the space behind the curtain, at first conditioned by necessity and following that maintained by fetish and fantasy’. Can you say more about the curtain in these images?

PMS: The black curtain provides a material extension of the body and abstraction of blackness – as a condition and position – that allows making visible a kind of latent trace, otherwise obliterated by whiteness – in looking, the process of photographing, and the resulting works. The curtain is often just a backdrop, a marginal subject. In considering the blackened space created behind it, the overlap of the language of the dark room and darkroom, we can consider how blackness is a prerequisite for photography and social vision.

AA: For you, what is the relationship between the mirror and the iPhone?

PMS: The mirror creates a space that might just create a picture that has no need of a beholder. The making, exhibitionism and voyeurism are entirely within a closed circuit. The scanning screen of the iPhones makes visible a part of the picture that is otherwise unseen by my camera, and points towards a trajectory of escaping that circuit. Dissemination toward another audience and another social economy of pictures.

AA: These works conjure digital cruising culture – was this deliberate?

PMS: Absolutely.

AA: What does the idea of a queer gaze mean to you?

PMS: It’s one that holds all aspects of friendship, the encounter, and exchange as potential and simultaneously charged.

AA: Do you think about your work as having a political imperative in terms of queer black representation, or is it just the work that feels most natural to make?

PMS: My interest is this: I want it to be impossible in the present or future to make an exhibition about the past, present or future technology of photography itself without acknowledging the fundamental position of blackness as material, or blackness and darkness as location from which and into which to look. I want an exhibition about photography that is not about identity, to be inseparable from the productive desire that structures queerness. Peoples’ interest in identity and politics will come and go based on this regime or that, but if we can assert ourselves at the foundation of the medium whether or not they want it, we will be there.

AA: Your previous work currently features in the Barbican’s Masculinities exhibition (which is temporarily closed until further notice due to the coronavirus outbreak) – how do those particular works deconstruct or play with ideas of masculinity?

PMS: The selection was the work of the curators in conversation with my New York gallery, team (gallery, inc.). I trust the curators and am interested in the ways in which the work I make contributes to the conversations they’re organising. Masculinity is not a subject that I am directly engaging with or thinking about in my work. What I mean by that is I’m not beginning any project with the idea of ‘how can I question masculinity?’ But the work is dependent on conditions of male homoerotic relations of play and looking, which is entangled in masculinity or a kind of it.

AA: Are there any upcoming photographers or queer artists whose work you have felt inspired by recently?

PMS: You have to check out two young, self-taught photographer friends in Los Angeles: Clifford Prince King and James F. Garcia. Their work was included in the project I presented at the Whitney Biennial. I get invited to be on panels and juries a lot and am actually overwhelmed by how much good work there is out there by young artists that I wish could get recognised.

AA: Finally, what are you currently reading?

PMS: I’m re-reading Claude McKay’s Romance in Marseille, but it doesn’t have anything to do with my work other than an overall interest in a kind of decadent Harlem Renaissance literature. I was last reading N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, which was excellent, and also nothing to do with my work. I needed some black sci-fi fantasy.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya: A conversation about around pictures is at Vielmetter Los Angeles, visit the online viewing room here.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s self-titled book is out now, co-published by Aperture and the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis.