The Barbican’s New Show Proves Masculinity Doesn’t Always Have to Be Toxic

- TextPeter Yeung

The photographs at the Barbican’s latest exhibition Masculinity: Liberation through Photography stick it to the Trumpian man of today, writes Peter Yeung

A hairy and wrinkled buttcrack, an extravagantly rotund belly and sagging nipples that gave in to gravity decades ago are what first greet the eye at the Barbican’s latest exhibition Masculinity: Liberation through Photography. They form part of John Coplans’ Self-Portrait (1994), a grid of 12 intimate yet intrusive closely cropped photos that the British artist took in his seventies, challenging the idea of youthful male beauty.

These are far from the thrusting Greek marble figures that are found in the British Museum or the bronzed torsos of Love Island. Instead, in a deft move from curator Alona Pardo, they signal a rather different vision of masculinity – one with all of its warts and imperfections on display. It’s masculinity laid bare, so to speak, and whether it is appealing to the eye very much depends on the beholder.

Bringing together 300 works by more than 50 artists, the Barbican’s photo blockbuster explores how masculinity has been “experienced, performed, coded and socially constructed” from the 1960s to today. It navigates from queer identity, to black bodies, the role of power and patriarchy, the female gaze, hypermasculinity, and fatherhood. It’s a plurality that touches almost every aspect of life.

But as Jane Alison, head of visual arts, explained at the opening it is an attempt to “start a conversation” in the context of the rise of toxic masculinity. While acknowledging the undeniable damage that some forms of masculinity continue to cause, there are more positive forms of this social force. “Patriarchy is not synonymous with masculinity,” added Alison. “It can be beautiful, tender and vulnerable.”

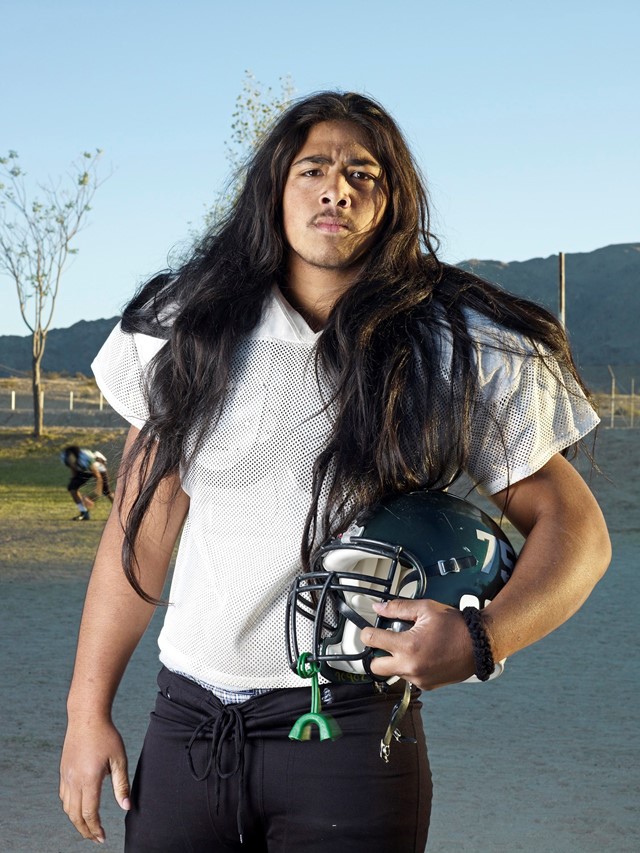

One richly fertile subject of this reassessment is the mythic American cowboy, a stoic yet chivalrous icon often clad in denim, boots and a hat. A whole genre of cinema came to be dedicated to this ideal, mostly airbrushing out the errant realities. But the Deep Springs series (2017) by Sam Contis, shot at an all-male university and working ranch in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains, shows them tenderly sitting in the fields and collecting chicken eggs. Isaac Julien’s monochrome portraits, shot between 1999 and 2000, beautifully depict homoerotic desire between a young Hispanic man and white cowboy – longing gazes are shaded in blue, a tender embrace covered in warm red.

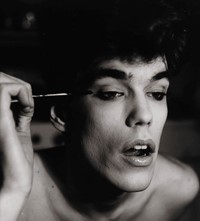

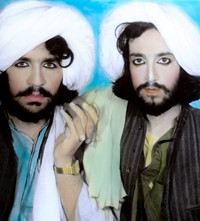

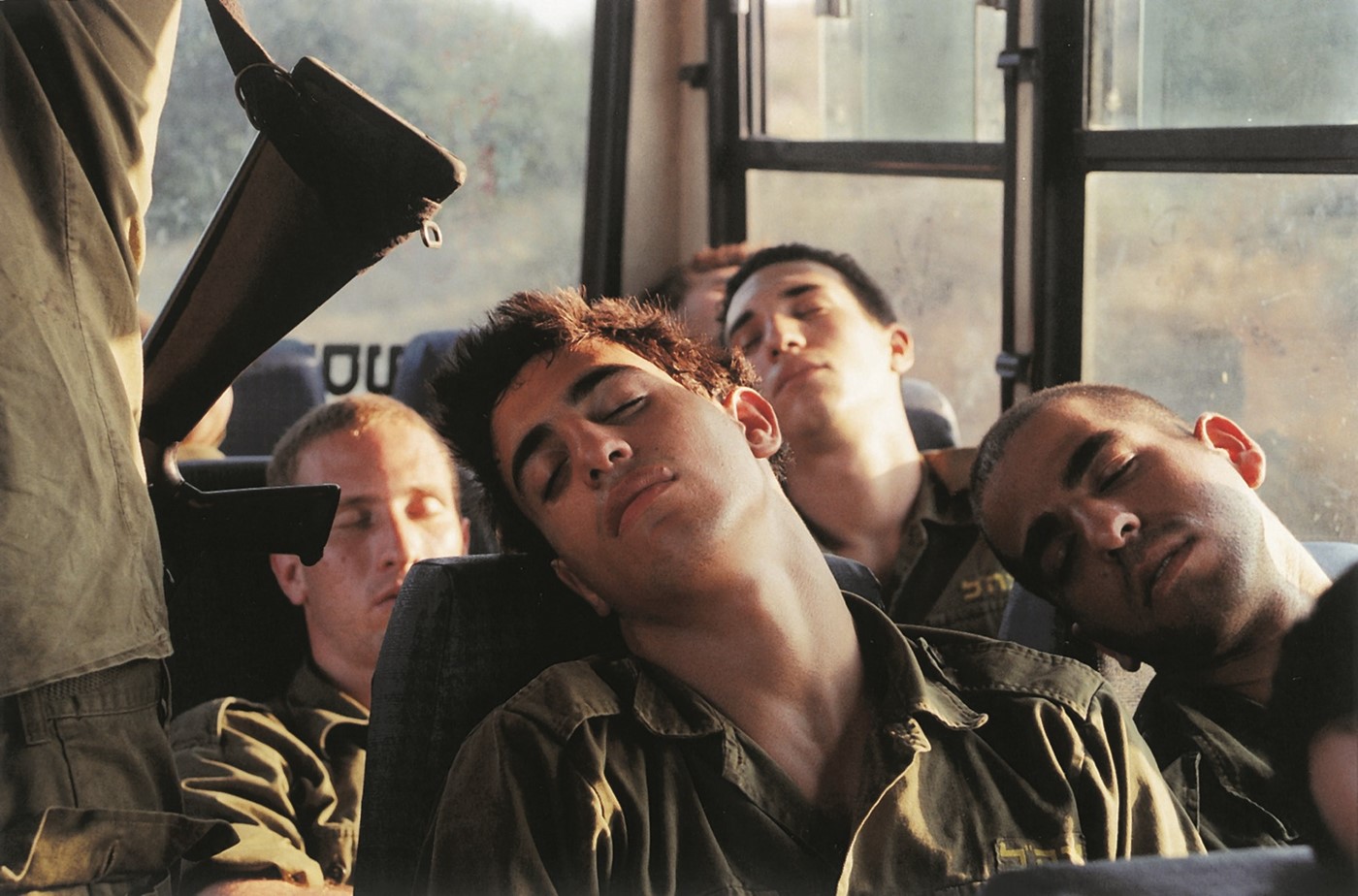

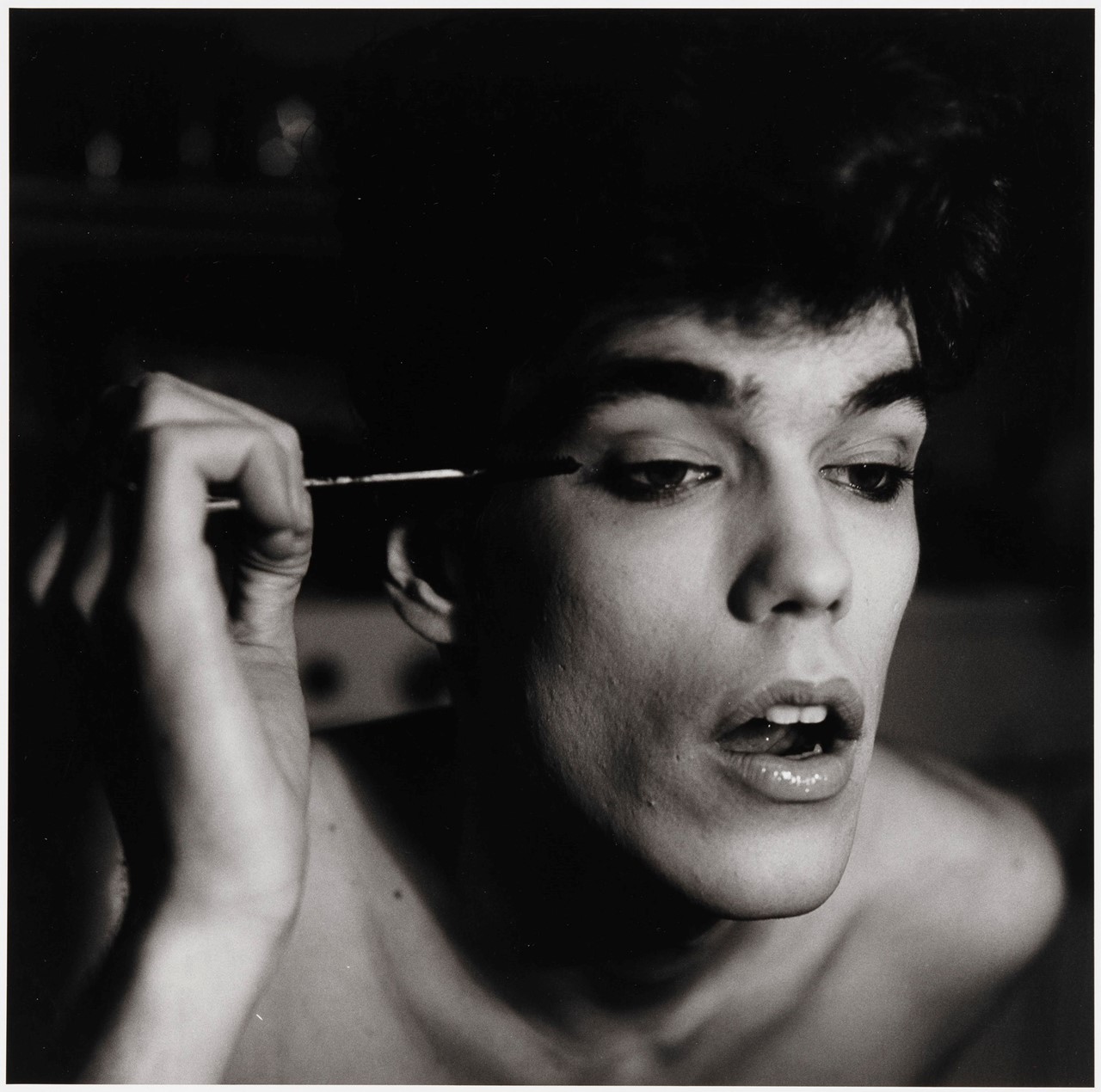

Masculinity has also been used as an instrument of war, as seen in the striking newspaper cuttings of Wolfgang Tillmans and the wall of portraits by Piotr Uklański, where Hollywood actors such as Marlon Brando, Clint Eastwood and Leonard Nimoy are dressed as Nazis. But the Taliban portraits, found by Magnum photographer Thomas Dworzak in Afghanistan following the US invasion in 2001, give a joyous look behind the curtain. There’s a real 1990s boyband vibe, as soldiers wearing make-up hold hands in front of backgrounds of lovely white cottages, classic English gardens and colourful vases of flowers – disrupted only by the presence of AK-47s.

The body itself is explored: as wrestler, bodybuilder and athlete. Robert Mapplethorpe makes an appearance, but rather than his famed transgressive photos of black men, there are shots of an obscenely bulky Arnold Swarzenegger in 1976. Better yet is Akram Zaatari’s Bodybuilders (2012) collection, produced from damaged negatives of Lebanese weightlifters, and blown up to huge prints some three metres long. They clench and contort, a looming presence, but the graininess of the images show the fragility of it all. But the best of the bunch is Jeremy Deller’s moving film So Many Ways To Hurt Yous (2010), linking the postwar decline of the working class to masculinity through the story of Adrian Street, a Welsh coal miner turned cross-dressing champion wrestler.

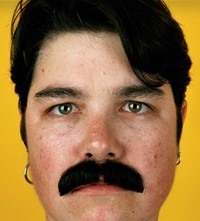

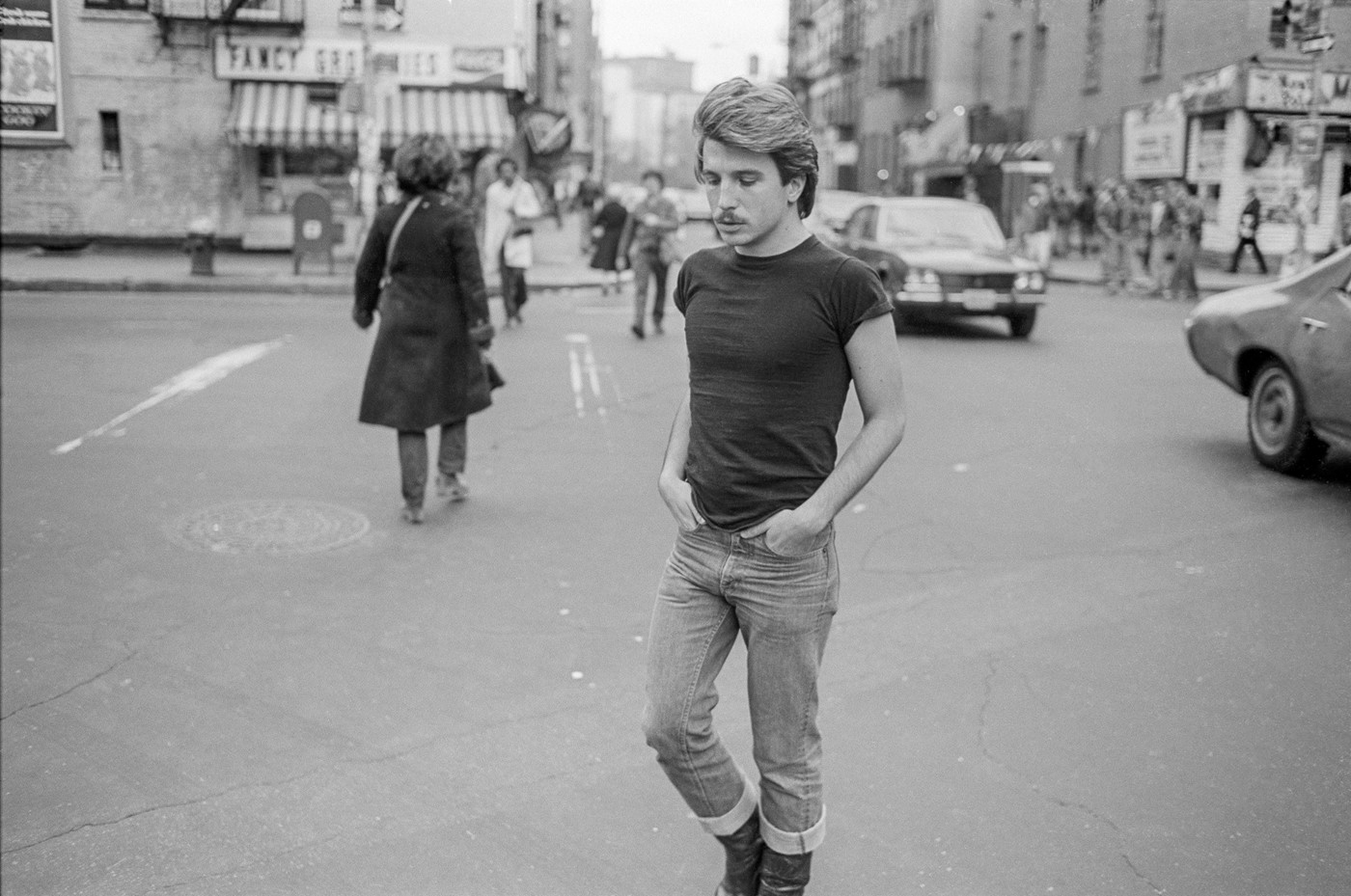

Throughout, it’s clear that in navigating these diverse forms of masculinity, photography – the OG of the male gaze – can be liberatory. Hal Fischer’s annotated 1977 series Gay Semiotics shows how the gay male aesthetic in San Francisco was able to appropriate the tight white vests and leather jackets of the traditional working class man. Nigerian photographer Rotimi Fani-Kayode attacks the castrating stereotype of the big black penis by replacing them with a large pair of silver scissors. Whereas, Laurie Anderson’s seminal Fully Automated Nikon (1973), subversively documents the men who cat-called her while walking through New York City’s Lower East Side.

These photographers stick it to the Trumpian man of today, with some shown peeing their pants, weeping uncontrollably or making cringeworthy orgasm faces. As a James Baldwin quote printed large on one wall puts it: “[The American ideal of masculinity] is an ideal so paralytically infantile that it is virtually forbidden – as an unpatriotic act – that the American boy evolve into the complexity of manhood.”

The message rings clear: masculinity doesn’t always have to be toxic, even if it often is.

Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography is at the Barbican, London, from February 20 to May 17, 2020.