A Dive Into the ‘Années Folles’ With the Luminaries of a Lost Generation

- TextJack Mills

Heroin or cocktails, Hemingway or Fitzgerald, Right or Left Bank – who won the Parisian postcode wars of the 1920s?

This article is taken from the Summer/Autumn 2020 issue of Another Man:

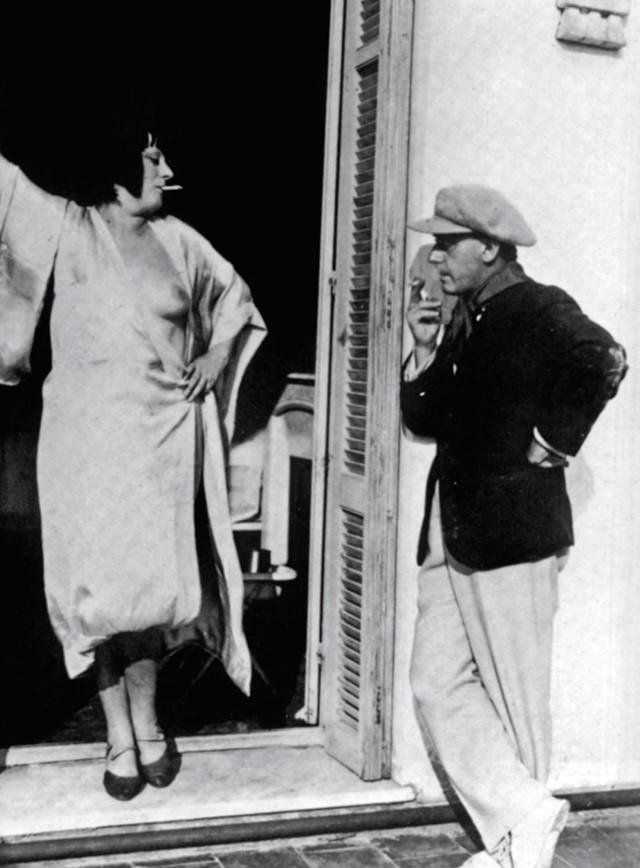

It’s 1922 in an area known as the navel of Paris, and Coco Chanel is making out with Igor Stravinsky. “The only man I felt attracted to was Picasso, but he wasn’t available,” Chanel would tell a reporter of her moment with the seminal avant-garde composer. Round the corner, where the 6th arrondissement locks horns with the 7th, a hard-boiled egg fight has broken out among patrons of the Café de Flore, by order of the boss.

“We discovered drugs, pederasty, travel, Freud, escape and suicide – all the elements of the sweet life,” wrote author Robert Brasillach of Montparnasse, the area south of the Seine where a flash of moral depravity and radical rubbernecking gripped interwar Paris. Montparnasse in the 1920s was the scene of an argument between André Breton and Tristan Tzara that killed Dadaism; where Picasso wrote in Cubism, and where Man Ray, Ezra Pound and Henry Miller – patrons of the so-called Lost Generation – consorted with escorts and presidents. There was a freeing sensation in Paris as the dust settled on the first world war, a feeling of vigorous collective unknowability, a total psychic resignalling. In the beau monde cafes of the Left Bank, homelessness shook hands with high society. Via heroin.

It also meant that the formerly cool Montmartre on the Right Bank to the north had lost some of its lead. Montparnasse felt ostentatious and untapped, a million miles from the tourism-choked Place de la Concorde. A rift formed between the Right and Left Banks that would feel familiar in any major global metropolis, the kind that pits north London against south, east Berlin versus west or LA versus New York City. With the benefit of a century of hindsight, which Bank truly won the 20s?

Montmartre was arguably Montparnasse’s genuinely strange uncle. There seemed to be a Right Bank version of everything Left: F Scott Fitzgerald was in Montparnasse, while his closest literary rival and disputed lover Ernest Hemingway stayed Right; the Bloody Mary was invented in Harry’s Bar in the 2nd arrondissement, while its rival cocktail Death in the Afternoon was brewed in the Left. Even car entrepreneurs Louis Renault and André-Gustave Citroën were in a Left-Right postcode war.

While the café scene of the south was smart, dressed and occasionally heroin-y, Montmartre was consistently intoxicated. Drinks at the Cabaret of Hell in Boulevard de Clichy were named after deadly diseases, served by a constabulary of monk waiters, and were often enjoyed by the surrealist André Breton, whose studio sat four floors above. Over in Pigalle, West Virginian performer Ada ‘Bricktop’ Smith opened a venue to introduce Europe to the Charleston, teaching everyone from the Prince of Wales to Cole Porter to dance. (Fitzgerald is known to have said: “My greatest claim to fame is that I discovered Bricktop before Cole Porter.”) Bricktop even threw author John Steinbeck out of her club for “ungentlemanliness”, only for Steinbeck to send her a taxi full of roses. Meanwhile, just south of the Seine, the queer playwright Natalie Barney ran regular ‘Sapho’ slams from her salon – on one occasion Mata Hari reputedly raced a horse naked through her courtyard.

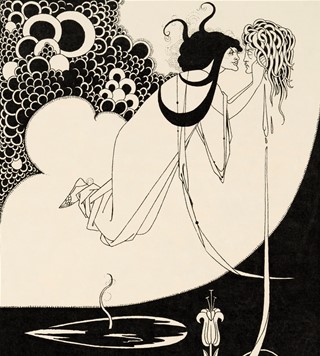

In 1929, the Left Bank picturehouse Cinéma du Panthéon was bought by Pierre Braunberger, the producer who would discover Nouvelle Vague directors Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais and Jean-Pierre Melville. Its clear rival in the north was Montmartre’s Studio 28, a politically charged screening room that Jean Cocteau called “the cinema of masterpieces, the masterpiece of cinemas”. At an early showing of Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s L’Age d’or – a short film that stuck its tongue out at the Roman Catholic church and its greying take on human sexuality – a riot ensued, with right-wing mobs smashing original artworks by Man Ray, Dalí and Max Ernst. A stone’s throw away lay the original Grand Guignol horror theatre, whose best-known performer Paula Maxa was murdered over 10,000 times onstage and was famously dubbed ‘The Most Assassinated Woman in the World’.

Not everyone imbibed the Parisian era known as the Années Folles. Princess Violette Murat moved to the south of France to live in an abandoned submarine, where she started an opium habit with the surrealist writer René Crevel. Others didn’t see beyond the physical appeal of an exciting new social movement. “At the Café de Flore, people are a little less ugly,” said the actor Juliette Gréco. But whatever it was – and for good reason, it remains unclear – it left something in the pipe for culture at large.

Paris in the 20s With Kiki de Montparnasse is published by Assouline.

The Summer/Autumn 2020 ‘High Art Pop Culture’ issue of Another Man is now on sale internationally. Head here to buy a copy.