“It’s not easy money, and anybody who says it is easy is either a fool, a supermodel or lucky”: Otamere Guobadia investigates the phenomenon of gay sugar baby-daddy relationship

- TextOtamere Guobadia

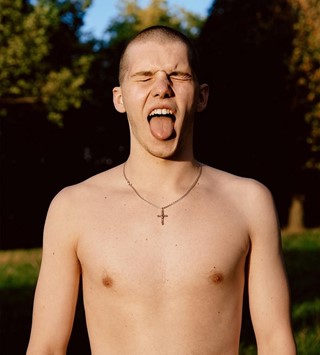

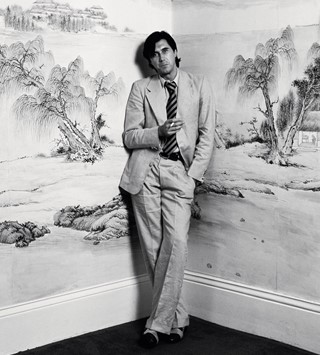

The sugar gayby, according to Patrick, one twink I speak to who identifies as such, is “an aspirational vessel”. You only need to look at the icons of gay pop culture – from the OG daddy whisperer Lana Del Rey, to our most recently cannonified Kim Petras – for an insight into this phenomenon. Our bratty, patron saints of kept boys and girls, with their French-tip manicured, Hamptons-spiced auras, bestow such lucky creatures with shining, elevated status. The relationship between daddy and baby is one imbued with a glossy romanticity by images such as these; a fairy-tale dichotomy with our daddies – virile, mysterious, Mr Big types with bottomless pockets – on one end, and our babies – impatient, spoiled, designer shopping bags in tow – on the other, locked in a sexy, pouty, Fifty Shades-esque battle of wills over where the private jet should land. The sugar baby of our imaginations, in the iconic words of Ms Petras, demands with every flick of their blinged-out wrist: “If I cannot get it right now, I don’t want it at all!”

This is the lush, enduring image of the sugar baby, but how much of this rings true in the real world?

The reality for most people engaged in this enterprise is far from glittering, and littered with compromise. Especially at the start. “At first all sugar babies are vulnerable,” says Patrick. These zeitgeist images have a pervasive effect: “We see sugar babies as above us, but really they’re not. Sugar daddies are above us,” he says. Our enduring idea of the sugar baby possesses a glamour divorced from the reality that those seeking these arrangements are often in a position of financial precarity, born not out of a desire for such glamour and excess but out of necessity. “We presume sugar babies as this kind of luxurious body,” continues Patrick. “But actually when we strip it back, sugar babies are coming from a point of essentially just wanting to earn more money because they themselves don’t have it.”

For some, the sugar gayby-daddy relationship is one of convenience. As Adam, a somewhat cynical financier, who often views these relationships in similarly speculative, monied, and pragmatic terms tells me, “wallet love” – an induced state of pseudo-affection brought about by cold, hard cash – is “about efficiency”. For a businessman like him, money creates a shorthand. He’s engaged a mixture of rent boys and sugar babies – the rent boys with pre-agreed upon terms and expenses to save time and manage expectations, and the sugar babies (or as he sometimes calls them “regulars”) beginning as the rent boys with straightforward money-for-sex quid pro quos, the inner workings we might be more familiar with.

The rules of engagement for sugar babies, however, and how these relationships come into being, naturally have more varied and liminal origins, with no set formula. Patrick, who has primarily found his daddies on SeekingArrangement.com (a website for daddies, mummies and babies to connect) doesn’t like to talk money or hard terms at first. He sees this as an own goal. “You don’t want to shoot yourself in the foot by laying out a kind of guideline for this exchange if you are marketing yourself lower than what that sugar daddy had in mind for you anyway,” he says.

Sugar gayby relationships, when compared to their cis-het counterparts, come with their own idiosyncracies. These relationships have versions as broad as you can imagine, though the common thread that binds them together is an indulgence in fantasy. Largely stripped of the gendered power dynamic that informs traditional models of sugar baby-daddy relations, other dynamics blossom in their place – and in no place are these differences more evident than in the fantasies both parties choose to play out and along with.

“When I’m on Seeking Arrangement, I’m trying to build this illusion of an experience – it’s not an escorting service where I jump straight into sex” – Patrick

And for Patrick, who comes from a working-class background and has been financially independent since he was 18, fantasy, as well as finance, matters. He makes a distinction between more traditional escorting and sugar-infused affairs. “When I’m on Seeking Arrangement,” he explains, “I’m trying to build this illusion of an experience – it’s not an escorting service where I jump straight into sex.” And for him, the Pretty Woman make-believe necessarily cuts both ways. “It was just like a way of accessing the lifestyle that I couldn’t otherwise have.”

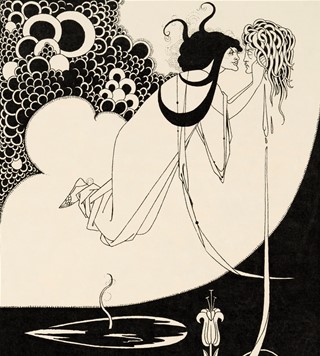

But beyond the fantasy of “wallet love” – of ‘boyfriend experience’ style intimacy generated by financial remuneration – another perhaps more delicate illusion is being spun. Often, “legit sugar daddies”, as Sebastian, one recently cut-off sugar gayby, puts it, “like to pretend that it’s something other than [financially] transactional,” he explains. “The only time I ever really use that language is when I talk about it with friends, because it’s a way of explaining a really complex thing,” he adds. There is a kind of simulacrum of tutelage. “I learned that he very much likes to see me as the student learning from him because he is a very, very, successful businessman,” Patrick explains. What becomes glaringly evident, is that some men with means want to role play a generational bestowal of knowledge, a Gatsby-esque attempt to relive the past, to reinvent it. They are attempting to mentor past selves vicariously by providing a fatherly, teacherly love that they were themselves denied by yesteryear’s climate of homophobia, by wisdom lost in the fires of the HIV/Aids crisis. The sugar baby-daddy relationship serves as an imitative ritual that almost calls back to the ancient practice of Greek pederasty – where the ‘Philetor’ (analogous in a sense to our modern-day daddy) would befriend (read: kidnap) the ‘kleinos’ (an adolescent boy), to embark on a kind of part-sexual, part-educational mentorship which would include expensive gift-giving. These unconventional relationships were not de facto abusive nor non-consensual, but it’s hard to truly judge by our modern moral standards.

“He loves to give me life advice,” Patrick says of one daddy, “but [in the underlying dynamic], I believe I have the power of the situation because he is on my borrowed time, which he’s unaware of. He thinks I am willfully seeing him for the enrichment of the exchange, whereas I am seeing him for the enrichment of the kind of benefits that he can give me: the money [a rent payment], the trips [New York, Paris], wherever. That’s why I dedicate so much time [to it].”

The seat of power in these relationships is fluid and spectral, and the understandings encoded within them are shifting and melting – even for the sometimes frugal and business-minded Adam, things are not always so clear-cut and contractual, and not without the complication of feeling and possessiveness. “I don’t buy the cliche of the sugar daddy and boy who agree on a ‘deal’ and stick to it, no emotions involved. I haven’t met anyone like that.” Adam, who considers himself to have been on the receiving end of many “pretend feelings”, believes that “most cases are like [his], [built up slowly and eventually with feelings becoming involved”. As my conversation with Adam continues, it becomes clear that pretense was not enough. He often found himself growing resentful of the boys he engaged for the partners and boyfriends they had outside of the relationship he had with them – what he described as “the real thing”. He elaborates somewhat mournfully: “even though some of these guys might look like [they] have chemistry with you ... they’re doing it for the money.” He believes that pretending is, to some extent, something that is present in all romantic relationships. “Spouses [pretend] to love each other, so you can’t blame the sugar baby for creating a big charade based on his survival instinct,” he opines.

These romanticised illusions – or delusions, depending on who you ask – do more than simply sustain what might be a mutually beneficial arrangement. They also function to bestow on what might otherwise be ostensibly sex-work – with all its corollary stigma – the perfumed haze of a novel. “I don’t feel totally cheated from the bad experiences I had,” Adam continues, referring specifically to the time a sugar baby conned him out of £22,000 in tuition fees. “After all, people want to be loved – and they want to be fucked – but people will take advantage of you or of situations if you let them. It’s their instinct ... a normal aspect of human relationships."

Of course, there are those gay sugar daddies for whom the men they keep are just accessories, a way of accessing youth and beauty without the need – or desire – to involve the carnal. “No one has ever done anything sexually [with Peter*] as far as I know,” Hector*, a producer friend of mine, tells me. “But there’s absolutely no pressure in that sense either. It’s a very non-thing. He’s very awkward and in himself. I can’t imagine that he’s ever [had sex]. He’s probably a virgin.”

“There’s an [unspoken] quid pro quo in the sense that you have to bring it ... the idea is that you go because you’re a fun time” – Hector

Unlike most, Hector didn’t meet his daddy online or on an app like Grindr, nor in a chance encounter, but rather through a sort of quasi-referral system. Peter saw a video project he and his friends featured in (it was not pornographic), thought they looked like fun, and they found themselves in a Vegas penthouse, all expenses paid, not long after. Hector has now become an enduring fixture of what he describes as “posse of neverending, artsy f*****s that [Peter] cycles on his trips as and when they’re available.”

But the pressure, to perform in other ways – to be permanently switched on, for example – can sometimes be overwhelming. “There’s an [unspoken] quid pro quo in the sense that you have to bring it ... the idea is that you go because you’re a fun time,” says Hector. The boys do sometimes face the chopping block if they slip into boring domesticity. “When people get boyfriends they’re often quietly dropped.”

“You can always perform it as a friendship,” Hector says, “and then suddenly you realise the stakes are weird when, for example, he visits London and that means you’re expected to be free the entire time.” This demand is one that has caused Hector some frustration. “Your time is his time and then you realise that it’s just not a normal friendship at all.”

But for some babies being made an accessory is not just part and parcel of the deal, but desirable in and of itself. “I definitely felt like property at points, and the funny thing is I liked it,” Paris, now in his early 30s, tells me of his younger days as a sugar baby. According to him, his daddy never quite made demands, but was “extremely persuasive” about things like how he dressed.

“He wanted me to look like a preppy jock and [when my aesthetic got more street] he wasn’t happy,” he elaborates. “It was nice to be valued and validated. I remember I went on a very fancy weekend away with his rich friends and their boy toys, and we were traded and compared,” he says of one particular trip. “I remember feeling very competitive and even proud.”

He met his daddy, Paul* (a kind of imposing, impossibly wealthy gay Lex Luthor-type), as a broke 20-something partying in a bar in Los Angeles. His story in particular is as much fairytale as it is maelstrom. The luxurious perks were undeniable: dinners, trips and a multimillion dollar, two-story, five-bedroom apartment, “panoramic views” to himself, for which he paid rent for something like one 20th of its value – but so were the corollary scandals, dramas, and dangers: assassinations, big-ticket fundraisers, sex parties and overdoses.

“He wanted me to look like a preppy jock and [when my aesthetic got more street] he wasn’t happy” – Paris

Recalling a holiday on an infamous European gay party island, he describes an iPhone orgy photo that sounds like something a Renaissance master might have painted. “He had [one of the biggest houses] on the island and hosted a massive afterparty. I’d just ‘broken up’ with him saying I wanted to sleep with other guys there. He said ‘OK, point them out.’ So I did and he invited them to the roof and it [escalated]. It was quite scandalous, and I was terrified, but in hindsight it was really hot.”

While there was no explicit demand that Paris make himself available for sex, incidents like this seem to betray a certain sexual entitlement, and that an unspoken quid pro quo underlied their affair. “It was definitely an implicit arrangement,” he explains. “There was a running joke that when he texted for me to go up for a drink I’d say ‘off to pay the rent!’, but I also enjoyed it. I found him attractive, he reminded me of my first boyfriend.”

Their relationship does seem, for all its melodrama, to be largely devoid of jealousy. They weren’t monogamous, and Paul kept other men. “At the end when I cooled things down, he had another younger guy. I once went up to see him on my own and the other guy was in his bed, and I tried to fit in but couldn’t, they were splayed out.”

“The next replacement,” he explains matter of factly, “died of a G overdose”.

The life of a sugar baby is work, which often has myriad tedious demands. There is no free ride in a fancy car – for the most part these men often exact a high price for the rewards they dish out; there is a trade-off of agency, megalomaniac egos and jealousies to be negotiated with, other babies to compete with, and sometimes even danger. “I wouldn’t do it again now,” Paris says of his sugar baby days. “It was a time and place situation with LA, I wasn’t doing it for money – it was the priceless experience, and people I met, and places I went, and I learnt my own value ... Oh, and the apartment of course,” he concludes.

“It’s not easy money, and anybody who says it is easy is, no offense, either a fool, a supermodel or lucky,” Patrick answers, when I ask what he would tell his younger, twinkier self about the life of a gay sugar baby. “It is an exchange, of your time and body and energy for their remuneration, and when you’re grafting – as sugar babies do – the currency of time becomes all the more precious. I’d tell myself that it requires long term dedication and planning. It can be whimsical but ultimately 80 per cent of your daddies will fall through. You have to work for the 20 per cent that’ll pull through.”

*Names have been changed