Bryan Ferry Speaks to Tim Blanks on the Art of Roxy Music

- TextTim Blanks

Speaking to Tim Blanks for the Summer/Autumn 2020 issue of Another Man, Bryan Ferry reflects on the way the band’s music was communicated through image

This article is taken from the Summer/Autumn 2020 issue of Another Man:

Bryan Ferry:

“I REMEMBER WHEN I SAW THE FIRST ROXY MUSIC ALBUM COVER IN THE WINDOW OF A RECORD STORE ON KING’S ROAD. IT WAS THE NIGHT BEFORE ITS RELEASE, I WAS PROBABLY DRUNK... YOU FELT YOU’D DONE SOMETHING THAT WOULD STOP THEM IN THEIR TRACKS, THERE IN THE STREET, NOT IN AN ART GALLERY. TO ME THAT WAS REALLY IMPORTANT”

There are still people who believe that the 21st century began on 16 June, 1972, with the release of Roxy Music’s debut album. They have a point. Think of music 50 years before 16 June, 1972. Think of it 50 years after. That album perches on the apex of a modernity that is surreal in its timelessness. “It’s great when you don’t pay attention to what is happening at the time,” says Bryan Ferry now, the man who made Roxy Music.

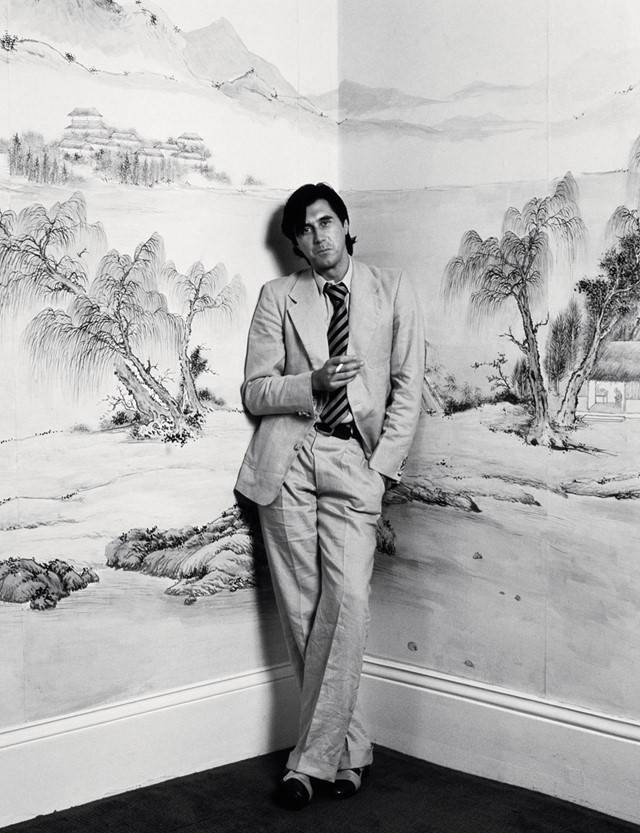

The first photo I ever saw of Ferry was in Melody Maker at the end of 1971. The astonishingly prescient music journalist Richard Williams had identified him as rock’s latest rara avis. At that time, Ferry was in a room on Kensington High Street, with the bones of a band he’d called Roxy. He had long hair and he was wearing double denim. When I tell him that, he dryly observes, “It’s now coming back into style.”

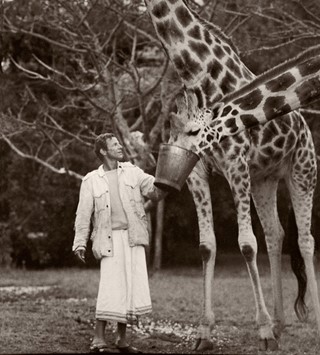

That first brush with fame identified Ferry as a fine arts graduate from Newcastle University, from which you could assume an association with Richard Hamilton, the legendary godfather of Pop Art, who taught at Newcastle. True, Hamilton was in charge of Ferry’s first year. “He was a powerful personality, and we were all very much in awe of him,” Ferry says. “He’d be upstairs in his studio working on his own. It was one of his strongest, most creative periods, when he was working on the Large Glass and his deconstruction of The Bride Stripped Bare. So beautiful. He sort of became our tutor. There were about 20 of us. He’d give us a talk on a Monday, pop in to see what we were doing, wander around in his white Levi’s jacket and white jeans with his cigar and his Karmann Ghia parked outside. Very cool. Richard was our conduit to Marcel Duchamp. He was a great thinker. Very articulate, unlike a lot of artists. Warhol, Jasper Johns, they were following Richard, so even if America was the place to be, it felt like where we were was also the place to be.”

“[Richard Hamilton] was a powerful personality, and we were all very much in awe of him. He’d be upstairs in his studio working on his own... He sort of became our tutor” – Bryan Ferry

But contrary to legend, Hamilton didn’t single out Ferry as special in any way. “We weren’t hanging out,” he says. “I was also dabbling in my first year. I had a band, I was just tentatively finding my feet with music. Richard had no interest in that, he couldn’t have cared less. So I was fringe because I was doing music as well. Later, when I was successful, he was aware.” One particular memory nags Ferry for a while, then it finally comes to him. After one show, Hamilton came backstage and greeted him with an exultant, “MY GREATEST CREATION!”

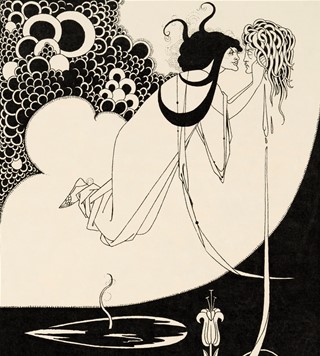

Hamilton had clearly grasped how he had subliminally informed Ferry’s self-creation. In January 1957, before Pop Art was even a glint in Pope Andy’s eye, Hamilton defined it like so: “Popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business.” Oh, how we love a prophet. The mix of idioms in Hamilton’s 1961 painting Pin-up might equally have contributed to the budding sensibility that would shape Roxy Music. Ferry also namechecks Hamilton’s $he from 1958, with its fragmentary vision of American consumerism: sex and appliances. In every dream home, a heartache.

Ferry acknowledges that Hamilton’s interest in collage was a defining influence: “That played such a part in the first Roxy album. It was a collage of ideas. Even within certain songs, it changes mood, so many ideas concentrated within one song. All the songs are quite different anyway, so that opened all sorts of possibilities. But I don’t think one should intellectualise too much about music and that’s why I was doing it in the first place, I wasn’t an intellectual. I felt it was just a more performed creativity to get into. Plus I’d seen Otis Redding on the Stax roadshow in 1967 – I hitchhiked down from Newcastle to see him, and I thought he was the greatest thing I’d ever seen. I loved the painters that I loved, but when I heard that music played live to an audience of devotees it took on a religious fervour I hadn’t experienced standing in front of a painting.”

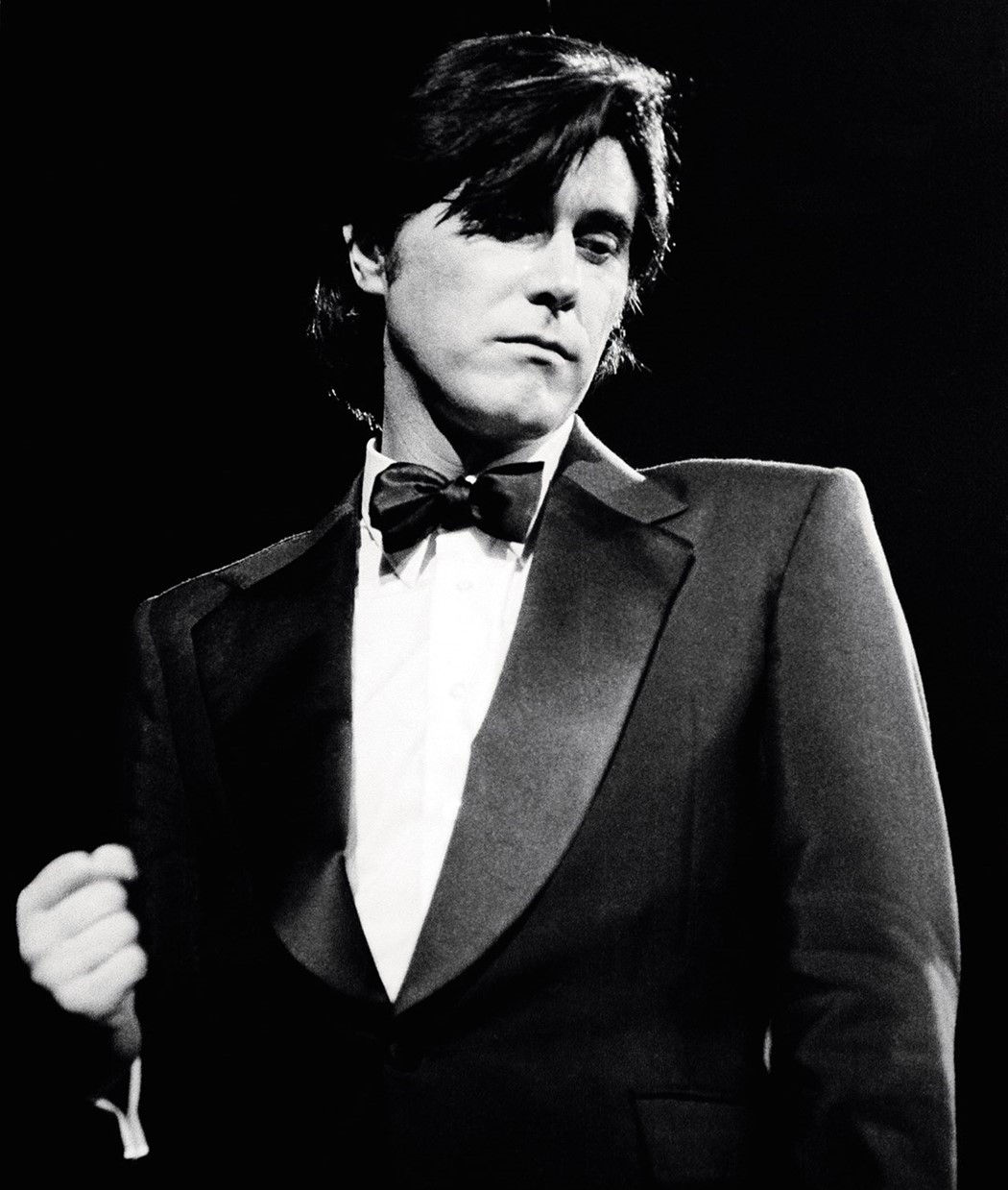

Think of Otis as Ferry’s peak drug, a hit of something so addictive that he spent the rest of his life chasing the rush. “Occasionally you get it with an audience yourself, where you feel that you’re representing yourself in the best possible way by performing a song well, with the right blend of elements you’re proud of, that people appreciate. Certain songs are tough to perform because you feel so moved when you’re doing them that you can hardly get through them. You feel you’re going to break up. Mother of Pearl is one of those, when you feel: ‘How did I get this so right?’ What is it? It’s words and music, but put them together and they conjure up a mood and a feeling that affects me greatly, and when I feel it affect an audience, it chokes me up.” He actually chokes up as he says that. I choke too. You really do want to know that one of your favourite artists feels the same way about one of your favourite songs as you do, especially when he’s the person who wrote and sang it in the first place.

Ferry arrived in London in 1969 with every intention of becoming an artist. The first place he lived was a studio on City Road, off Old Street. This was decades before the gentrification of the East End. A proper, freezing, old-style New York artist’s loft, once home to the painter Richard Smith, it had achieved a kind of immortality as the location of a wild party filmed for Pop Goes the Easel, Ken Russell’s legendary 1962 documentary about Swinging London’s art scene. “I was supposed to be painting, but I was too busy writing songs,” Ferry remembers ruefully. That’s what he said when the artist Mark Lancaster asked him what he was up to. “Oh, what songs?” asked Lancaster. “2HB,” Ferry replied. “A song about a pencil?” Well, obviously... not. Recorded for Roxy’s debut, 2HB is a poignant paean to Humphrey Bogart and the enduring power of the Hollywood icon. Listen to its mesmerisingly delicate mesh of piano, sax, electronics and vocals and marvel that this was one of the first songs Ferry ever wrote.

He insists that the recorded product was very much a band creation, giving full credit to electro-boffin Brian Eno’s manipulation of the sound. This is Bryan Ferry in revisionist mode, secure now in his accomplishments, able to acknowledge the work of others. “We got on really well musically,” he recalls. “In that honeymoon period, one liked everything anyone did. It felt exciting. Making any kind of coherent sound was interesting. I didn’t have a piano on Kensington High Street. I invented some of those tunes on a harmonium. So then to hear them come together in a band...”

It still surprises when musicians say they never listen to “the old stuff”. I wonder if Ferry ever goes back to the well to refresh himself. “Only when I’m referencing a song, as in, ‘Oh, how did we do that?’ The first album is so interesting, so many ideas. Eno called it 12 futures crammed into one song. You never need to make another album, this is it, kid.” It is intriguing that Ferry returned to some of the songs later – 2HB included – to strip them back, re-record them with more space. Take that as a metaphor for the arc of his career, from glorious clutter to streamlined elegance.

“I studied art, I had a band at college, I felt I was in two parts of myself... But when I combined the two, it was incredible. This is what I was meant to do” – Bryan Ferry

But we’re here to talk about the art of Roxy Music, specifically the way content (the music) was communicated through style (image). “Yes, they were an art project in a way, and also a way of getting away from art. There was some – it’s a word that is used too much – physicality. I studied art, I had a band at college, I felt I was in two parts of myself. One was the physical thing, the emotion, when I was singing and there was a passion about it. The art side was more thoughtful, to do with reasoning things out. But when I combined the two, it was incredible. This is what I was meant to do.”

To truly appreciate the impact of Roxy’s first album covers, you’d need to propel yourself back to a very different Britain. One of the things that struck me most about the 2011 movie version of John Le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy was how dismal its depiction of early-70s London looked. But it was set just when Bowie was unleashing Ziggy Stardust, and Ferry was launching Roxy Music. Somewhere other than MI5’s grey, grim world, a new breed of glamorous young nightcrawlers was exploding into life. It just proves that context is everything.

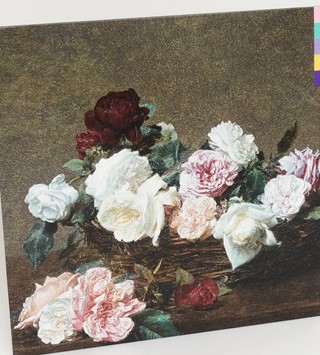

At the time, Vogue magazine was flummoxed by Roxy’s imagery. “It was kind of underground, which I think is rather cool,” Ferry says now. “I remember when I saw the first Roxy Music album cover in the window of a local record store on King’s Road. It was the night before the record’s release, I was probably drunk. It was just a fabulous thing. You felt you’d done something really good, really interesting that the man in the street would see. Stop them in their tracks, there in the street, not in an art gallery. To me that was really important.”

Refresher: Hamilton’s Pin-up. Ferry picks up the story behind that cover: “I saw Antony Price at a party in Holland Park. I didn’t actually talk to him, I might have said hello. Then I went to this club called the Speakeasy in Margaret Street where you used to see Hendrix. How I got in there and how I could afford to buy a beer, I don’t know, but I saw this guy at the bar with amazing hair and I said, ‘Oh hello, I met you the other night.’ It was Antony, of course. Whether he thought I was trying to pick him up, I don’t know. But we were just finishing the album and he looked like a like-minded person so I asked if he could help us do the cover. I called him from a payphone on King’s Road and I remember he was quite Yorkshire. ‘Oh, what do you want?’ But he was the coolest designer around. I think he was designing for Stirling Cooper then. So I was quite determined to get this to work, standing on this wet London street.”

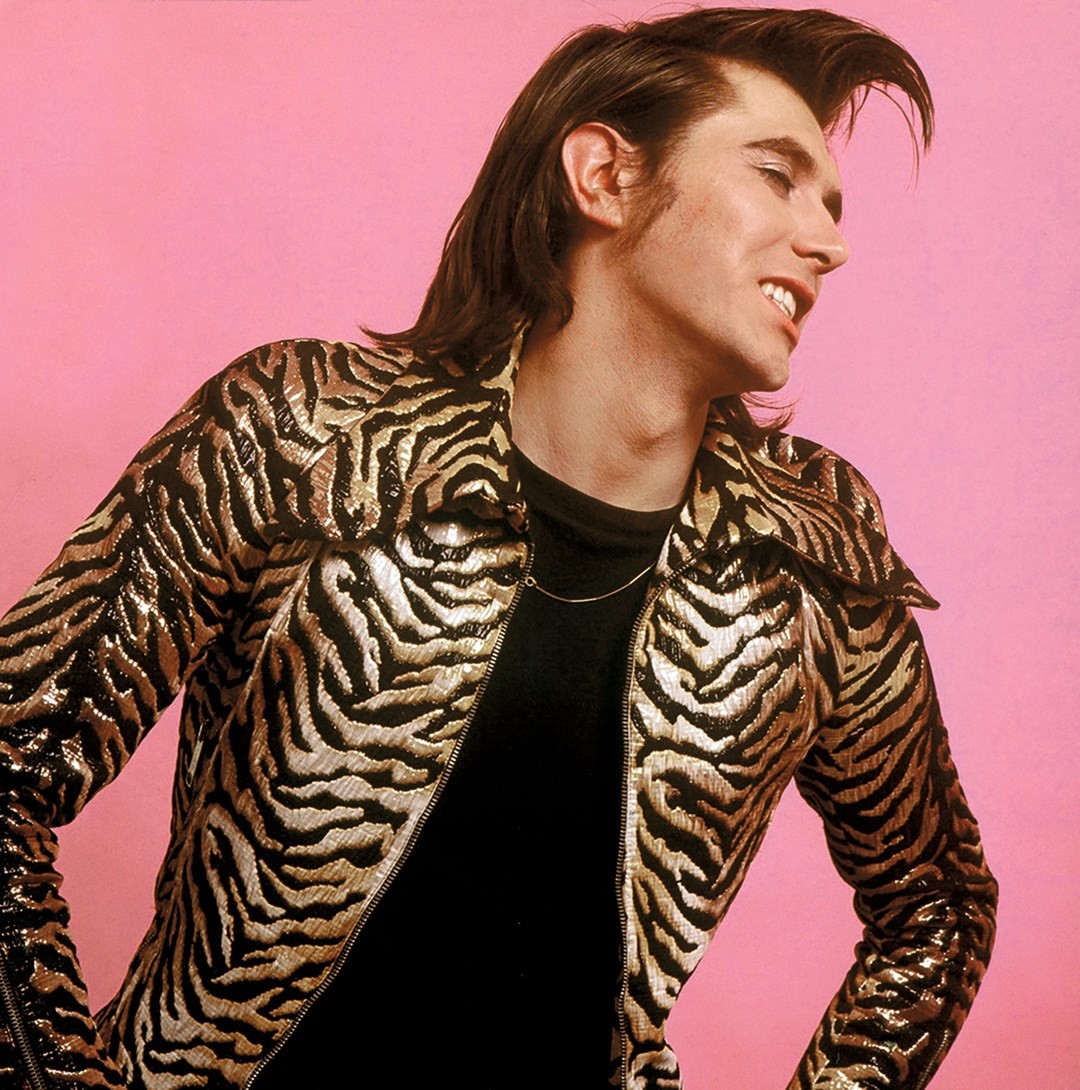

Fast-forward a week. “I wanted something that would reflect the music, amplify the feel. And Antony was just genius. It all came together like magic. I can’t remember if he had the clothes or made them, but we had the photographer Karl Stoecker, an impossibly good-looking American who was married to Errol Flynn’s daughter. And the model Kari-Ann Muller, who was like a dream fan, clutching a gold disc. Remember, you couldn’t immediately see what you had, three days later if you were lucky, so we went to Karl’s manager Octavian von Hofmannsthal’s house to see the photos, and it was a dream come true to see these wonderful images we’d created.” The cover, art-directed by Ferry’s college buddy Nick de Ville, was subsequently graced with deco-edged postcards of each band member, like pin-ups, mounted on “a piece of that sticky stuff you put on kitchen tables”. Ferry says he was like Darryl Zanuck, the producer adjudicating over the different elements. As for his own postcard, dressed as a lamé-clad greaser, he says now that he “looked better than reality, like he’d never be seen again”. Which is a hell of a lot more positive than he felt about his singing. “Awful,” he says dismissively. “I hadn’t quite found the keys, I should have taken them down a bit.”

Ferry wrote most of the songs for the band’s second album, For Your Pleasure, holed up in de Ville’s remote cottage in Derbyshire, banging away on his Hammond keyboard in solitary splendour. “I must have taken provisions, because I certainly couldn’t cook, but I was just full of energy, inspired by the fact that we’d made one album and keen to make another. I felt I had to be more articulate. I thought, ‘Oh my god, people are going to listen to this stuff.’ So the lyrics are 100 per cent stronger. The influence was anything I’d ever heard or seen or read.”

Look no further than album opener Do the Strand, a dance craze compendium for the ages. “I wasn’t trying to do Cole Porter, but the fact he referenced contemporary things in his songs must have struck a chord. Lolita. Guernica. I must have been thinking about him because he was the main man with those kinds of references.”

“I wanted something that would reflect the music, amplify the feel. And Antony [Price] was just genius. It all came together like magic” – Bryan Ferry

And then, the monumental In Every Dream Home a Heartache, a song whose dystopian grandeur has assumed the status of modern classic outside any life it ever enjoyed within the vinyl grooves of For Your Pleasure. “I must have been thinking a bit about Richard [Hamilton], the consumer thing,” Ferry muses. “Here’s a guy in the song who has everything and nothing. That’s a very tragic resonance throughout time, people who think they’re trying to get the world and they have nothing.” Inquiring minds need to know whether that was his own response to Roxy’s success. “I always wrote as a character. In some songs it rings more true to me, then there are others that are obviously me assuming a role. As an artist, you have to do that otherwise your horizons would be so limited. You have to expand your consciousness to become someone else, to become another ‘me’.” So rest easy – it wasn’t Bryan’s mind that was blown by the inflatable doll.

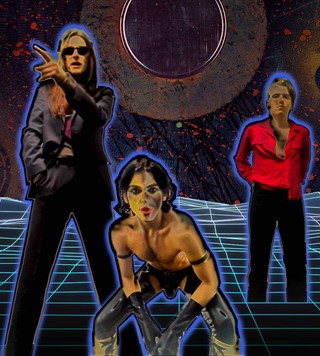

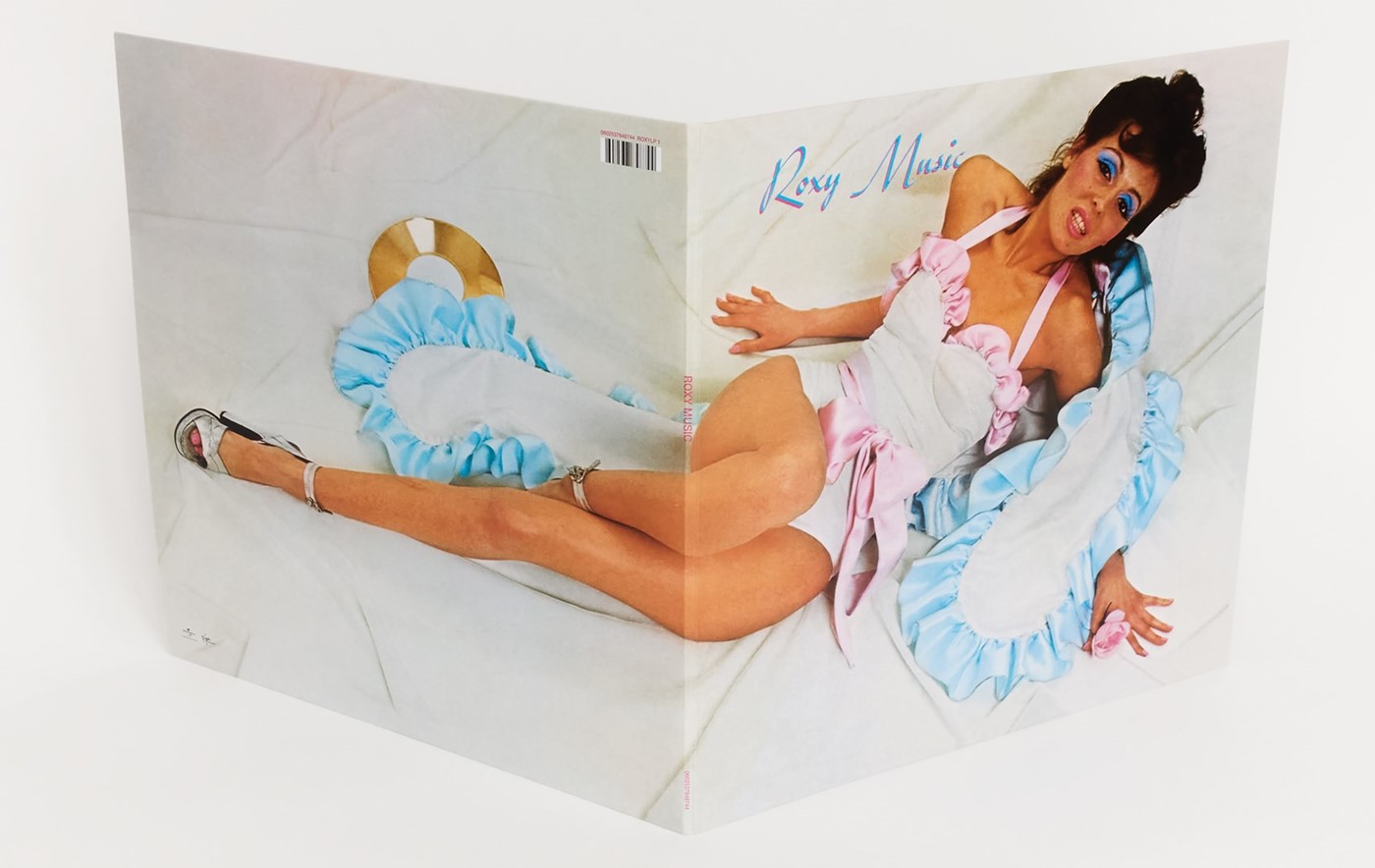

Ferry compares the first album and its cover to a chocolate box, a display with all these different flavours of music. “The next one was much darker, more knowing, more 70s, sadder, more sharply drawn. And the cover caught that. One of Antony’s models was Amanda Lear. We thought, ‘Let’s get Amanda in black PVC and I’ll be a chauffeur with a Cadillac, rather like the photo Richard Hamilton did with Robert Freeman in the open Cadillac. So we found this beautiful car. First we tried to photograph it outside but that didn’t work, so then we did it in the studio, like a car showroom, with PVC on the floor. And we got this guy to do a sci-fi panorama. That’s actually Las Vegas in the background.”

Price sketched out the cover beforehand. “Antony was steering, but it was me controlling ideas. I saw myself as the overall director, with Antony as the brilliant cameraman, as Eric [Boman] did with Country Life. A dream team. Karl Stoecker had moved to Milan after Stranded. But that was a good trilogy we did with him. We loved those women, we loved how they captured a certain kind of glamour. Not S&M but something tough, urban...”

What makes it even more glorious in hindsight is that it could easily have been just that one single magic moment. No one had a clue what would happen next. “Yes, we had no idea,” Ferry agrees. “That could have been the only one.” And what would the world have been like without Roxy Music?

Actually, if it had been a one-off, it would have fitted in a curious way with Ferry’s fanboy fervour for Marcel Duchamp. “Duchamp was always about reason and thought and ideas. He created some incredibly interesting pieces and then it was, ‘I don’t really need to create any more’, like he’d rather cleverly said all he wanted to say and didn’t need to impress anybody. And he just enjoyed his life in New York, giving advice to Peggy Guggenheim. But the body of work is enough for us to still be talking about it now. When I’m on tour, I always go to the museum in Philadelphia. It’s so cool, so knowing, so detached. Very French. You know how TS Eliot is so clever, with all the right words arranged in the right way? With Duchamp, it’s ideas, it’s visuals. There’s a mystery in Duchamp, which there is in Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker and Jimi Hendrix.”

Surely it’s something as fundamental as the mystery of creation. How are some artists so blessed with supernal talent? “It’s great when you see something that works,” Ferry says. “As a person who likes to sing other people’s songs, I have come across songs which are just so perfect, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, say. How on earth could they get things to fit together so beautifully? Some of Cole Porter’s things as well. He’s like a wise guy but he’s got such depth of feeling. To get the right words to convey these depths of emotion...”

Porter’s art was famously his armour. “Very much so,” Ferry agrees. “It’s how I judge myself, through my work rather than me as a person. ‘Bryan Ferry’ is kind of boring really. I do try to follow the Duchamp principle: make your life as interesting for yourself as you can. I have a great life at the moment, in balance with my work. Now I try and do that in the daytime. I used to work at night a lot, in fact, I had no life at all for about ten years and then I felt a backlash. I’ve got to live a bit. So I took my foot off the gas. But now it’s firmly back on.”

“It’s how I judge myself, through my work rather than me as a person. ‘Bryan Ferry’ is kind of boring really. I do try to follow the Duchamp principle: make your life as interesting for yourself as you can” – Bryan Ferry

We’re talking about a mutual friend and I mention that I think he’s bitter because he feels he did things first and other people got the credit. “Join the party,” Ferry chimes in. “I saw that happen too. But it’s not very good to ever resent that. One should always be open-armed and embrace things, it’s the only way to be.” I wonder if his equanimity is due to the fact he finally feels recognised in America. He says he had the best tour of his life there last year. He finally feels appreciated.

Ferry tours a lot now, like he’s making up for wasted time. “Not wasted, but there were quite a few years when I was struggling to try and find the right thing to do with my time. They were confused years. But when I listen to work from that period, I can hear good things. The album I made called Mamouna didn’t do well commercially but it’s one of the most interesting things I ever did. It’s very emotional. I was listening to stuff for the new tour this weekend, and some of those songs I really like.”

The last album he released was 2018’s Bitter-Sweet, officially by ‘Bryan Ferry and His Orchestra’, recorded in 1920s style following his appearance on the TV series Babylon Berlin, set on the cusp of the Weimar Republic’s collapse and Nazism’s rise. Ferry features in the show, performing his own songs retooled for the Jazz Age. “When they got to my bit, I had to look the other way, because I hate seeing myself. Antony will tell you, I never had the confidence.”

Bitter-Sweet is perversely true to the spirit of everything he’s ever done, cherishing the afterlife of his classic songs and burnishing them for new ears, pulling off the remarkable feat of re-modelling the 1920s sound for the 2020s. Just as remarkably, it’s not nostalgic – there is too much life in the music. It is one model for the graceful ageing of an artist. Superficially at least, it may sound like his old rival David Bowie took a radically different route with Blackstar, but in the end, both records are about acceptance of the inevitable. And at least Ferry has more leeway to further explore the notion... “There’s not really much time to do that,” he says, with perhaps a hint of rue. “The record I’d like to recreate is Bête Noire. I couldn’t quite get over the way that sounded.” I can’t second that emotion. Even as we speak, Bête Noire is playing in all its croony tristesse.

The Summer/Autumn 2020 ‘High Art Pop Culture’ issue of Another Man is now on sale internationally. Head here to buy a copy.