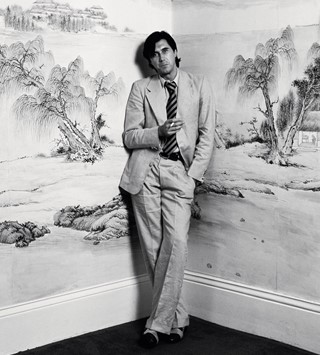

American artists McDermott and McGough have transformed Studio Voltaire into a space honouring the 20th-century poet – here, McGough explains why

- TextDean Mayo Davies

If you’ve never visited south London gallery Studio Voltaire, you’d be hard pressed to wonder what it looks like usually. Today it stands transformed into an immersive, secular space honouring Oscar Wilde, the 20th-century poet, playwright and gay rights precursor whom even his string of bon mots couldn’t save.

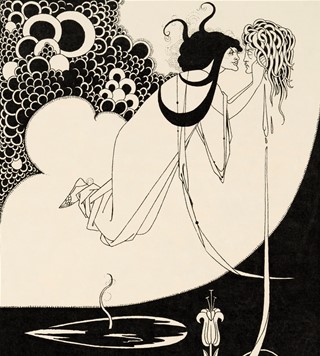

Wilde’s wit was notoriously divorced – and claimed – from the practising homosexual after he was thrown in (Reading) Gaol, and ultimately on the scrapheap, dying in bed at Paris’ Hôtel d’Alsace, aged 45. That peripeteian tragedy is backed by another one: that somehow being gay was viewed as a new world threat by society when instead it’s an extremely traditional predilection. There are none more historic than the ancient Greeks.

Covered in Aesthetic movement wallpaper, with stained glass and a statue of Wilde up front, The Oscar Wilde Temple runs until next March, conceptualised by American artists McDermott and McGough and curated by ex-Guggenheim/Pompidou/Palazzo Grassi talent Alison M. Gingeras.

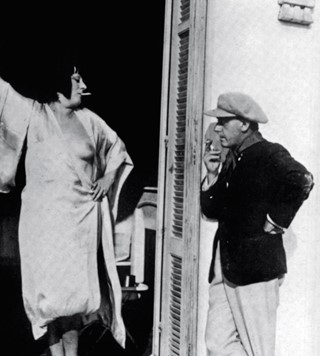

Drawing on the building’s history as a Victorian Chapel, it follows a version of the work in New York last year at Church of the Village, and is the occasion of McDermott and McGough’s first show in London. Beginning their collaboration in 1980, faithful to late 19th and early 20th-century techniques, the duo have realised a body of work exploring time, their identity, performance and the art of living. (Sidenote: it’s perfectly apt or not at all that McDermott was born in Hollywood, 1952, as the curtain drew on its golden era).

Tributing Wilde as an icon and addressing both historic and enduring inequality experienced by the LGBTQ+ community, the temple is available for ceremonies, marriages and meetings, with all proceeds from private events, as well as public donations, supporting The Albert Kennedy Trust, a charity for LGBTQ+ youth at risk of homelessness. It will also host a programme of events.

Peter McGough met Another Man at the space to talk controversy, community and green carnations.

The Oscar Wilde Temple addresses – and redresses – history. Not many figures go from jail to having their own temple. Can you tell us about the project?

Peter McGough: Well, [David] McDermott wanted to start a religion 25 years ago. I had this book, The Oscar Wilde File, which had a green carnation on the cover; an ugly, cheap book that had imagery from the press of the day of him being arrested. We began talking about The Oscar Wilde Temple and kind of forgot about it until the [same sex] Marriage Act passed in Ireland, and in America under Obama. I saw outside my apartment window the Stonewall Inn being landmarked by Cuomo, performing a ceremony with a same-sex couple.

I’d met Alison Gingeras, [François] Pinault’s curator, who was a curator at the Pompidou and I called her up and told her our idea – she was, like, ‘Oh my god, this is so good.’ We went about it but it was cancelled in Europe because some local had felt we were making fun of the Catholic church. Alison said: ‘Let’s not forget about this, I don’t want it to die.’

“This is a place where people can find solace and comfort. I want people to get married because what same-sex couple doesn’t want to get married under the deity of Oscar Wilde?”

So she contacted [film producer] Dorothy Berwin, and Dorothy Berwin brought it to the LGBT Centre [in New York]. I said, ‘If we’re going to do it there, I want LGBT homeless youth to participate in the funds we raise.’ We did it with the church across the street that had the first Parents and Friends of Gays and Lesbians that a mother had started. It was fantastic. Then Alison suggested it to Joe [Scotland], Studio Voltaire’s director and he said yes. They went above and beyond, I am so thrilled what it looks like.

They’ve borrowed these paintings of ours – Queer which we painted in 1986; Cocksucker; and A Friend of Dorothy. Alison said these words were very radical for the time. Queer is such a hateful word and I think we were at the beginning of changing it. Now it’s Queer Cinema and Queer History, so I’m kind of taking some credit – I was there and I did it. Because I was just sick of it.

Given the history, it must feel important that you brought this to London?

Peter McGough: Yes – Clapham Junction train station was where Wilde was harassed and spit upon. He was witty but the crowd wanted him dead. I thought of all the things that are happening like Black Lives Matter, the #MeToo Movement and I had to do something. You know, I marched. This is a place where people can find solace and comfort. I want people to get married because what same-sex couple doesn’t want to get married under the deity of Oscar Wilde? Every religion I’ve studied says ‘Sorry, no gays or lesbians or trans [people]’ so I thought ‘why not start your own?’ – can’t we all just get along? The great quote of Oscar Wilde is: ‘Be yourself, everyone else is taken’. That’s an incredible thing to tell these kids who are wanting to be like some pop star. We painted a portrait of Oscar Wilde in the 70s and gave it to Glenn O’Brien, he had it for years.

You’ve collected a gallery of martyrs for the temple…

Peter McGough: I thought of Harvey Milk and I thought of Marsha P Johnson, who I could talk to on Christopher Street when I was a teenager. She was always there. Our work has always been political, always. I made a place for LGBTQ+ people to find solace: gays and their admirers. Someone in The Times wrote, ‘It’s all for the homosexual; what about us?’ I just wanted to say you’ve ruled the world. I’m the one who’s been running from gangs my whole life, being called a faggot. I’ve been spit on. I’ve been beaten. I’ve had bottles thrown at me from passing cars screaming at me, and McDermott worse. Just give me a fucking break. I knew Quentin Crisp – he marched out with make-up and orange hair in the 40s and would pick up American sailors. He was beaten and all sorts.

“Someone in The Times wrote, ‘It’s all for the homosexual; what about us?’ I just wanted to say you’ve ruled the world. I’m the one who’s been running from gangs my whole life, being called a faggot” – Peter McGough

Tell us about the Gesamtkunstwerk in which you and McDermott lived.

Peter McGough: When I met McDermott he was living in the past. I understood the past from my father’s 1940s clothes and old movies. When we moved into this house on Avenue C he tore out the electric and he threw out the radiators, so we lived by fireplaces and candlelight. Luckily, we had a 1900s bathroom he didn’t tear out and the stove in the kitchen below was an 1880s little gas range. It was an artwork – McDermott is a great, great installation artist and he brought that into the work. He couldn’t use Philips head screws, there could be no plastic, there could be no radio, no computer, no air conditioning – so when it was 99 degrees outside, it was 99 degrees inside. After the crash of the late 80s, we lost everything. We didn’t save a penny. I think that it was a performance art piece of the highest order. There are a lot of kids now who are old fashioned, especially in New York, but they have computers, they’re on their cellphones constantly. I got a computer in 2006 when I hired a studio manager – they said, ‘I can’t work for you unless you get a computer.’ McDermott is the only person I know who doesn’t have a computer or cellphone. He calls cellphones your ‘pocket robot friend’.

You’re wearing a green carnation on your lapel. I’ve never seen a real one before.

Peter McGough: You can find them in Korean delis in New York. Or little delis, but very rarely. The book [Robert Hichens] wrote mocking Oscar Wilde is called The Green Carnation. And Noel Coward wrote a divine song called (We All Wear A) Green Carnation, which is hysterical, so witty. They’re so wonderful. Some people think it’s for St Paddy’s day but the ones who know know – I’m like, ‘I know you know, girl’.

The Oscar Wilde Temple runs until 31st March 2019 at Studio Voltaire, 1A Nelsons Row London, SW4 7JR; www.oscarwildetemple.org