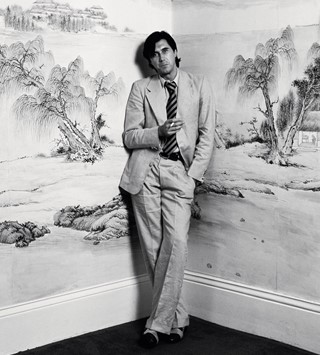

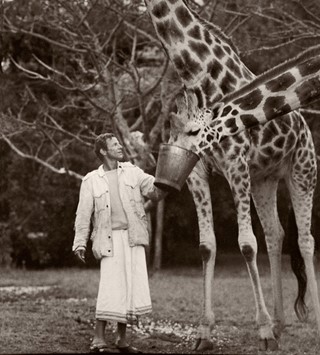

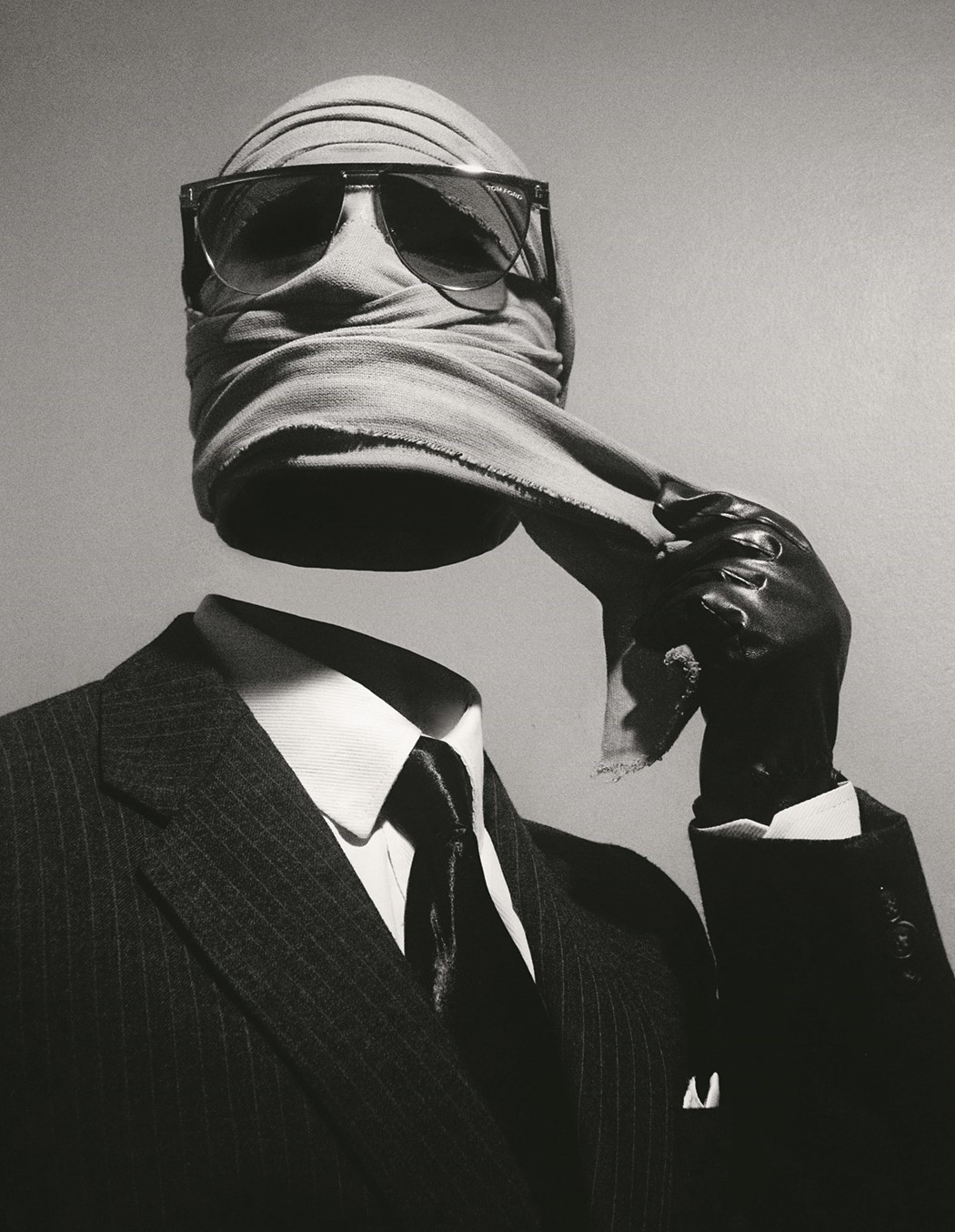

Christopher Smith, the Artist Creating Instagram’s Most Electrifying Images

- TextTim Blanks

- PhotographyChristopher Smith

From his tiny bedroom in Port Elizabeth, Christopher Smith conjures some of the most spellbinding images on Instagram. Here, the gifted young artist creates an exclusive new series for Another Man

Taken from the S/S18 issue of Another Man:

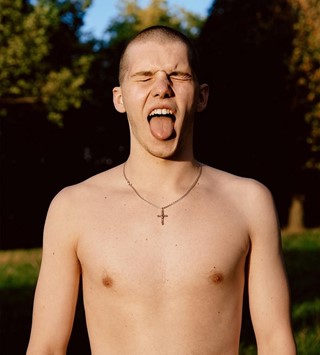

Christopher Smith is 22 years old. A first generation South African, he lives in Port Elizabeth, a small coastal city on SA’s Eastern Cape, with his mother, an older brother and a younger sister. His father, originally from Leeds, passed away in 2016. Port Elizabeth is a typical Southern Hemisphere gem: sunshine, surf and sailboats. Though Smith is no beachgoer – he insists he looks like a ghost lying in the sand – he loves his hometown. He’s comfortable with the isolation. “Life in the slow lane is perfect for me,” he says. He’s 5ft 7in, he’s studying graphic design. He calls himself “a plain Jane”. The biography is testament to what he insists is his profound ordinariness. But Christopher Smith is about as ordinary as Einstein.

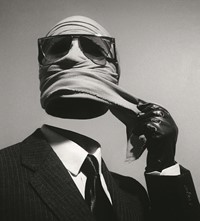

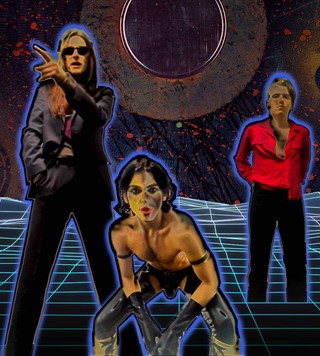

He posts pictures of himself on Instagram as @mechrissmith, around 120 images since he created his profile two years ago. He claims he’s not trying to generate any kind of mystique: “I don’t think I’m that interesting beyond the images.” A provocative statement given that his pictures reflect the complex inner life of a human chameleon, as chic as a fin de siècle grande dame one moment, as stark as a bloodied, brutalised boxer the next, or as horrifying as a flayed corpse. The seesaw between studied elegance and sadistic violence has made Smith’s page a consistently disturbing destination for fashion’s cognoscenti. And every last glamorous or ghastly image is him.

His first post was March 2016. An unvarnished self-portrait, the ground zero for what was to come. This is me, Christopher Smith. It coincided with his coming out. “That’s one reason I got into Instagram. It wasn’t a secret before. But once I’d come to terms with myself, I felt more comfortable sharing publicly. I didn’t care what other people thought.” Not that he’d want to be held up as a figurehead of fabulosity for conflicted young men and women around the world, but his coming out underscores the sense of release in his pictures, the excitement of new frontiers.

Smith had been taking pictures of himself on his phone since he was 16. Even then, they were mini-productions, with backdrops. “I felt like a little movie director,” he says. His earliest obsessions were The Empire Strikes Back and Halloween. “Those were the things that got me interested in fantasy. I was so fascinated with how they were made.” And making images in their spirit had nothing to do with selfie narcissism. “I’m the least interesting person I know,” Smith insists. (The self-deprecation is a constant thrum.) He became the star of his own show because there was no one else forthcoming.

“My images are completely 110 per cent staged, formal, everything deliberate. No imagining the moment before or after. People might say that’s so old-fashioned but they’re the pictures I like. I look at the 1920s and 1930s as so far away from my time that it’s pure fantasy. The reality of now doesn’t interest me that much” – Christopher Smith

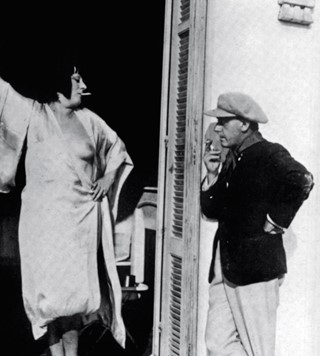

He got a “proper” camera when he was 17, a little compact digital Samsung, which he’s been using ever since, with a tripod that belonged to his father. “That was when I started getting interested in the photographic process. I started looking at image-makers.” That was how Smith came to fashion, the genre of image-making that was most concerned with the formal elements he was drawn to: line, shape, texture, colour. He began looking at Vogue. “UK, US, French, I didn’t know the difference, I just knew they were the standard. And they’d have looking-back articles with a photo by Horst or Hoyningen-Huene. I’d wonder who they were and look them up in the university library, which had everything. That opened up my mind even more, and after that it was much less about magazines and more about what was out there, looking at archives on the internet, looking at album covers, news photos, autopsies.”

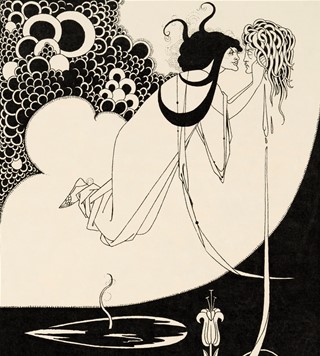

Smith says Horst is still his favourite, each classically composed chiaroscuro image its own little dreamscape. “My technique is totally inspired by fashion imagery. I always think there’s a slickness, a bit of a polish to every image I do.” He never thinks of them as stills, frozen moments from a sequence, like Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’. “No, mine are completely 110 per cent staged, formal, everything deliberate. No imagining the moment before or after. People might say that’s so old-fashioned but they’re the pictures I like. I look at the 1920s and 1930s as so far away from my time that it’s pure fantasy. The reality of now doesn’t interest me that much.” And yet, he says, “My life in a nutshell is me sat on my couch with my computer looking at images online, with either CNN or VH-1 music videos on in the background. That’s where I get everything from.” It’s this clash between Smith’s perceived purity of the past and the chaos of the present that contributes to the unsettling tension in the pictures he makes. And it’s mirrored in his rough and ready process.

“Every image I have in my head beforehand,” he says. “I always have the final image in mind. Maybe that’s part of the graphic design mindset. I always think about the entirety.” Smith claims he never takes much more than an hour per image, with maybe another 20 minutes beforehand to create the look. Take the headless torso, for instance. A black stocking on the head, fabric paint on the neck. Quick, maybe 20 minutes from initial conception to final execution.

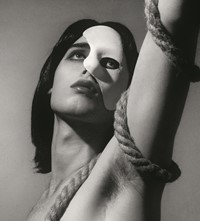

“I try to do the cheapest, simplest thing possible, and if I can’t do it, I move on. My bedroom is tiny. I have three places to shoot – on my bed, next to the shelf if I’m using daylight, or next to the bed if I’m doing a nighttime picture with my reading light.” The floor is usually covered with books, which Smith has to pile on the bed when he’s taking pictures. (He was hoping for a bookcase for Christmas.) His family, elsewhere in the house while he’s working, is supportive but never involved. “I don’t want their help, I’m too self-conscious,” he says. “I don’t like being photographed at all. Or for people to see me posing like an idiot, even though I know it will turn out right.” In one of Smith’s most shocking images, he is dangling from a noose, lynched. The logistics of creating such a scenario made him consider assistance. “I wasn’t sure how to get the rope right so I asked my sister if she could hold it. She said, ‘No, I’m studying’.”

“My bedroom is tiny. I have three places to shoot – on my bed, next to the shelf if I’m using daylight, or next to the bed if I’m doing a nighttime picture with my reading light” – Christopher Smith

He claims his room looks so ridiculous that no one would believe the conditions in which he makes his pictures. “I feel so stupid, lying on my bed, paper on the wall, doing these poses. It’s so low-tech and boring.” But then I think about the photographers he reveres, the pioneers of the medium like Nadar, Frederick Holland Day, Edward Steichen, achieving their effects with the most minimal resources. It was all about the thrill of looking, the weird charge in being able to show people things they’d never seen: “This is what I see and now you can see it too.” Smith feels something similar. “It’s almost like a naivety, a direct simplicity. That’s the thing I like most. It must be direct. I love Beaton, and even with all his ridiculous props, there’s a directness.”

Maybe that’s why the gruesomeness of the lynching, the decapitation, the gouging, the hammer in the eye is closer to the bone in Smith’s work than mere Grand Guignol. So grotesque that they make you wish Instagram’s response mechanism was more nuanced. “Like” scarcely seems adequate – or appropriate. “I know when people see them, they wonder what sick things are going on in this mind,” he acknowledges. “But my inspirations are random. My mother loved true crime books. When I was seven or eight, the pictures in them gave me nightmares. Like the covers on the boxes in the video shop. I love being scared. So all those images – the hammer, the decapitation, the lynching – they’re me wondering what it would be like to go through that. It’s not sick fascination, it’s more fear.” At first he resists the notion that confronting his fears in such a way is some kind of exorcism, but then he comes round to agreeing that it may be so. “I feel like once I recreate it, I’m immune to being scared by it. I’ve moved on from that idea. Once the image is there, the idea of having my eyes gouged out doesn’t shock me personally.”

I think it’s odd that someone who is so obsessed with fear claims he has never really thought about his own greatest dread. “A physically painful death?” he muses. “But it seems really far away from me. It’s the same as dressing as a woman. It all fits in a fantasy. I’m thinking about a way of dying I can’t even comprehend. The hammer in the eyes is not everyday.” Never mind that the vast majority of people wouldn’t even let such thoughts in. But fantasy for Smith is a strange and broad church. “It’s the unifying factor between the beauty and the darkness,” he says. “It’s all fantasy – the Horst pictures, the autopsy pictures, all fantasy. So far away from me and my life. That’s the unity for me. If I go from a pretty picture to violence, I’m not thinking, ‘Oh, I’m changing.’”

And, in that, Christopher Smith believes he is old-fashioned. “For me, there must always be an element that brings it back to an era or a time in the world.” If equivalence is a toxic notion in our charged cultural climate, his faith in the primacy of the stand-alone, context-less image is his salvation. “And it is image-making, not self-portraiture,” he insists. “I don’t look at the pictures as me at all. It’s totally separate. I’m just a person standing in. The further I can get away from me with makeup or whatever, the better. It’s nothing for me to wear a dress, it’s just, ‘How would I take a photo of a society woman?’ I imagine myself as that image and create it.”

“I don’t look at the pictures as me at all. It’s totally separate. I’m just a person standing in. The further I can get away from me with makeup or whatever, the better. It’s nothing for me to wear a dress, it’s just, ‘How would I take a photo of a society woman?’ I imagine myself as that image and create it” – Christopher Smith

There’s an inevitable analogy in the work of Cindy Sherman, finding a thousand other creatures in herself, everything from Hollywood beauty to utter depravity in an enormous, forensic analysis of the self. “I found out about her later,” Smith says. “She seemed to be much more self-consciously exploring identity whereas for me it’s much more…” he pauses, searching for les mots justes, “…not trying to make any big statement. Every image reflects what’s interesting me at the moment. I love Cindy Sherman’s work, it’s genius, but I’m only doing self-portraits incidentally.”

So go to @mechrissmith, wonder at what you see. No politics, no hidden agenda. Just a boy in his bedroom in a faraway town exalting in his ability to become absolutely anyone or anything. And everyone who visits wishes they could be that free.