From IT to Ink, these anti-establishment publications made way for a new era in press

- TextBelle Hutton

“It’s the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love,” say Barry Miles and James Birch, curators of new exhibition, The British Underground Press of the Sixties. “We wanted to show that dissent was possible and to encourage young people to fight back against Brexit and Trump, for example – to show that you can do it outside the system.”

The duo’s exhibition, which is on show now at London’s A22 Gallery, brings together the most subversive publications of the decade, highlighting their power and resonance, and how they made way for a new era in press by offering the youth and countercultures of the 60s a platform and “challenging the status quo”. “It was a period when people felt very threatened by the political establishment in general and the British Underground press gave voice to an alternative opinion,” they explain.

Here, Miles and Birch take us through five of the period’s anti-establishment publications.

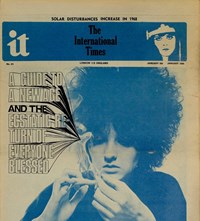

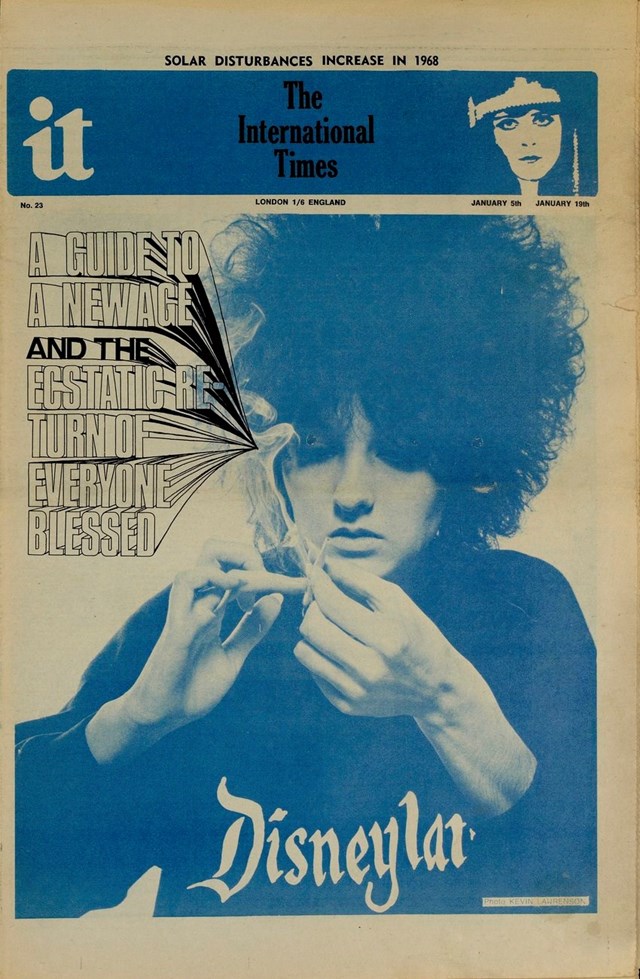

1. IT

International Times, or IT, “was designed as a vehicle for the various ideas of young people in the mid-60s”, explain Miles – who was one of the paper’s founding editors – and Birch. Notable was its scope: IT reported on “everyone from hamburger-eating Hell’s Angels to commune-living vegetarians in North Wales; from skin heads to the Notting Hill rock and roll scene”. With funding help from Paul McCartney and issues printed every two weeks, IT was Britain’s first underground newspaper following its launch in 1966. Focus was placed on the kinds of illicit subjects not highlighted in mainstream media: “it covered things like the price of pot on the street in Stockholm – and also sometimes warned of people who were suspected of being undercover agents. We weren’t trying to create a scene, we were reporting on the scene.”

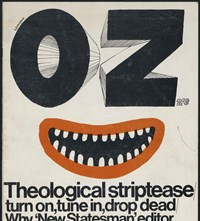

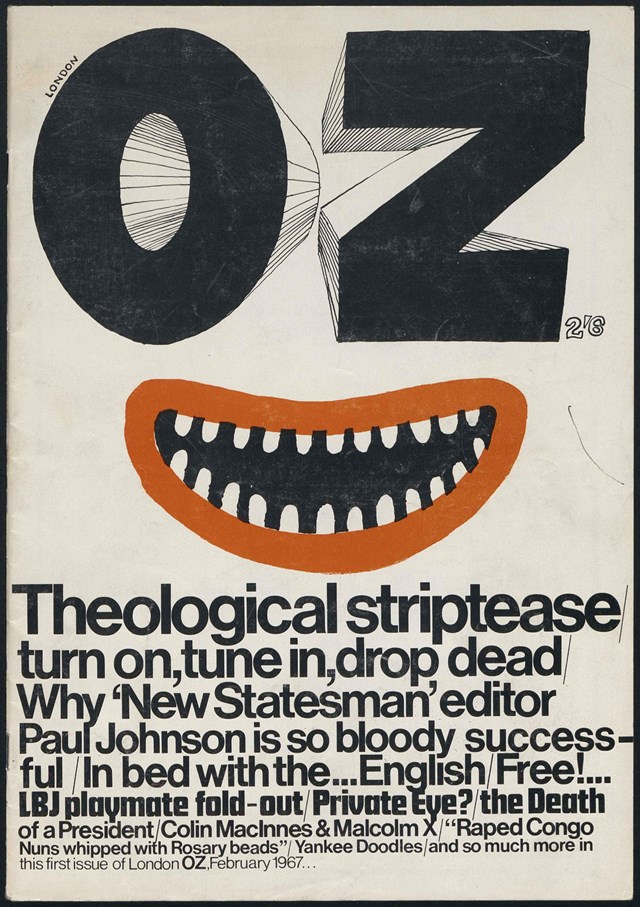

2. OZ

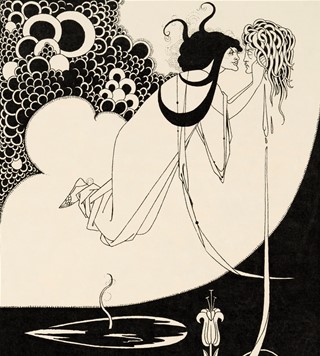

OZ is one of the period’s most notorious titles. Its issues were published monthly and comprised “articles and think pieces”, bound in psychedelic covers that became as infamous as its content. “Being a colour magazine, it became a vehicle for subversive and experimental graphics, both in subject and in printing experiments – overlays, washes, rainbows,” explain Miles and Birch. OZ spent its six years in circulation courting controversy by championing issues like women’s liberation and homosexuality, and was at the centre of Britain’s longest obscenity trial following the Schoolkids issue, which saw secondary school students edit the May 1970 edition.

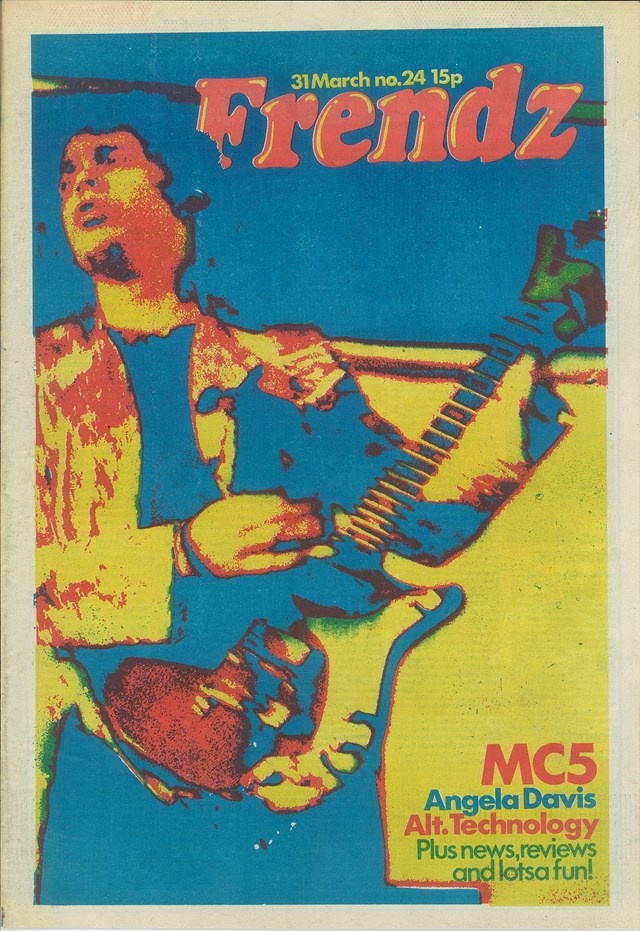

3. Friends/Frendz

What started out as Friends of Rolling Stone (since its staff comprised British Rolling Stone editors who had been fired) soon became just Friends, and was known as Frendz in its last incarnation. Friends’ stance leaned more towards “the countercultural lifestyle – interviews with celebrity filmmakers, actors, musicians”. It was when much of Friends’ staff travelled to Northern Ireland hoping to report on the political situation there that the publication’s last transformation began, as Miles and Birch explain: “They were immediately arrested and [editor] Alan Marcuson went over to bail them out. When he returned he found the magazine was now controlled by a women’s collective; his authoritarian editor’s desk was replaced by a round table which immediately collapsed when he leaned on it. Feeling he had no further role to play he took the financial records of Friends, threw them in the canal and told the staff that the magazine was theirs. Friends was in deep financial trouble so a new company was formed to avoid paying the printers, et cetera, called Frendz – run by a staff collective.”

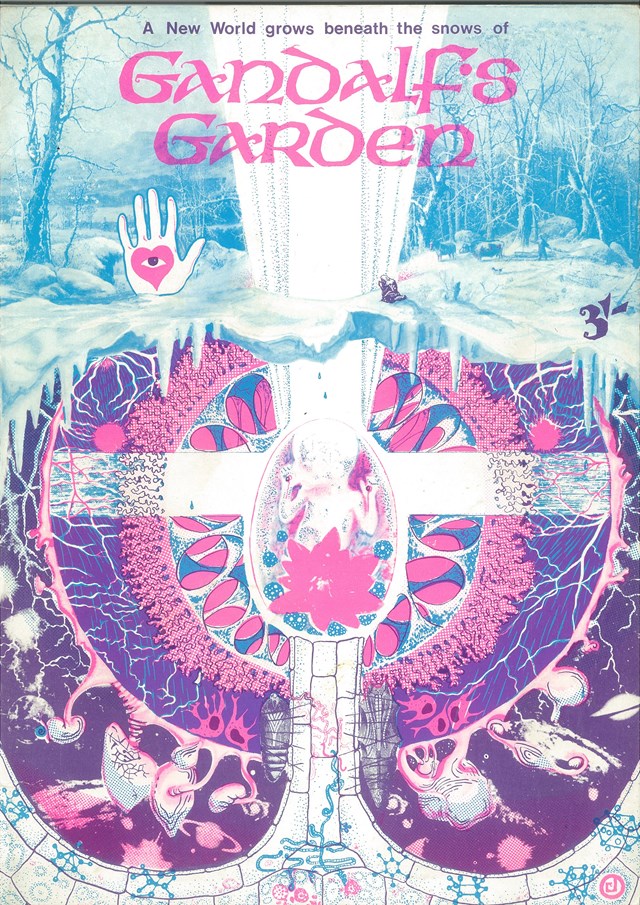

4. Gandalf’s Garden

“One aspect of counterculture [in the 60s] was an interest in Eastern religion and mysticism, and Gandalf’s Garden was the first British magazine in the period to cater to this,” say Miles and Birch. The magazine was, along with a shop in Chelsea, a by-product of the community named ‘Gandalf’s Garden’, set up by Muz Murray. Murray – now a Mantra Master – had “set up a meditation centre in Chelsea which also allowed indigent hippies to ‘crash’” and Gandalf’s Garden emerged in 1968 as a “mystical scene magazine to cater for the growing interest in all things eastern”. In much the same vein as Oz, Gandalf’s Garden was characterised by its singular and vivid graphics.

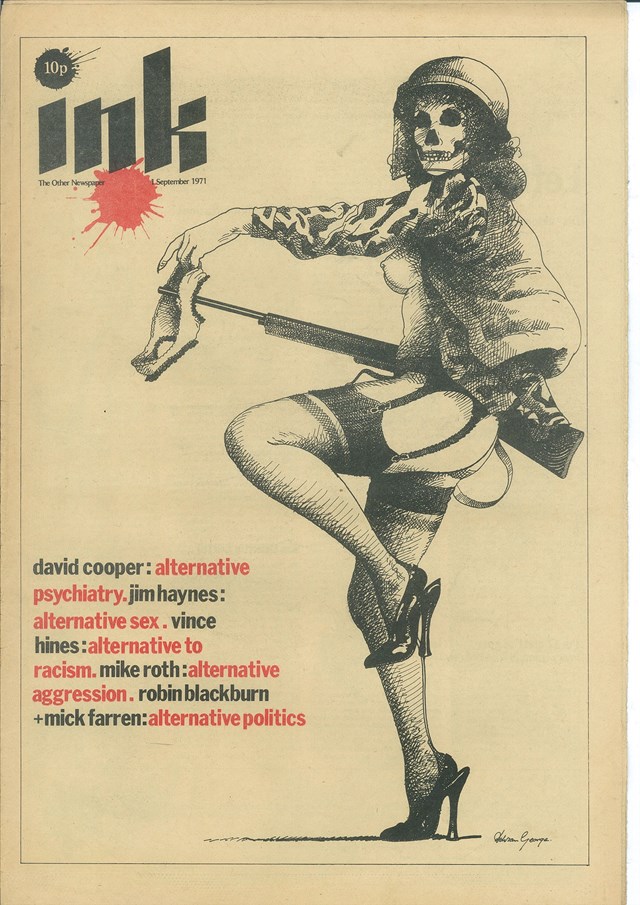

5. Ink

Ink was the brainchild of Richard Neville, Oz’s editor and publisher, and literary agent Ed Victor, and “attempted to bridge the gap between the hippies and the left-liberal intelligentsia of north London”. In what turned out to be a short-lived venture due to “under-financing and problems with the editorial team”, Ink billed itself as ‘the other newspaper’ and sought to appeal to a wider readership, beyond the underground counterculture, when it first printed in 1971.

The British Underground Press of the Sixties is at A22 Gallery, Clerkenwell, until November 4, 2017.