Karen Knorr and Olivier Richon’s images of anarchic punks in the 1970s are currently on show as part of a London exhibition. Here, Knorr shares the story behind her seminal series

- TextBelle Hutton

Karen Knorr was born in Germany to American parents and grew up in Puerto Rico, before studying in Paris and then moving to London. “Here I was, this Puerto Rican American, and I was trying to understand British culture,” says Knorr over the phone from Washington DC, though she has been based in London since the 1970s. “I did it through photography. That’s how I sort of figured it out.” Knorr credits her status as an “outsider” as being formative to her photographic practice, which has long been concerned with culture and society.

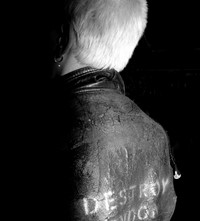

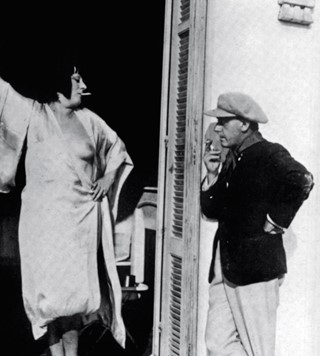

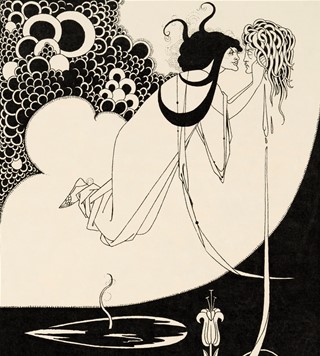

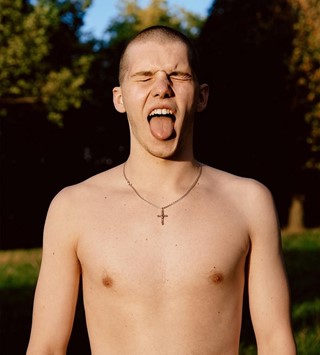

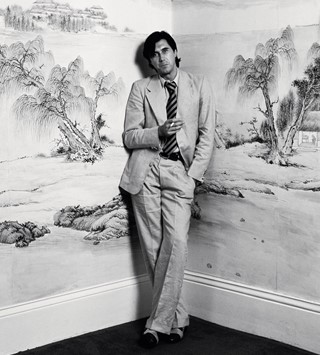

Knorr made some of her most enduring and seminal photographic series early in her career, in the 1970s and 80s, during which time she looked at different echelons of British society, and developed an idiosyncratic use of irony and satire in her photography. Two of Knorr’s series from this period, Punks, co-photographed with Olivier Richon, and Belgravia, are currently on show in London as part of New Order: Art, Product, Image 1976–1999, a group exhibition at Sprueth Magers. Curated by writer Michael Bracewell, who Knorr has known for 30 years, the exhibition examines identity, art, image and culture in Britain in the late 20th century. Knorr’s works embody a dichotomy in Britain at the time: riotous subcultures like the punks existing alongside the moneyed middle and upper classes we see in Belgravia, at a time of change as Margaret Thatcher came into power. Fittingly, Knorr decided on an “anarchic, non-linear” display for her and Richon’s Punks in New Order, while the photographs from Belgravia are neatly spaced on the gallery wall. Here, Knorr tells the story of Punks – the first photo series she ever made.

“I wasn’t just interested in photography as a technical tool. I wanted to think through photography in some way, I guess. I was doing a part-time course called ‘Professional Photography’ at Harrow College of Technology and Art. At that time, I was basically trying out different formats, learning how to develop, light an object, you know, things like that. I had already met Olivier Richon – we’d started doing the Punks because we’d go out clubbing, you know, checking out London, and we discovered this music, this subculture, and we just hung out with them. We then applied to a course at the Polytechnic of Central London, which is now called the University of Westminster, with a joint portfolio of Punks – and those Punks are the ones you see on the wall at Sprueth Magers. So this is our student work – our first body of work where we actually learned how to make photographs, and we were working with analogue photography, we were developing ourselves. One of us would hold the flash of the camera and the other one would hand-hold – you know, no tripods or anything – and photograph and then we would switch roles. So all of the images on the wall are co-authored.

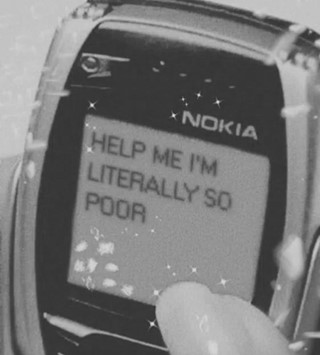

“The work was done over a period of three months, from January 1977 to March 1977, in several clubs like the Roxy, Global Village, the Vortex. We kept on going back and back – I mean we must’ve gone back about 20 times, at least. We weren’t really interested in the celebrities of punk, to be honest. We were more interested in ordinary people that would come from their suburban homes with their punk gear in a black plastic bag and transform themselves before going into the club. We were very impressed by the humour, by the sort of improvised montage of different things that they would bring into the clothes, and the DIY aspect... nothing was perfect, it was all improvised. They were absolutely performing for the camera. They loved it! It was really collaborative and performative in that way. We didn’t ask them to pose – they just went into their own poses. They performed for us.

“The other thing that attracted me, as a young woman, was the fact that so many of these punk musicians were women, and they were doing strong and quite aggressive lyrics that weren’t pretty songs, or you know, folk songs. There was a tradition in the music industry of women singing folk and that’s wonderful and I admire that, but what I found so interesting at that time was this very challenging punk music being sung by young women.

“Here I was, this Puerto Rican American, and I was trying to understand British culture. But then I did it through photography. That’s how I sort of figured it out, and how I felt about the inequality. There was inequality, very much so, and when I arrived, Britain still hadn’t modernised. Thatcher, as critical as one might be, modernised the country. She broke the unions, which was problematic and we’re still suffering from those gestures today, but nonetheless, she transformed British society into a home-owning society. In some ways, Britain’s modernised now, but in other ways, it’s still the same, which is rather extraordinary. I find it extraordinary, that at my age – I’m 65 now – people are still looking at my early work and finding ways of engaging with it.”

New Order: Art, Product, Image 1976–1999 is at Sprueth Magers, London, until September 14, 2019.