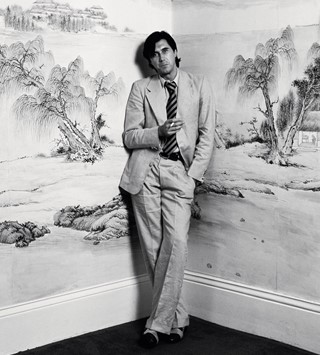

40 years after its initial release, director Ron Peck tells Another Man about the groundbreaking feature – and why it’s still resonant for queer people today

- TextBen Coopman

Queer life in 1970s London might bring to mind the first gay pride marches and heroes of the gay liberation movement, from Derek Jarman to Peter Tatchell, but if those things were happening during the time of Nighthawks, it’s on the periphery. In the world of Jim, a geography teacher from Reading, the revolution is only cautiously finding its feet.

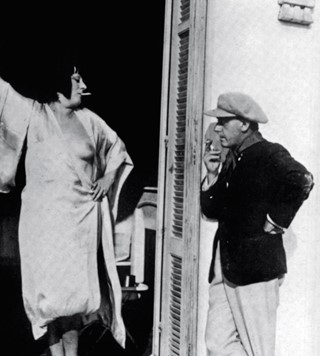

The first major British gay film, made by a young director named Ron Peck and released in 1978, was a community-driven response to the lack of LGBT representation in the media. The result is a panorama of the gay experience through the eyes of one man. By day, he teaches at a school in inner-city London, taken for straight by pupils and colleagues alike. By night, he searches for sex and love in a subculture on the cusp of change, moving through different worlds around the city, even if he doesn’t fully belong to any of them.

For millennials nostalgic for a time before Grindr and Barclays-sponsored pride parades, Nighthawks is a reality check. It’s an unflinching time capsule of a London that feels closed off and claustrophobic: of overcast skies, urban decay, traffic, white-bread sandwiches, Strongbows and cigarettes. In the cruising corridors and on the dancefloors, Jim joins the hunt on a seemingly unending search for connection, putting himself up for rejection by men who hold pints instead of phones.

But it’s also an important reminder of the small acts of courage that have paved the way for our world today. Despite the loneliness of existing between worlds, Jim never turns mean, gives up the hope of finding love, or pretends to be anyone he isn’t. At school, as rumours finally reach the classroom, he faces a barrage of questions from teenagers at their desks, from what he likes in bed to whether he fancies little boys. It’s a gripping and eerily familiar scene, but he calmly and patiently answers their questions and challenges their prejudice. He may not be an artist or an activist, but there’s something heroic about Jim.

Here, 40 years after its initial release, Another Man talks to Ron Peck about the landmark film, and why it’s still resonant today.

Ben Coopman: The film was released over 40 years ago now. How is it going down with audiences today?

Ron Peck: I’m amazed at the sudden upsurge in interest [in it]. I presented the film at a screening in London over the weekend and what surprised me was that the audience was almost all people in their early twenties. I think they’d been directed there by someone else who’d seen the film. It went down very well with them, so that was very refreshing.

Ben Coopman: What do you think is behind this interest among younger people?

Ron Peck: Someone at the screening said that it was different to any other film he’d seen before, so I think the aesthetics are what makes it different today, more than the content. The fact that, apart from the main character, it’s made with people who joined the workshop and were improvising. There’s a kind of naturalism to the surface of the film.

The film itself is structuralist in that it’s built on a repetitive rhythm, where this teacher meets one person after another, and you feel as you watch it that you want this rhythm to break. I think that was challenging to them in a way that they found interesting, not predictable.

Ben Coopman: How much do you think it resonates with the gay experience today?

Ron Peck: That’s hard for me to judge really. I think that it’s a reminder of a past, because I think young people today have a sense of entitlement which we didn’t have. It all had to be worked for [before]. Today, they’re able to be very open, which my generation generally wasn’t. So much has changed. I was realising that the film is equivalent for me in the 60s or 70s watching a film from 1928. So it’s incredibly old, but it doesn’t seem to be locked in the past. There are enough issues that resonate – the whole business of forming relationships, of being honest.

The film was shown not long ago in both Slovakia and Ukraine for the first time. The comments that came back to me were that it seemed to describe the world that they were in today – that was how it works for them, it wasn’t too historical for them.

Ben Coopman: Many queer people in the western world look back at the 1970s with a kind of nostalgia – as a more radical time, with a more underground culture, more sexual freedom maybe. How does that square with your own experience of the time?

Ron Peck: There was an element of that, there was some excitement in some ways, if that’s a strange thing to say. You quite enjoyed having another life that not everyone knew about.

At that time people weren’t fighting for gay marriage, adoption rights or anything like that, what a lot of people wanted was to be different, to be distinct, to have their own culture. There was always some kind of division, there were some people who wanted and concentrated on legislating to change the law and there were other people who wanted to overturn society altogether – the revolutionaries. Those two sides were always there.

Ben Coopman: It’s fair to say that Jim feels pretty suburban rather than revolutionary. He’s not the most radical of figures to represent that era.

Ron Peck: It seemed important to address the fact that there was such an absence of representing an ordinary gay character, and we always talked of him as a kind of everyman that most people could find some sort of representation with, and it seemed to work – it seemed to have stood the test of time in quite an amazing way, more than we could have imagined.

We felt it was important to show a typical character who didn’t live a life of extremes – I didn’t want him to be an artist or anything like that, I wanted him to be integrated into society, and the school seemed like such a strong idea because we had such an issue with sex education in schools – and it hasn’t gone away even now.

Ben Coopman: What message do you want younger gay viewers to take from Nighthawks?

Ron Peck: I was quite haunted by a remark at the 40th-anniversary screening at the Notting Hill Gate cinema – where it first opened – that people seemed to be kinder then. I think people do behave rather well towards each other in the film and they’re all trying to explore themselves and trying to begin relationships in every case and they’re all trying to move forward and there’s no one who’s thoroughly unpleasant.

We didn’t have a special message other than we felt that the shape of the film should make you feel like the teacher. It forces you to push space open for yourself and widen the walls of where you are, and I’d like to see more of that.

Ben Coopman: Do you think it will shake people out of that sense of entitlement that you mentioned?

Ron Peck: I hope people will be curious about other parts of the world, and be very aware of what a liberal society we have here isn’t repeated across the world – people are in intolerable situations, and it wasn’t so long ago that people were thrown off the tops of buildings in Syria.

So it’s a case of looking at films from other places – not just documentaries but films that have been made there, and I do think a lot of those films are getting here at festivals like BFI Flare. Exploring that about other cultures, and not being too self-satisfied that you’re happy here because you’ve got a gay marriage and you’ve got a child. There’s more out there that needs addressing and that needs to change.

Nighthawks was due to be shown as part of BFI Flare, which has been cancelled due to the Covid-19 outbreak. However, subscribers to BFI Player can watch the film online here