Modelling, Raving and Squatting: Vinca Petersen’s Diary of the 1990s

- TextJack Mills

Featuring Corinne Day photographs, flyers and letters, Vinca Petersen’s 2017 book Future Fantasy is an ode to the power of coming together. Just reprinted, the artist speaks to Jack Mills about this incredible and intimate project

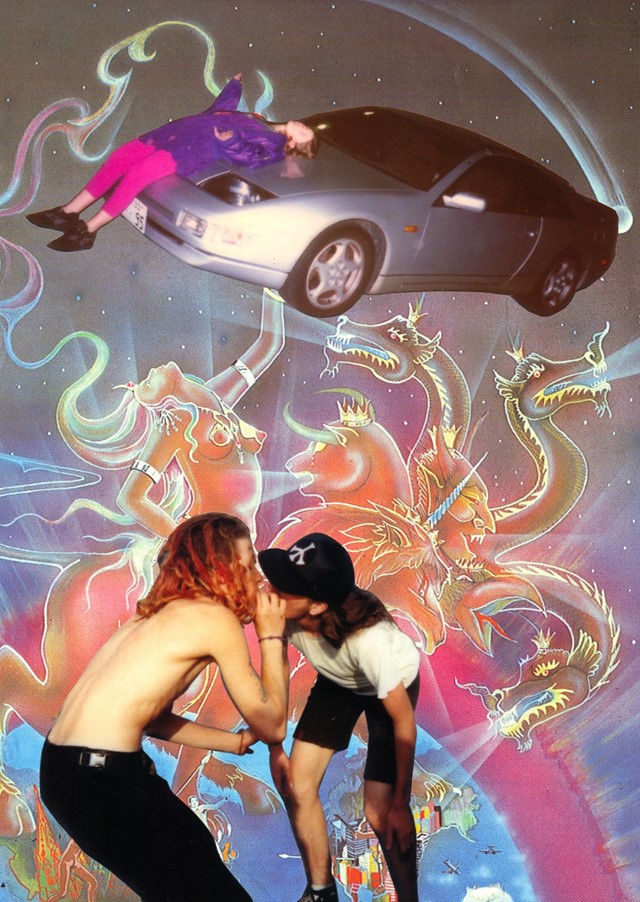

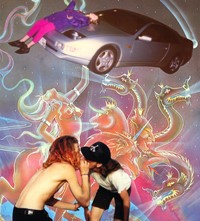

Written in the years either side of her 20th birthday, the diary of Vinca Petersen is a place where raving became something altogether more hallucinatory. In it, she writes about her times in transit; between her family home in Canterbury and the one she’d made among London’s squats; between the orbital raves of the M25 and the kitchens of 90s Britain. In among these scribbles, she slotted photos of her friends evaporating out of car windows, of fields flattened by feet, and of rare moments of quiet in the sodium glow of the sun.

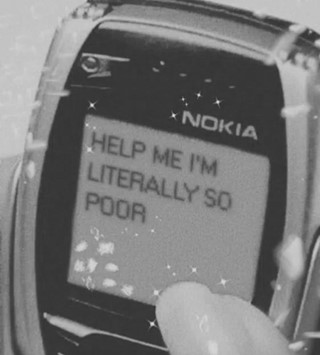

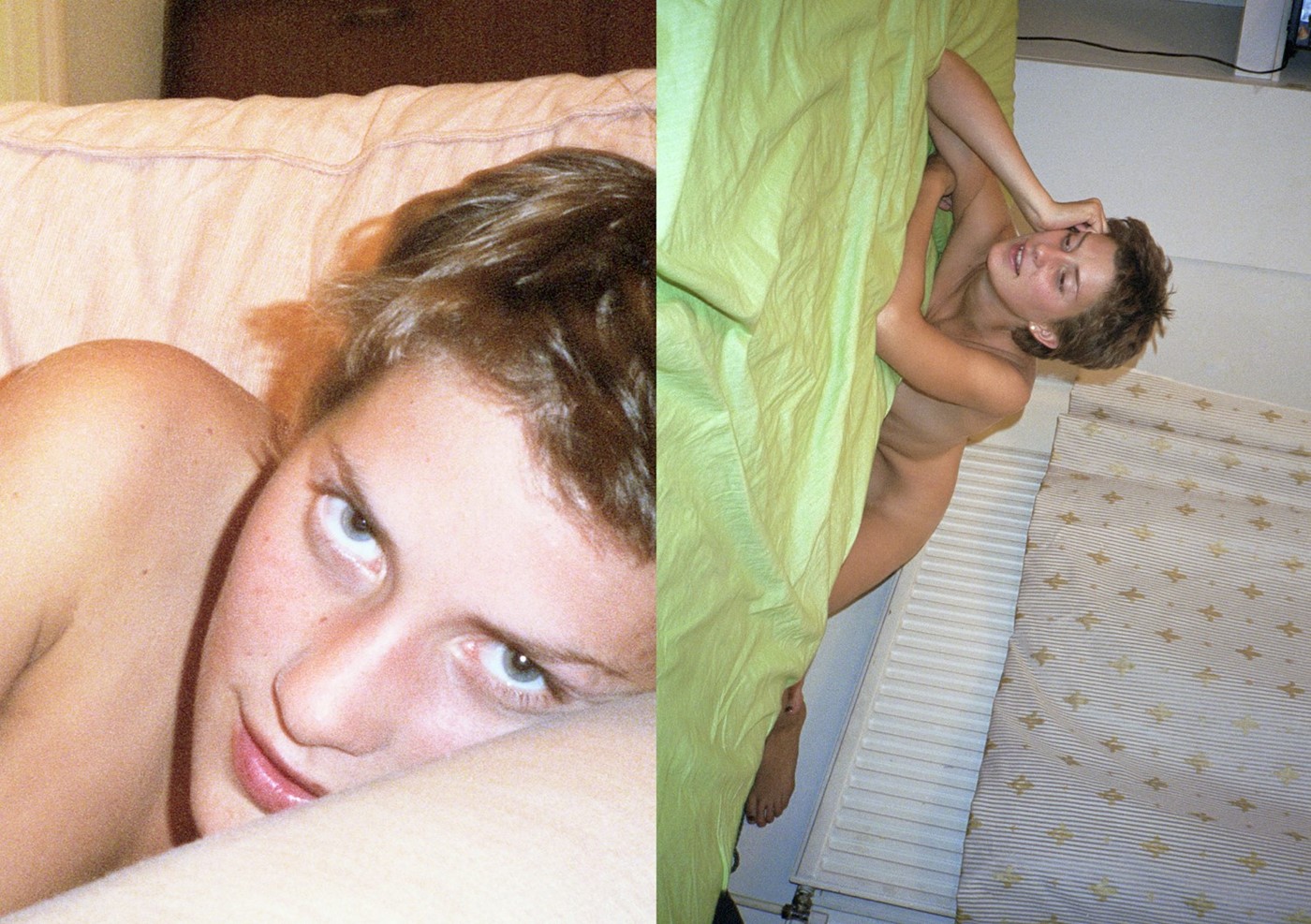

Nestled even deeper in the mire, halogen-lit rave flyers read like party political broadcasts. “Every weekend, and occasionally weekdays, someone, somewhere, for no immediate financial gain, puts on a free party,” reads one. “For those who will change,” warns another. Before the 1994 Criminal Justice Act put an end to illegal outdoor parties across the UK, Petersen had been supplementing her high-octane rave and ecstasy outings with modelling jobs, and crashing to earth in the Soho flat of the now sadly passed photographer, Corinne Day. Often, plainly beautiful nudes of Petersen taken by Day would end up in the diary. After the bill was past, she closed this particular chapter of it, and followed the sound systems to Europe.

Not so long ago, Petersen teamed up with art director Ben Ditto to turn these diaries into an object. Future Fantasy, the book, isn’t just a window into a freer UK, but a statement about the power fun can have over the collective psyche. If we could join arms then, Petersen seems to say, we can now. As the book is reprinted for a second edition this month, published by Ditto once more, she’s here to remind us how.

Jack Mills: Hi Vinca. What does Future Fantasy mean?

Vinca Petersen: There’s a specific era documented in Future Fantasy. When I was at school in Canterbury, I felt slightly at odds with education. I wasn’t a great rebel, but I was just never comfortable. I met a boy who had dreadlocks and these tight punk jeans that had tinned spaghetti printed on them. I would go [to London] on a Friday afternoon, spend the weekend with him, take an acid tab and wander around. I was from a fairly old-fashioned family where education was very high on the agenda – it was how you got anywhere in life. I remember having an interview at school with my mum, and [my boyfriend] was trying to explain to the headteacher why I needed to leave. I went up to London and there was something called The Squatters’ Handbook, it was like a zine that told you how to get a squat. We broke into an empty house, posted ourselves a letter and put a notice up that you’ve squatted and therefore had a minimum of a month before the authorities could chuck you out.

JM: The book doesn’t follow a linear storyline, like the one you’ve just described.

VP: No System [Petersen’s first picture-book, which documents her rave trails across Europe] captured a very intense world, one I lived in for a very long time. With Future Fantasy, I wanted to take away the feeling of it being extraordinary, to make it feel slightly ordinary so that anyone could relate to it, that they could even be their photos from their era, or photos they’re taking now.

JM: Do you have any favourite images in it?

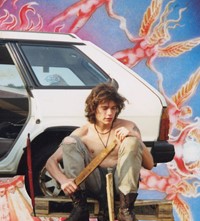

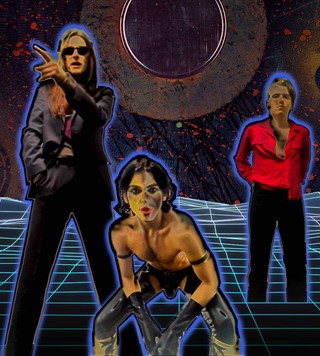

VP: There’s one of a man drumming with a stick, outside a car. He was my friend Johnny, my hero at the time. I was very young and we were at Reading Festival together. I felt like I was living in a film. Hilariously, the one of me dressed as superwoman or superman, it just makes me laugh because it was actually super dark. I was really young and this older guy, the only person I knew who had a decent camera, was like come to mine, I’ll take some modelling shots for you. So me and a friend spent a day creating ridiculous photos of us being as unsexy as we possibly could. It was so creepy; it’s just a brilliant modelling failure and I love it. On the raving front, the image of all the kids in the car stands out. Sometimes you’d be in a car for days, you’d go out and dance for the night, but you’d be in a car sleeping, coming up, coming down, sweating it out in the sun.

“With Future Fantasy, I wanted to take away the feeling of [rave] being extraordinary, to make it feel slightly ordinary so that anyone could relate to it, that they could even be their photos from their era, or photos they’re taking now”

JM: The UK you picture in the book looks and feels, philosophically, like a drawing; a fantasy.

VP: Future Fantasy is basically me leaving school: it’s about the choices you make at that point in your life. Back then, you could leave earlier, at 16. I tried to do one term of A-levels and couldn’t bear it and left. I think I’d just turned 17. You could see [what I did] as going off the rails, or as a descent into some sort of chaos – leaving home, going to live in a squat in London, getting really into the rave scene – but I always managed to keep it together. It was about the opportunities I had in front of me: I had the chance to go and live in a squat in the middle of the capital city rent-free, and that informed all of my other choices. I thought raving was fantastic, so I would do that for three days a week: leave work on a Friday afternoon and stumble in on a Monday morning. I found a job that enabled me to do that, which was modelling. I don’t know how I got into it in the first place – I was actually really unphotogenic. About one in 20 [editors] would book me because I was fun, and they knew they were going to have a good day.

JM: Do you think that’s a reflection on how the fashion industry has changed to reflect its responsibilities?

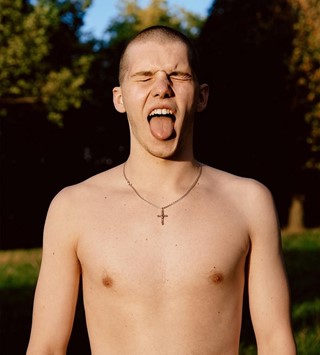

VP: Definitely. [The rave aesthetic] was completely non-commercial – that kind of look, the shaved heads and androgyny. [But the fashion world’s] sense of beauty now is fantastic, I love looking through magazines and seeing interesting faces, rather than purely photogenic ones. What I see in Future Fantasy is a young woman who probably had more opportunities than young people have today: not living in fear and just going out and making creative choices. An 18-year-old might look at the book today, or even someone in their 30s, and feel inspired. Currently, I’m having what I call “serious conversations about over-seriousness”. The idea that nothing is of value unless it’s serious is terrible, really. There's so much that has been drained out of our culture – really obvious things like village and harvest festivals, [where] you'd go into your local square and do this strange thing called dancing. For thousands of years, dancing has been incredibly important, and now we’re like, why do we need this wild and reactive social engagement of flinging yourself around? With Future Fantasy and No System, I was drawing people into another world I guess, opening people up to the same sense of adventure. The thread through both books is a sense of joy. Not the kind of sugary, commodified joy we get pedalled now, a subversive joy that isn’t for sale.

“[Corinne Day] was always a comfort for me. If I was ever in London, she’d feed me and we’d sit for hours smoking and drinking cups of tea on her famous sofa at Brewer Street, Soho”

JM: I think it’s interesting how you talk about festivals, where you’re forced to spend a lot of money to enjoy a feeling of community, and to explore people’s creativity – these are aspects of the human experience that are intangible and can’t really be monetised.

VP: Given a choice, you’d do it all for nothing, but spending money is the only choice we have now. Future Fantasy is the era just before the Criminal Justice Bill was enforced [in 1994], which made it illegal to put on [outdoor] raves. They tried to go underground in Britain, but it’s a small place and heavily policed, so the sound systems were driven abroad. The last picture in Future Fantasy is me getting in my truck. I’d moved home for a year, after squatting in London, before I bought a van and drove out to Europe. I came back to England permanently in 2004 having driven across Africa, and I remember noticing how many festivals [had started]. I thought, thank God the younger generation will be able to taste this because it’s so important to gather, to be frank, to be silly, to play. Connectivity and downtime from the pressures of work are incredibly important for your mental health. Glastonbury in the beginning was free for travellers. We used to dig holes and get under the fence, and I remember one guy who would charge a fiver to use his rope ladder. Now, there is a minimum of two lines of fence and they’ve got watchtowers every 100 metres. It’s bizarre, it isn’t just a village dance anymore. I’m getting goosebumps talking about it, because it’s dark.

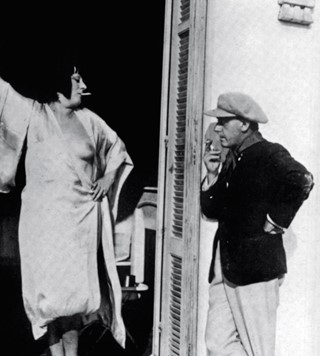

JM: Tell me about your relationship with Corinne: how it began and developed, and how it is reflected in these images.

VP: I had met Corinne a number of times, she wasn’t a great friend of mine initially. She was very interested in what I was doing, my way of life. She was always a comfort for me, whenever I came back to England. If I was ever in London, she’d feed me and we’d sit for hours smoking and drinking cups of tea on her famous sofa at Brewer Street, Soho. I met her when her boyfriend Mark Szaszy was making a video to go with the Radiohead song Creep for MTV; it wasn’t the official music video. There was a woman around doing the styling, she’d dress and chat to me, and that was Corinne. I was really friends with Mark first, so I’d go round to see him, but more often than not she’d be the one I’d end up sat on the sofa chatting with. People continuously asked me for photos, so I’d just make one for each sound system and go back out to Europe. It was too expensive to keep copying photos for everyone, so Corinne suggested I publish them properly. As far as Future Fantasy was concerned, there are pictures in it that she took of me. I wasn’t really her type; I was rather healthy looking and a little chubby for a model. There was a duality in my life, between living in a squat or driving to Europe in the summer, which I did before I lived on the road full time.

JM: What made you want to compile this period into a picture book?

VP: It was more about producing an experience than an object, and I want to share that experience with as many people as possible. The more copies there are out there and the more people have it, the better.

Buy a copy of the second edition of Future Fantasy by Vinca Petersen here.