A slew of designers rejected London Fashion Week Men’s usual theatrics for quietly beautiful clothing which focussed on craft and telling stories

- TextJack Moss

A frenetic, playful energy has come to define London Fashion Week Men’s, where theatrical runway shows and noise-making collections are de rigueur. It makes for a bright flash of ideas: far and away from the staid, hyper-luxury of Milan, or the vast international behemoths of Paris, London is rowdy and creative, with the volume turned up to 10.

And yet, this season, the suggestion of an entirely new mood: one of quiet beauty, where a slew of young designers eschewed the weekend’s usual theatrics for carefully considered clothing, with a focus on craft.

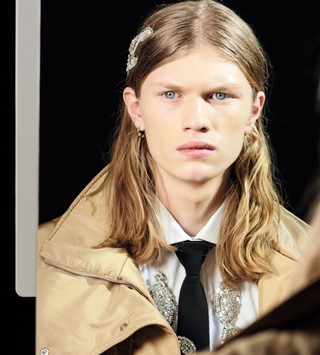

Or maybe not entirely new: one designer who has long championed the simple spectacle of clothing as clothing – the Daily Mail-denigrated ‘plank’ headpieces of his first runway collection perhaps withstanding – is Craig Green, a graduate of incubators Fashion East and the British Fashion Council’s NEWGEN. Attendees of Green’s shows will likely be struck by the soaring soundtracks, but in his often-sparse showspaces it is the clothing itself which burrows in the mind: this season, the intricate yet light-as-air series of closing looks inspired by Mexican Easter flags.

Granted, those particular looks might not be the ones worn by the average man on the street, but Green’s work is continually driven by consideration and restraint, where each item has been drilled down from layer-upon-layer of references: a YouTube tutorial for folding shirts by clean-queen Marie Kondo, human skin and Egyptian burial rituals were all mentioned by the designer this season. In his compelling collections these ideas are often channelled through the simplest of garments – the workwear jacket, the short-sleeved shirt, jeans. He makes the ordinary extraordinary.

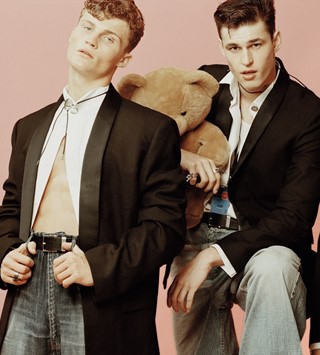

That could well, too, be the tagline for Stefan Cooke, run by the eponymous designer and his partner Jake Burt. Cooke is an ex-intern and fit model of Green’s, and has appeared in his shows. Cooke and Burt seem to lead London’s new guard: their recent S/S20 collection garnered rave reviews from Vogue and the Financial Times. “[Cooke’s clothes] are unique, and feel special and provocatively different to anything else around there,” said the latter’s Alexander Fury. “Which is particularly remarkable when what Cooke often does is take something normal, or familiar, and twist it.”

Memorably, the duo stitched thousands of buttons by hand to create Argyle vests for their S/S19 collection: from afar, they might have been made simply from cotton or wool. This season marked their first solo collection since graduating from Fashion East/MAN, and they found their inspiration from NYU college kids they saw hanging around the Village on a recent visit to New York. They noted their “ornate casualness” – in the collection, sweatpants were worn with intricately wrought lace-up shirts, inspired by 17th-century costume.

It is easy to miss the details: Cooke and Burt could likely talk for hours about the fineries of the craft which make up their collection, which at times has the intricacies of a couture atelier, but in a way it hardly matters. The end result is simply quietly beautiful clothing – a perfect, cocooning lemon yellow jacket, a trompe l’oeil deconstructed shirt, shoulder bags with threaded-bead handles – with a level of craft which means they cannot be replicated. You won’t find any of this on the high street any time soon.

The same is true for numerous other designers who showed over the weekend. Forget the Halloween horror masks, Paria Farzaneh’s collection, at a brief 20 looks, was full of blink-and-you’ll-miss-it subtleties: a patchwork mackintosh, where each criss-crossing seam was edged with her signature Iranian block-prints (she was born to two Iranian parents, and references her heritage often in her work), complex panelled sportswear, tailoring made up of various shards of wildly contrasting fabrics. The clothing is recognisable – a trouser, a jacket, sweatpants – and yet the end result is anything but. Working in a similar manner is breakout designer Rahemur Rahman, a designer of British-Bangladeshi heritage, who weaves naturally dyed fabrics from Bangladesh into elegant, contemporary clothing for now. “I just want to make clothes for people who dress like me,” he told Another Man last season.

Of all of these designers – regardless of divergent backgrounds, ideas, and renown – a quiet but pervasive sense of beauty unites. Each believes in the power of clothing to speak for itself. Craft is paramount: the runway spectacle, not so much.

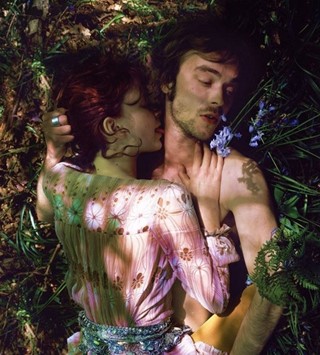

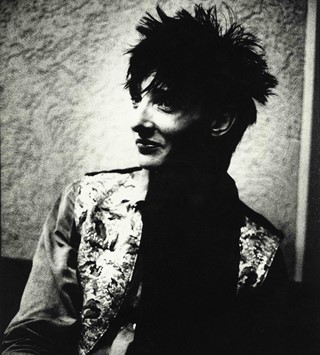

As if to distill this changing mood, Charles Jeffrey – once London fashion’s hedonistic ringleader – held his show in the hushed surroundings of the British Library, and was quick to turn the conversation back to the clothes themselves: “I wanted to invest in textiles and technique, push that, get my team to learn more about different factories, and what we can do that we’ve not done before,” he told Tim Blanks at Business of Fashion prior to the show. (Ventures, the Kolkata-based textile producer, provided the fabrics for his show; suggestively, they also supply Dries Van Noten, Comme des Garçons and JW Anderson.)

It feels like a response to fashion itself: a kind of deep breath inwards as around them the industry moves at hurtling speed. Theirs is an antidote to the kind of ‘zeitgeist’ dressing which has ruled the decade – logo-heavy, instantly recognisable luxury goods, worn briefly and discarded months later (though not before spawning hundreds of fast-fashion rip-offs). They are joining a growing chorus: how sustainable is this? How long can this ferocious production cycle last?

I still have a Craig Green shirt from the designer’s S/S15 collection. At a glance, it is simply a black cotton shirt: turn to the side, though, you see that along the seams are several fabric ties, each tied in a bow. It is quietly beautiful, and, five years on, I still wear it today. The point is: runway theatrics may fade from the memory, but good clothes last.

On the Thursday before London Fashion Week Men’s began, a collection of designers put this to the test. The collective 419, run by Olubiyi Thomas, Foday Dumbuya, who runs the label Labrum, and Daniel Olatunji of label Monad. Showing off-schedule at a space in Bermondsey, south London, they are proponents of ‘slow fashion’. Most emphatic on this is Olatunji of Monad, whose wistful clothes are drawn from workwear and yet have the feel of antique costumes: they could well have already lived a life of their own, discovered from centuries past. Such is the slowness of his brand that if you buy a piece from him, it will likely be the only piece in existence. You would be hard-pressed to find a more precious piece of clothing in London today.

“I just want to make really well-built clothes by hand that last; rather than [people having to] to buy an entirely new look twice a year,” Olatunji told me prior to the show. “Really, how many times a year do you actually have to buy a new shirt or a jacket?”