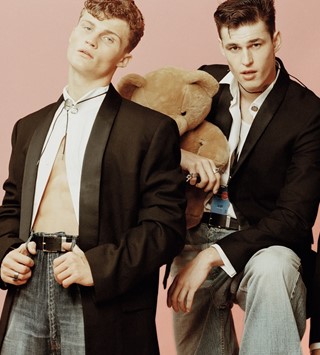

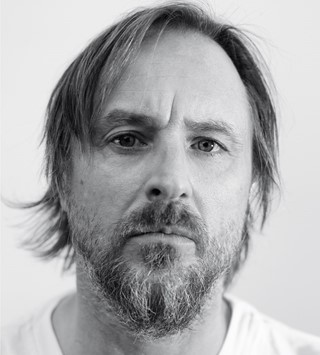

Menswear designers Olubiyi Thomas, Daniel Olatunji and Foday Dumbuya have created a unique support system, which they liken to an incubator

- TextBen Perdue

London menswear designers Olubiyi Thomas, Daniel Olatunji and Foday Dumbuya are on a mission to prove that when bureaucracy bites, and the funding runs dry, you can still make it in the fashion game. They each helm independent labels – Thomas’ is self-titled, Olatunji’s is called Monad and Dumbuya’s is named Labrum. But as 419 Collective they’ve achieved more together than they ever could apart, starting with a locked-off joint show for Autumn/Winter 2019 – off-schedule, and entirely self-produced – that was over capacity even though they barely got their invites out. All in the punk spirit of DIY.

Through friends of friends and word of mouth you can do almost anything, and 419 first put that to the test in Paris. All three had met independently, running sales appointments for their own labels out of Airbnbs, before pooling resources to hire a space together. The result was a legit showroom in the Marais that put them on the industry’s map. Now, they plan to pull off the seemingly impossible again, with a follow-up fashion show for Spring/Summer.

“We’re trying to figure out the next scheme,” says 419. “Last time you wouldn’t believe how much we spent, as in, how little! It looked like a massive production, but it’s all an illusion – we were still building the set ourselves only three hours before the doors opened. We set ourselves that target, and now we just want to surpass it. The three of us working together is always exciting.”

Here, they explain the fraudulent roots of their name, and why challenging tired African stereotypes is so important in their work.

“419 is an incubator. A way for us to come together, support each other, and do things. We couldn’t produce fashion shows by ourselves, because we don’t have the resources, but together we can. 419 originally comes from the Nigerian criminal code for fraud, stuff like Nigerian email scams, but basically it means finding ways to work the system to your benefit, turning a negative into a positive.

“All three of us were struggling individually with no support from anywhere. We didn’t have a platform like this when we started. Now we’re trying to evolve it for others to come on board. We want to seek out other designers and artists who haven’t had the limelight. And we don’t want to exclude people because they don’t fit a certain aesthetic – all our brands are slightly different, but that’s the whole idea.

“It has a bit of a punk DIY spirit, driven by having to get creative to overcome limitations. When you don’t have the right resources, you have to do things on your own terms. And it makes you more inventive when you’re limited, because you have to make things work. So, this is a support system for people to come together and find help from sources other than the obvious established ones, rather than anything to do with having a certain look. There’s enough room for everyone.

“We all have different strengths that we bring to the team, so we spread the tasks among each other. There’s power in numbers. With each project it changes, it’s not set. And we’re in this together, so none of us can just shoot off! Whoever knows the right person, or has the right skills, gets that job. It also means that when other people come in, we’re not dictating to them, but we will remain the figureheads of 419 just to coordinate and organise things.

“One thing we want to address is the African diaspora. When people think of African fashion design it’s always the same Dutch wax prints – which aren’t even African – and the bright colours. Our last exhibition was about real African textiles, and the walls were covered in fabrics from different regions. We had indigo dyes, used in Nigeria for centuries, but people immediately thought they must be Japanese. It’s an annoying assumption because craft history is treated differently in Africa. In countries like Japan this kind of thing is a national treasure!

“And when it comes to the style and shape of what we do, it’s not just about those long traditional kaftans, it’s heavily tailored and smart. Those silhouettes might influence the work, but always naturally, or subconsciously. It’s never blatant. And we want to highlight that, not follow obvious stereotypes. We don’t want to be boxed. Whatever you expect, that’s not what you’re going to find. We’ve already done it once, pulling off a show that everyone told us would be impossible, so the future possibilities are endless.”

A version of this article appeared in the S/S19 issue of Another Man.