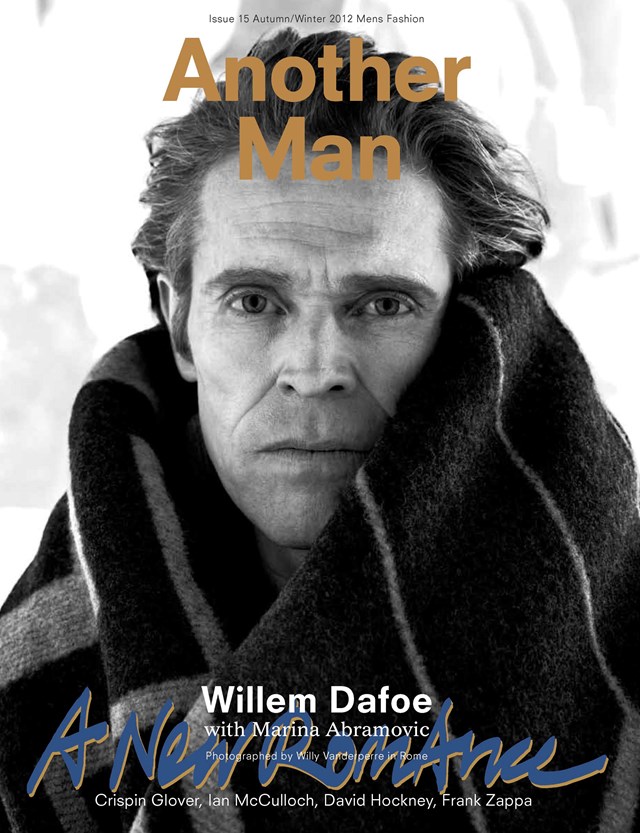

Willem Dafoe

This is the conversation of Willem Dafoe and Marina Abramovic: friends, mutual admirers, and now collaborators performing together in Robert Wilson’s play The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic. Over a late lunch of chicken fra diavolo (off menu, Dafoe) and black tea (three bags, Abramovic) at Morandi in New York, the two discuss their work, their scattershot lives, and their dedication to art. But, before we start, Dafoe has something that he wants to get off his chest...

WILLEM DAFOE: You know, I just saw a woman, I mean, you tell me because I haven’t been in New York lately, I don’t know whether there’s something in the air or a political thing but I’m walking down the street… Do you need some more water for your tea?

MARINA ABRAMOVIC: No, no, this was the whole idea, to have it very black.

WD: I think I need an espresso.

MA: Espresso or three bags, same effect.

WD: Anyway, just real quick… So I’m walking down 13th Street, a couple of hours ago, I’m looking and I think, ‘My God, that’s… Wow!’ It looks like that woman in shorts, that young blonde woman in shorts, doesn’t have a top on. She’s bare-breasted, walking down the street.

MA: What was this? Excuse me – explain to me.

WD: She was bare-breasted and she was walking down the street. And, of course, the first thing you do is you look in her eyes! (Laughs)

MA: Sure! (Joking)

WD: After you check her out, you look into her eyes to see if she seems crazy. The truth is she seemed totally sane and totally comfortable. You know, it wasn’t a sexual thing – it was just she had no top on.

MA: But how is this possible? When Janet Jackson on the TV showing her nipple was such a scandal?

WD: Well, that’s something else.

MA: What is the difference, excuse me? This is both breasts.

WD: Because that doesn’t deal with public assembly, it isn’t about being in one place, it’s about television…

A bare-breasted woman wandering the streets is little more than a local curiosity – as it turns out, she is publicising, whether for art or politics, the fact that in New York City it is fully legal for a woman to go topless. Dafoe and Abramovic’s interest in her, however, is intriguing: it must be said that, in many of her works, Abramovic has used her own nudity to make a point; and, if this topless stranger is some kind of wandering Romantic, untethered from the status quo and seeking to receive, bestow and perform her version of enlightenment, well – maybe they’re not so different.

Dafoe isn’t exactly tall, and he isn’t exactly imposing. He’s rangy, quick-moving and quick-talking, and, at 57, yoga-taut and toned. (He practices regularly, but prefers not to talk about it: “Don’t smear me with that brush,” he quips.) Dafoe has spent his career disappearing into his characters, rather than floating, celebrity-like, on the surface of them, but he has an arresting intensity, the magnetic aura of a Somebody. And just to prove the point, a man at an outside table recognises him and bounds over to shake his hand. Satisfied, the fan sits himself back down only to jump up again for one more handshake. Dafoe calmly obliges.

He is a performer whose work has spanned Hollywood blockbusters and arthouse fare alike. He’s won the approval of Europe’s great directors (Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, Lars Von Trier) and America’s (Oliver Stone, Spike Lee, Wes Anderson), and he is the rare actor versatile enough to list both American Psycho and Finding Nemo on his resume. He’s also a perennial favourite of the fashion industry. Miuccia Prada first cast him in her menswear ad campaign in 1996; he makes a repeat appearance this season, alongside Gary Oldman, Garrett Hedlund, and Jamie Bell, with whom he walked the A/W12 Prada runway in Milan. With his role in The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic – “The audience literally adores this guy,” Abramovic reports – he’s having the latest of many banner years.

Abramovic is arguably the world’s only household-name performance artist, fresh off a mammoth retrospective, The Artist is Present, at MoMA. Queues began before dawn and curled around the block for the opportunity to sit silently opposite Abramovic, who installed herself at the museum for the entire two-and-a-half-month run as the titular present artist. The exhibition was also documented for HBO. She too has won the heart of the fashion world, most notably that of her friend Riccardo Tisci, in whose Givenchy designs she is often seen and with whom she has just bought an apartment in New York. With her long black hair, cat-eye glasses (Givenchy, complete with panthers prowling the temples), and hourglass figure, she comes off as a kind of sorceress-seductress – even at 65. (As a game, she and Dafoe call each other 55 and 46: the years of their respective births.) Yet despite all that, she remains something of an ascetic. “I’m the only artist who never drinks,” she says, “and I’m very big on yoghurts.” She makes her own.

MA: How did we first meet?

WD: I’ve known of you for years through videos and books, and by reputation. Then my wife knew a good friend of yours and met you many years ago, so from there really. Also my son worked at Sean Kelly Gallery for a period, and he would beguile me with stories about you. On top of that, you lived in the co-op of The Wooster Group, the theatre company that I was with for almost 30 years.

MA: And you lived close on the street too.

WD: You were a big supporter of The Wooster Group.

MA: The first time I ever saw The Wooster Group was in 1978. That was the beginning really of modern theatre. They were one of these mysteries when the right combination of right people get together.

WD: The interesting thing with The Wooster Group is the people in the room making the pieces didn’t come from theatre. They came from architecture, they came from music, they came from dance – they came from heroin… (Chuckles)

MA: A mix of genres.

WD: Yeah, some place else. They weren’t from that tradition, so we didn’t abide by the rules of theatre and we weren’t of that culture, so I never quite identified with that. It’s just about being a community of people that serves the dialogue and the zeitgeist of that community.

Robert Wilson asked Dafoe to join the production of The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic, which he was adapting from the artist’s own journals and papers. The full production, commissioned by the Manchester International Festival and Madrid’s Teatro Real, would star Dafoe, the musician Antony Hegarty, and Abramovic playing both herself and her mother – and enacting her own death. Dafoe plays many parts in the play and speaks much of the text for the performance’s two and a half hours. “He is my father, my lover, my husband, the narrator, a crazy general who comes from somewhere, everything altogether,” Abramovic says. Dafoe describes his role as less a character, more a “function”. Wilson’s overtly theatrical, ultra-stylised stagings proved a good fit for his talents, which he doesn’t necessarily characterise as “acting”.

WD: I’m the perfect actor for Bob Wilson, because I think of myself as a dancer more than an actor and as a doer more than an interpreter. I even think of myself as an artist – not a performance artist maybe, but an artist who does performance. I don’t think of myself as an actor because the places that I am most interested in, the place that I am most engaged, don’t have anything to do with what we know traditionally as acting. So I’m very good with Bob. There were parts where he would get up on the stage, he would perform, and I’d shadow him and copy him. Once he felt like I was in the groove, he’d walk away and I’d continue. He wants you to give over to a series of actions and something will come out of that. I think copying is a good place to start from because it gives you a structure. You are not searching for your place to be creative or to have an opinion, that’s all out; you’re only doing stuff. And I think that’s when things happen. And that’s where I think I have an affinity with you, Marina. That’s why we sometimes go back and forth in discussions about acting versus performance. I mean they’re related but it gets very complicated, because there’s a class war between performance art and theatre. But then performance art is dying and so is theatre (Laughs) – TV is winning!

MA: And the internet is winning! You know, Willem, in the beginning, when Bob and I were just talking about the production, he was thinking that I would never play it on the stage. He was really afraid about how it was going to work. But then, my whole idea was to submit completely to what he wants. It’s an incredibly rewarding experience not having to be in control, when somebody else has the control. I’m so much in control of my work that I didn’t want to be in control with this. The way he puts things together, it could probably be kitschy melodrama, but the way he takes the very tragic moments of my life and twists them around, it was so much fun, but this fun is actually in a way even more sad.

WD: Well, he never gilds the lily, he never pushes the feeling that is there – he always goes against it. If there’s a very tragic story, he can’t help himself: he wants to find the humour – the lightness in it. Because if it’s just heavy, it closes you out, it’s dead, it’s done. But, if you ask me, the dark part is always there.

MA: Yes, it’s a very black humour. You laugh so much, but still heaviness is there.

WD: Which is a place that, it seems to me, you and Bob come together. You tell fantastic dirty jokes.

MA: Absolutely, really bad stuff. I love black humour because I come from the Balkans. There’s so much tragedy there and one of the ways to survive is with this kind of humour. I’ll tell you just one example: What happens when a German man, a Polish man, and a Turkish man go into a brothel in Berlin? The German goes to fuck, the Polish to clean the brothel, and the Turkish to pick up his wife. It’s very tough, you know, but it’s true – that’s why it’s so funny. I have millions of jokes about the Bosnian War.

The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic had its premiere in Manchester in July last year, then travelled to Madrid, and Basel, taking its nomadic performers with it. Even apart from this piece, Dafoe and Abramovic travel constantly. When we meet, Marina has just arrived in New York from Brazil, and will leave again the next morning, first for upstate New York, then for Kentucky. Dafoe has been shooting in Pittsburgh, made his way to New York, will celebrate Memorial Day upstate, and at some point, return to Rome, where he lives with his wife, filmmaker Giada Colagrande.

WD: You and me… we’re hardworking people and travelling fools.

MA: You know, for the last six months I feel like I’m leaving part of reality. It’s like two realities: sometimes they fit together and sometimes they are just growing apart. There are so many times I wake up and I don’t know where I am, or where my luggage comes from. I just get a new suitcase to the plane, because I have no time to deal with the reality of anything. And you too?

WD: Yeah, I know I’m travelling a lot when I wake up in the middle of the night and I don’t know where I am. Going to bed is not bad, waking up isn’t so bad but –

MA: But in the middle of the night –

WD: If you wake up in the middle of the night, you’re like ‘Where the fuck am I? ’ I have some of my most profound reflections on my life as I’m taking a piss in the middle of the night because I’m so totally displaced. Yeah, so sometimes I bump my head, sometimes I fall, sometimes…

MA: This is kind of strange, this disconnect to reality. Bob Wilson is extreme because he has been living like this for many, many years, so he truly lives in hotels, literally, from production to production. I mean we finish, we come home, but he went to Domingo, Russia, Poland, wherever the work goes. So the work is where his home is. That’s very interesting; it’s a kind of modern nomadism. But then Bob Wilson actually creates this home by taking his African masks, a vase from somewhere in Japan, a little drawing from somewhere else, and his dressing room is decorated with the things that he carries with him so it is like he is always in the same place. That’s his trick.

WD: I still like getting on planes. I know it sounds crazy, but it means that I’m going somewhere and I like that. It appeals to my sense of adventure. But the one thing I have a problem with is packing: it’s humiliating because you’re anticipating what you need. I would really love – it may be revealing something that is hippie-ish – but I really wish I could go with nothing. But I can’t because I anticipate it’s going to be easier if I take a little bit of my life with me. And the truth is, once I get there, I use nothing from the packed suitcase and if I need anything I get it there. I’m not a very materialistic person, when I know I am going to work hard, I like not to be distracted by any kind of unnecessary things. When I get involved in making things, all the petty things drop away. I think best, I feel best, emotionally – I can see. I was reading John Berger the other day, some beautiful essays, and he said something to the effect of – I hate to paraphrase – but he was talking about how art is formalising those things that in nature we can only see in glimpses. You know, it’s like prolonging those recognitions, to put your finger on something that you don’t know why, but it’s the pulse of life – that’s what engagement means to me. Sometimes it can seem superficial but in the end, I think that the quality and the energy of making things really elevates you.

MA: It’s the only ambition everybody should have because it’s so easy to put the human spirit down, it’s so difficult to elevate. It’s so easy to do that and most artists do it: reflecting the everyday shit that we have around. But the thing is, give me a solution, do something else that you can really feel better. Here’s a question for you, how do you select the work you want to do?

WD: It’s always different, it’s always changing – it’s like food. Sometimes you want different things and your body tells you what you want. That’s the way I feel. But it’s mostly about people and a sense of adventure. I’d say those two things are what guide me, particularly working in a theatre company, because how projects come about is very slow. But in movies, for example, when you’re really dealing with strangers and something gets presented to you and you have to anticipate to some degree what the experience is going to be and what interests you about it… I can never tell you literally, it’s just an instinct. Movies can go wrong in so many ways; if you try to control it, you’re fucked – you’re an idiot and you’ll be heartbroken, you’ll kill yourself or you’ll become a junkie. So, you accept that lack of control, but the one thing that you can control is why you did it. Know why you did it. And one thing that I always come back to is, ‘Do I want to be in a room with these people? Do they turn me on?’ In the same way that when I go to an art gallery or when I go to a performance piece and it turns me on, I’m ready for anything. I’m ready for failure, I’m ready for heartbreak – I’m ready for anything because I’ve got that. And to be in a room with people that turn you on and excite you, that’s what it’s about. It’s the basis of all my friendships too.