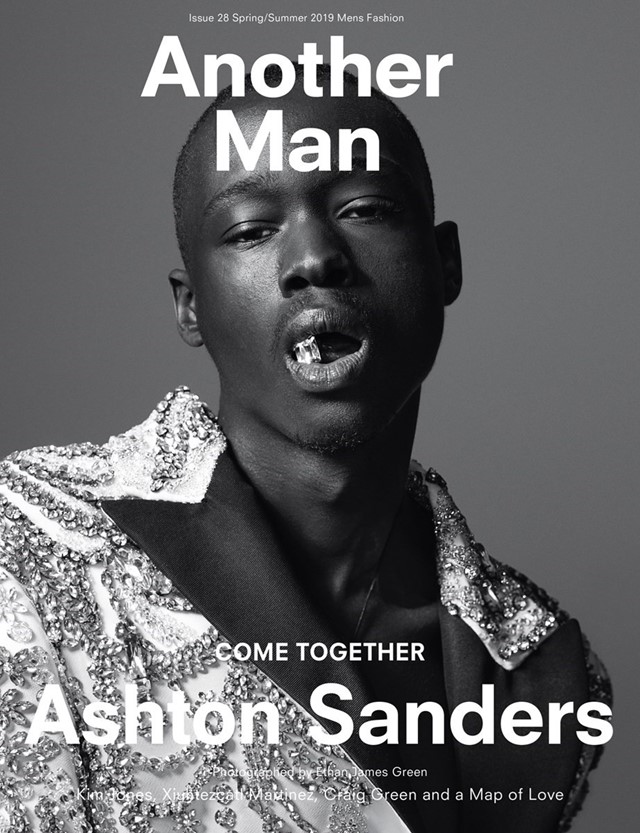

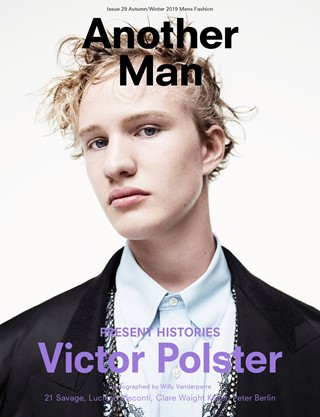

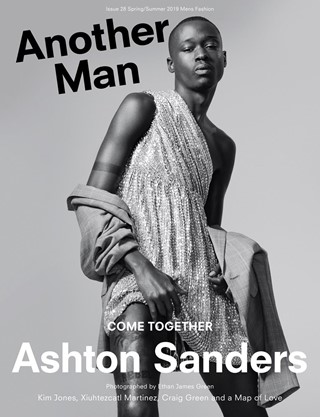

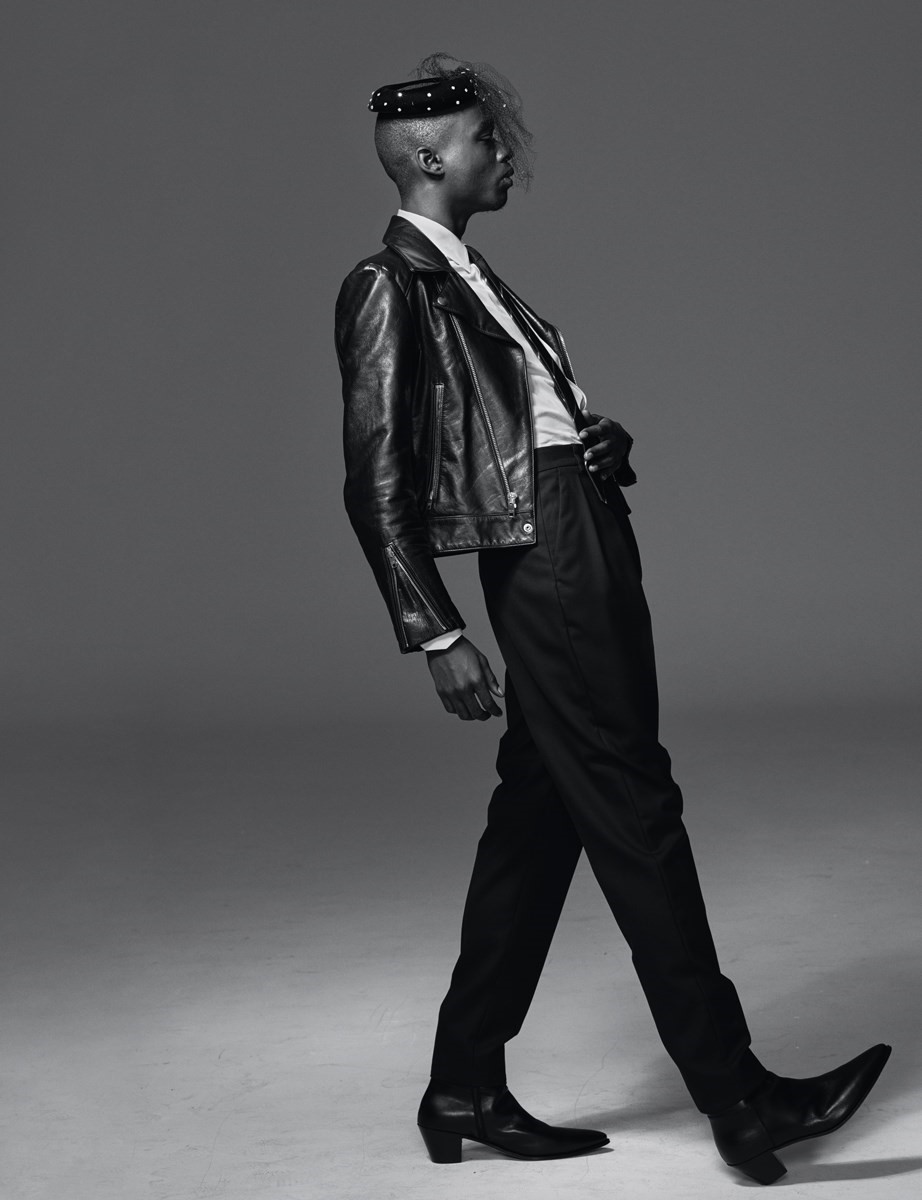

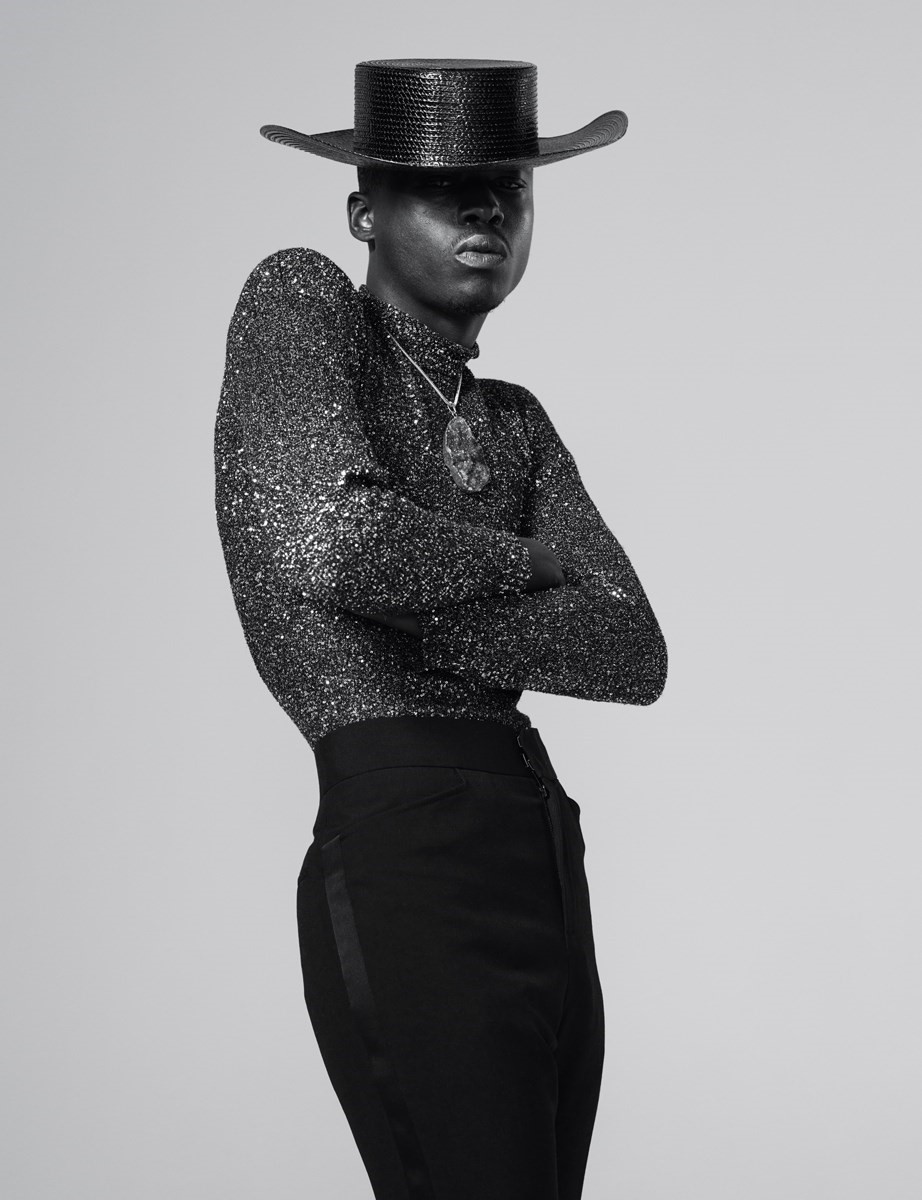

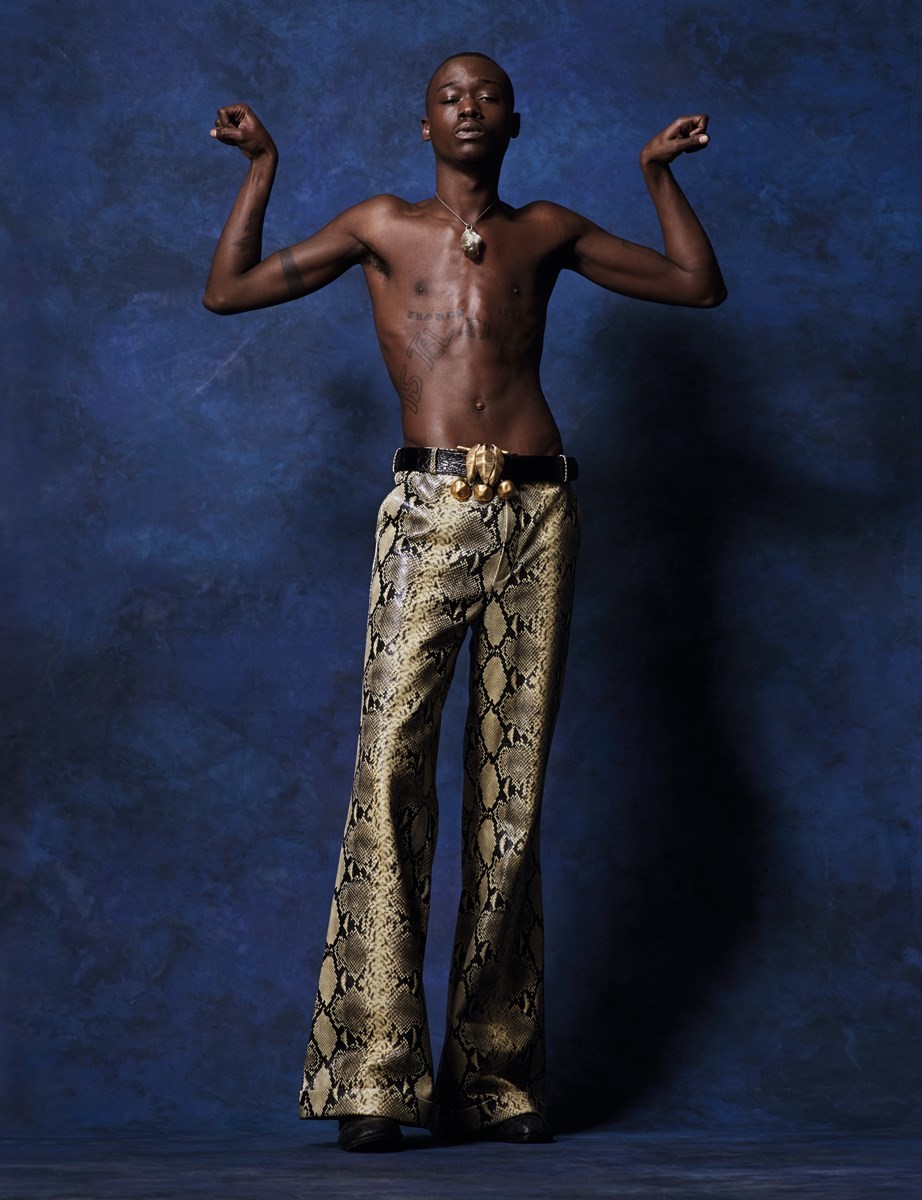

Ashton Sanders

ASHTON SANDERS’ TENDER PORTRAIT OF A WITHDRAWN GAY TEEN IN MOONLIGHT WAS A WATERSHED MOMENT IN CINEMA. FOR THE 23-YEAR-OLD ACTOR, IT ALSO IGNITED A PERSONAL COMMITMENT TO STORIES WITH A SERIOUS SOCIAL GUT-PUNCH. HERE, HE CHARTS HIS EVOLUTION FROM L.A. CHILD MISFIT TO LEADING MAN ON A MISSION.

“I was a little weirdo as a kid. My imagination was all over the place, I was definitely in my own world. I was born in Inglewood, California, but raised in Carson, California – which is basically south Los Angeles – in a predominantly black neighbourhood. I didn’t really have a lot of friends growing up. I just did my own thing. Even now, I’m most comfortable being by myself. Maybe that allowed my imagination to grow? I grew up an ‘other’, kind of a black sheep in my community. I don’t know if it was because I knew that I was an artist, and art in the black community at that time was not considered the ideal thing for a young black boy to be doing. I would be doing plays, not playing sports. Barriers are being broken now, but that was not really welcomed in black communities back then.

My father was very supportive of whatever I wanted to do creatively though. He was a fashion designer, he would go around sketching all the time, he was definitely an artist, full circle. That support was a big force getting me to where I’m at right now. That confidence starts in the home. I always wanted to be a performer, whether it was film or Broadway, or off-Broadway theatre in New York... I guess I’ve always been an introverted extrovert. So when I was 12 or 13, I started in this acting programme called Amazing Grace Conservatory, in Central Los Angeles. It was an all-black school that trained us in acting, singing and dance, and I found my artistic integrity there. I found myself there. I was able to be around all these like-minded kids, able to open up and find a community, finally. Finally, I didn’t feel judged. I was accepted for my odd quirks. They weren’t weird, or even if they were, it was, ‘that’s OK, dude’. That’s fine, that’s you. To be accepted for that? That was fucking cool.

I was also going to an arts high school at the time, so it was double training. But it didn’t feel like it, because I loved it so much. We learnt stuff people were doing in college in terms of discipline, professionalism – shit that carries over to me being on set right now, it all started there. There were ten-year-olds who were mad serious in their art. It was ‘no talking backstage’, it was dedication. You felt it in the entire, collective crew. That sparked something in me: a fire. I felt, this is what I need. This is what I want to be doing for the rest of my life. This is what fulfils me.

When I read the script for Moonlight, I had this emotional reaction that rarely happens. I needed to play Chiron. I hadn’t even booked the part and I was highlighting my lines. I knew, I knew. There was nobody else. I needed to do this, because I wanted it to be done the right fucking way, no playing around, so let’s make it happen. I had this hunger. That feeling I was talking about of being an ‘other’ growing up, I drew on that for Chiron. I was the first person the director Barry Jenkins saw. I’d just finished my sophomore year at the theatre programme at DePaul university in Chicago. I was back in LA and met Barry – I was super nervous, but we had a vibe. I got the call a week before I was about to go back to school.

There were some heavy scenes. The scenes with Naomie Harris, who played my mom, struggling with crack addiction, were really triggering. She is one of the strongest actors I’ve had the pleasure to work with, hands down. We were just locked in. It was very heavy work, very heavy shit. At the same time, shooting in Liberty City, or ‘Pork and Beans’ it’s called, we brought a different life, an actual light, to a really dangerous neighbourhood – a couple people got shot and killed during the days we were filming. But for night scenes we had these big film lights on, so children felt comfortable coming outside to play. People were outside enjoying themselves, feeling a sense of safety while we were there. It felt like we were doing something for a community in Miami that hadn’t been done before, we were exposing their identity. So there was a lot of love. It was love, and mutual respect.

And then everything went crazy. That story needed to be told. Everything happened so fast, I had to just keep moving forward. I’m opening the Rome Film Festival, I’m having dinner with the Ambassador, doing press tours, the Independent Film Awards, the Golden Globes... and then every actor’s dream, standing on that stage at the Oscars, looking out at an audience of people I’ve been looking up to. We had created something we hoped people would receive, but for that to be the final moment was the cherry on top, standing up there with this tight-knit family. I’ll hopefully work with them all again, but if not, I’m so happy I was able to do that at 20.

It was crazy, but it came to a point where I had to adapt and accept my destiny. So these last couple of years have been exactly that, just trying to stay present in it all. I have embraced spontaneity. I don’t like being in one place for too long, so this life works out for me. I just try to stay as close to my heart with my film choices as possible. I’ll never sign on to anything I don’t feel is right. I was 15 years old when I did my first ever film The Retrieval, shooting for three months in this rural landscape in Gonzales, Texas. It was really indie, small budget, breaking rules, a lot of blood sweat and tears. All for the art! It was an important story, an untold story about slavery.

So almost without me knowing it, the trajectory of my career has been brewing. From that film on, each choice I make has something to say, that’s what I’m trying to build. It’s not just artistic fulfilment, but doing something right socially, and politically, through my work. Whether it’s a studio or indie, I go in with the same attitude. It’s harder to find the right work with studio films, but Captive State, my first action sci-fi, has underlying messages that are a slap in the face to the Trump administration, which I felt was badass. I play a rebel to the system, infiltrating this authoritarian, repressive state. It’s an allegory that is right on time.

And now I’m on my way to Sundance with Rashid Johnson’s Native Son. I felt the same emotional reaction when I read that script as I did with Moonlight. Rashid is a brilliant contemporary artist, and because he comes from the art world, his mind just works differently. I felt it was a win, the dopest opportunity to be able to work with Rashid, with genius cinematographer Matthew Libatique, who shot one of my favourite films, Requiem for a Dream, and to collaborate with playwright Suzan-Lori Parks who wrote the script. Collectively, it is this big gumbo of art. It’s based on Richard Wright’s book, updated to the present, and it’s crazy how relevant it is today. Although it’s totally different living in 2019 from living in the 1930s, racially it may not be too different. It’s about the pressures that a black man has living in this world, but also the pressure of being an ‘other’. Bigger, my character, is this Afro-punk, so he already feels isolated from the world by being a black man, but there’s another isolation from being not the ‘average’ black man in America, so you get the backlash from your own people.

I did a lot of heavy work on it. So I’d be a fool to carry that home with me. It can definitely mess with you mentally if you stay in that zone for too long. It’s cool to have the freedom on set to fully lose yourself in a character like Bigger, or a character like Chiron, or Jah in All Day and a Night, another deep character study I have coming out, a story of nature versus nurture. They all demand the attention I give them, but it’s important for me to separate myself, because you can get stuck in that. And I don’t know where I’d be if I did. I find it really uncomfortable watching myself onscreen, I’m my biggest critic. It’s a blessing and curse. I’ll nitpick everything. Your foot moved, your eye twitched, why are you smiling like that?! I never watch playback when I’m shooting, it’ll mess me up. I do the art, I leave it there, and it’s up for you all to interpret it – I’m moving on to my next thing.

I love putting myself aside and putting on different personalities. It’s an escape, and it always has been. That’s the reason I started doing this. We all go through our own shit as kids, and you need a release. Whether it’s playing basketball for that boy who’s going through it at home with his dad, he can take it out on the court. Whether it’s dancing. Whatever it is. Acting has always been that for me. It’s liberation.

I just booked my first series, a Wu-Tang Clan docu-series, and I’m playing RZA. So I’m moving to New York for a while, somewhere I’ve always wanted to live. RZA has trusted me to play him, and I just have to run with that – we’ll collaborate until we get it right. I’m a sponge when I work with these great artists, how can I not be? Whether it’s having an intimate conversation with Denzel about the art; or with Mahershala Ali, who I developed a close bond with. I want to direct some day, so I’ll be taking notes and watching Rashid Johnson work; let me get inside of this man’s mind and see what sparks his ideas. I want to tell stories and the bigger you get, the more films you do, your family grows, and the horizon expands. I just want to take a dip in everything and see what happens.”

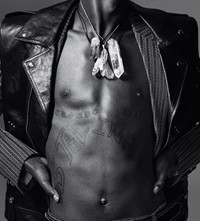

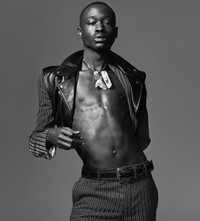

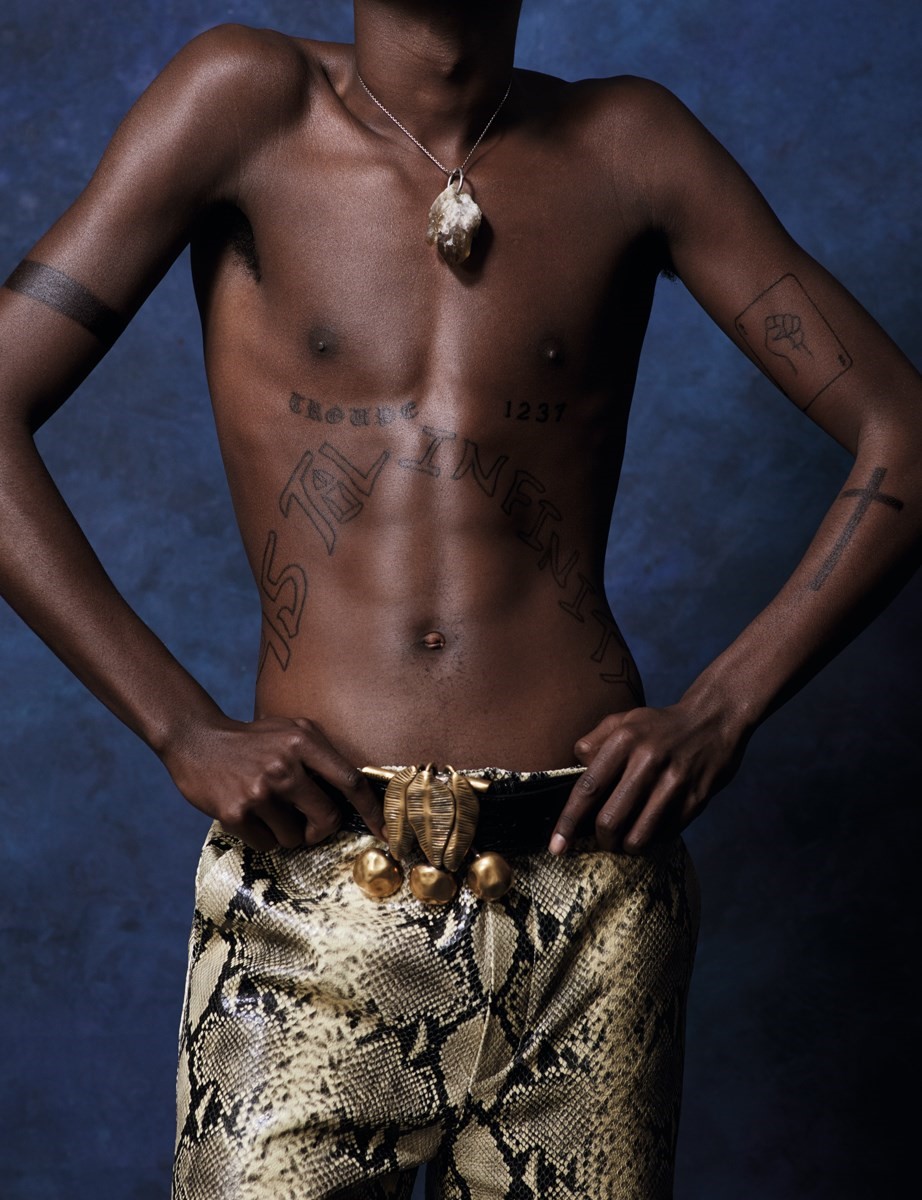

HAIR Cyndia Harvey at Streeters MAKE UP Petros Petrohilos at Streeters MANICURE Adam Slee at Streeters using Sisely SET DESIGN Julia Wagner at CLM PHOTOGRAPHIC ASSISTANTS Clément Dauvent, Andy Moores DIGITAL TECHNICIAN Nick Rapaz STYLING ASSISTANTS Vincent Pons, Sophie Gaten, Max Saward, Allegra Bartoli HAIR ASSISTANT Mike O’Gorman MAKE UP ASSISTANT Sunao Takahashi SET DESIGN ASSISTANT Marcs Marcus, Nia Samuel-Johnson PRODUCTION Sylvia Farago Ltd POST PRODUCTION Dtouch