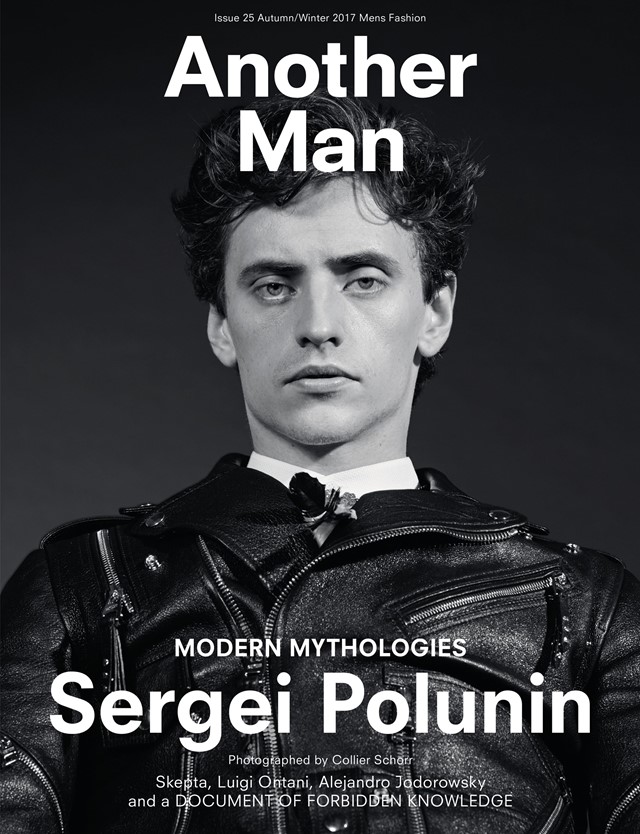

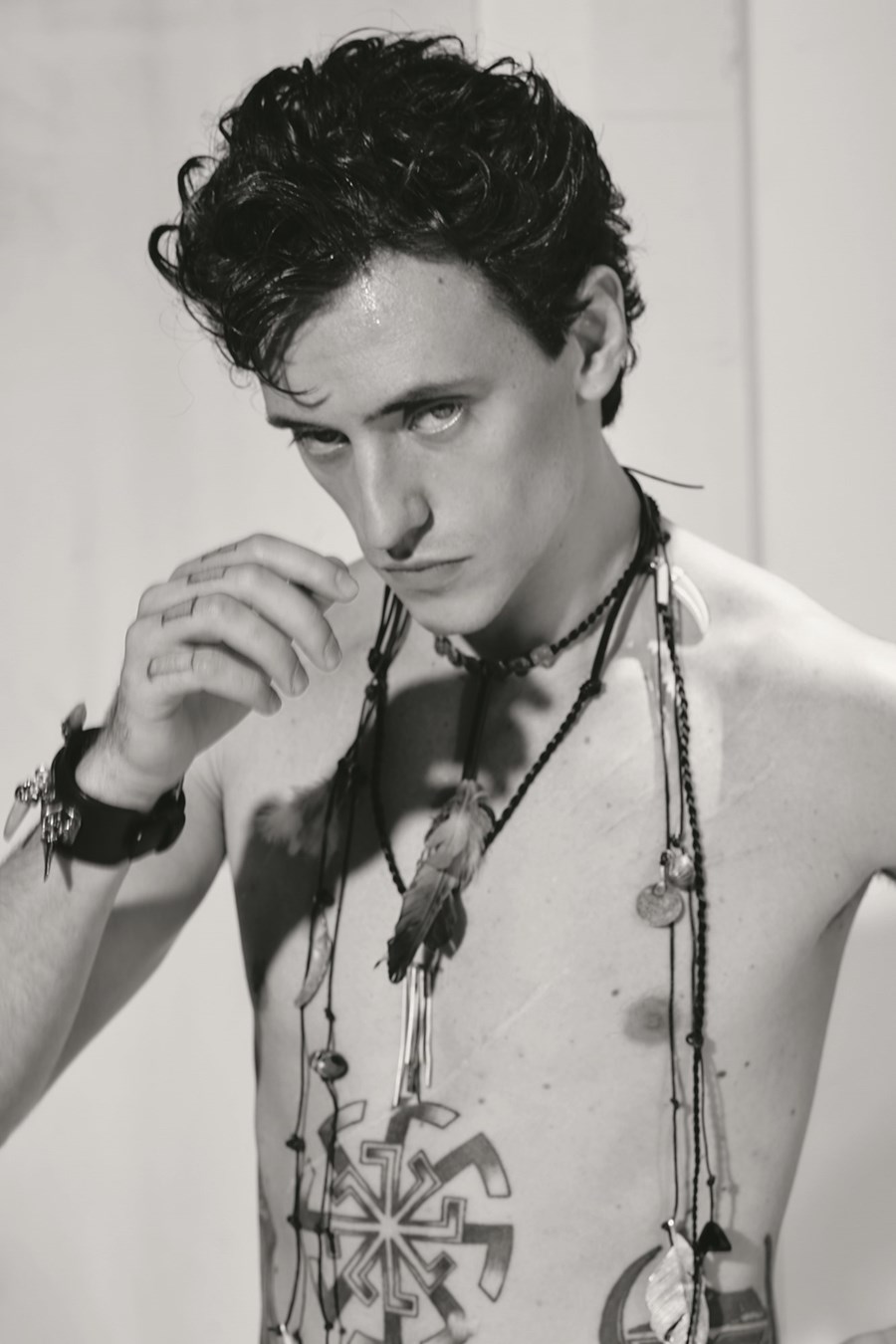

Sergei Polunin

RUSSIAN PRODIGY Sergei Polunin HAD SOARED TO THE SCORCHING HEAVENS OF BALLET. BUT, TORMENTED BY ITS SUFFOCATING STRICTURES, HE WALKED AWAY FROM THE WORLD OF DANCE AGED JUST 24. NOW, WITH DEMONS FINALLY CONQUERED AND HIS SIGHTS SET ON CINEMA, THE FIERY PERFORMER IS READY TO RISE AGAIN.

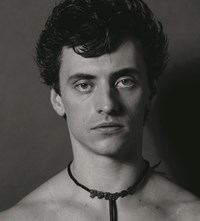

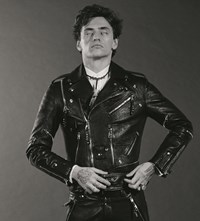

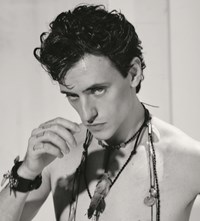

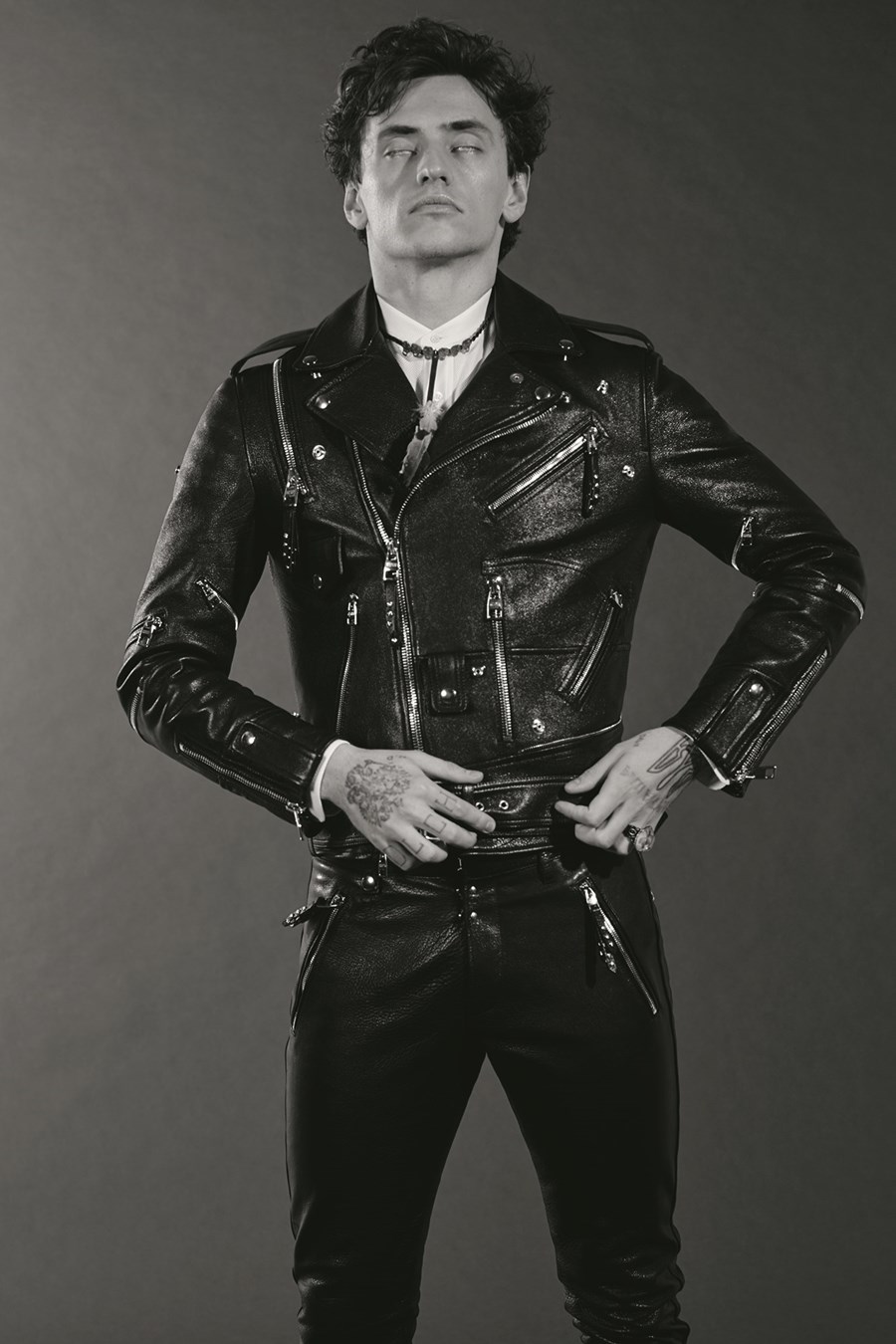

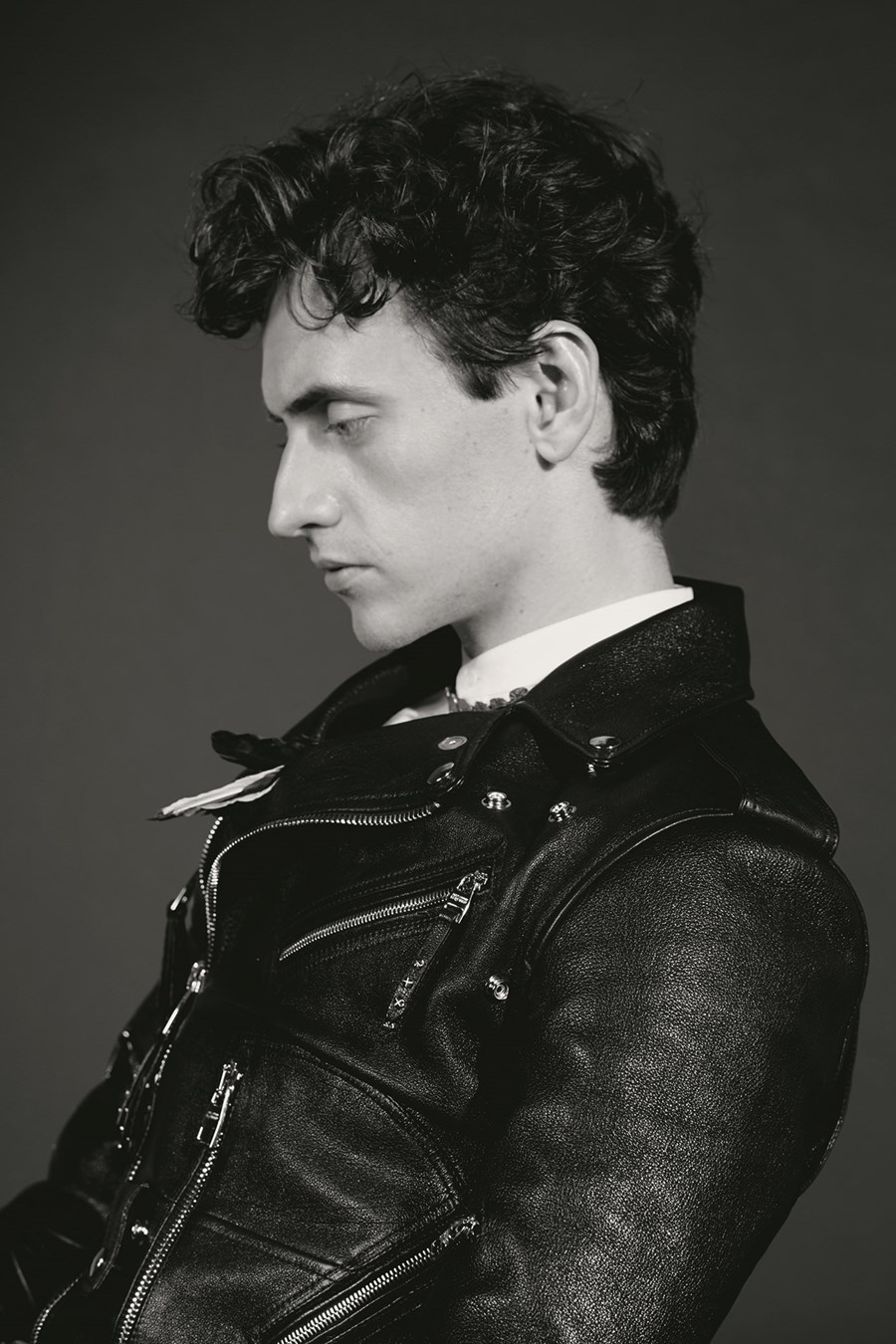

Sergei Polunin seems like a creature from another time, an era of fairytale, when the thin silk that separates myth from reality was at its most fragile. It’s as if he has stepped directly through the veil, from a place where darkness is lit by flames and hooves echo across cobblestone.

He seems completely out of place, here, in Los Angeles, in midsummer 2017. He moves like a pale ghost through the sunburnt crowds hunched over their phones along Hollywood Boulevard. Tightly muscled, tall but still delicate somehow, he exudes a romantic, Byronic kind of elegance. He’s beautiful, but in the way of silent movie leading men – Valentino, Keaton – a face of angles and extremes.

It is only when he finally sits down in a red leather booth in the city’s oldest restaurant (Musso and Frank, circa 1919) that he seems to have arrived in the kind of present that suits him. A tuxedoed waiter takes his order; the wood table glows with polish, there are fine linens, real silver. Polunin smiles, looks around and nods approvingly. Then he takes a breath and, in softly accented English, begins to tell his story.

“It started with Take Me to Church,” he says quietly, “suddenly, people’s whole approach, their whole behaviour changed. I realised that maybe… that I can possibly change something. That I shouldn’t be a weak person who quits. And I realised that something might be done that – if I quit – is not going to be done. So that’s how it all began.”

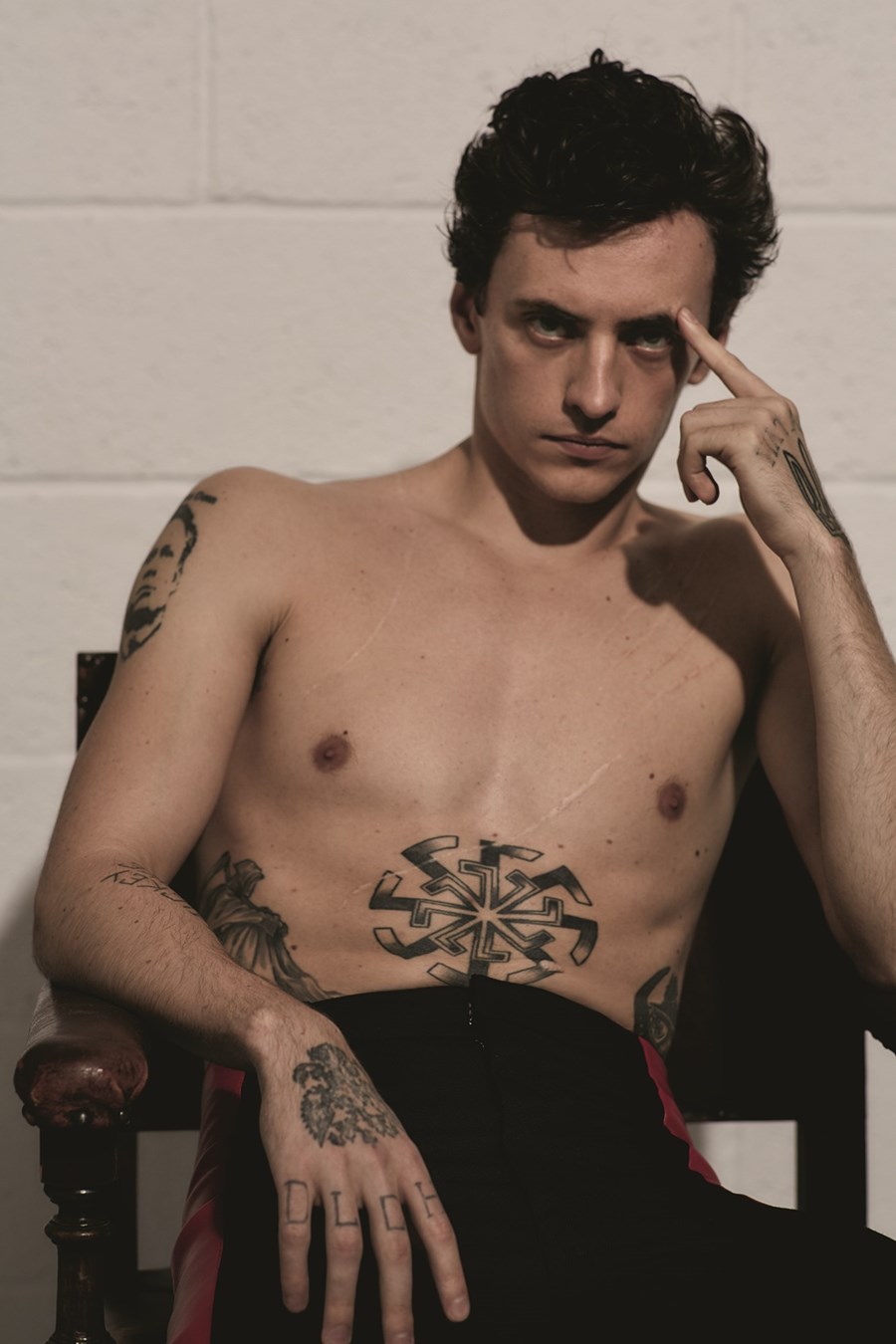

For those who don’t know who Polunin is, there’s a simple introduction. Go to YouTube, type in his name and step back in wonder. At last tally, there were 20,860,577 views of a video, directed by photographer David Chapelle and backed by Hozier: Take Me to Church captures Polunin’s last dance, his farewell (at age 24) to ballet, an art he’d studied since the age of four, an art to which (as he tells it) he had sacrificed both his childhood and his family. In the video, Polunin takes traditional ballet and turns it into catharsis. He seems to hover in the air, to float, to fly. His body is lean, nearly naked, covered in tattoos. His face shows a mix of emotion: vulnerability, frustration and, finally, elation. It’s intoxicating to watch.

“It started with Take Me to Church...suddenly, people’s whole approach, their whole behaviour changed” – Sergei Polunin

In the 2016 documentary Dancer, Polunin’s story is chronicled in all its mythic rise-and-fall glory. It goes something like this: born in relative poverty in the Ukraine, he was crowned a ballet prodigy soon after he took his first steps. His mother, father and grandmother did everything in their power to put him in the best schools, offer him the best possibilities. This meant separation, his parents’ eventual divorce, Polunin on his own in London as a pre-teen onward. He was the top student at the prestigious Royal Ballet Academy and aged 19 selected as the youngest principal dancer ever of the Royal Ballet. He was feted and celebrated. He was critiqued and acclaimed. His rebellions were tabloid fodder. His victories were breathtaking. To watch Polunin dance is to be awed. But it was all too much, a fast build to a dramatic end.

On 24th January 2012, just two years after joining the company, Polunin announced his resignation, claiming loudly that, “the artist in me was dying”. There was a sojourn to Russia, a series of demeaning TV competitions, and eventual tutelage under renowned artistic director Igor Zelensky. There was success and there was turmoil. Finally in 2014, Polunin decided to call it officially quits. He met up with Chapelle in a sundrenched Hawaiian church to film Take Me to Church and to take what was to be his final bow.

Except it wasn’t.

“Take Me to Church gave me the opportunity to experience collaboration,” Polunin explains. “I was like, ‘Oh, that’s what it is. That’s how it should feel.’ And suddenly, I wanted everybody to experience that. I wanted to create movies about dance, and create more pieces like that because I realised that it’s very, very important to crossover, to share ballet with everyone.”

Instead of ending his career, the video ignited it. Polunin found a whole new audience, the vast world watching from their computer screens. The piece went viral – and so did Polunin. “I had quit ballet, but I realised that was weak of me. That what I needed to do was share ballet,” he says.

Polunin became an overnight internet sensation. The comments poured in, people from all over the globe confessing their admiration, thanking him for the inspiration. He and Chapelle had touched something deep. And Polunin began to rethink his retirement. “I started to see that the ballet establishment had to be broken. Ballet is stuck. It’s the only art form which didn’t evolve and it lost a few things – because the best directors, best musicians, they work where the biggest output is, where you can reach bigger audiences. Ballet is very closed and it’s for elitists – it shouldn’t be like that. I think everybody should enjoy it.”

“Dance is important. It’s that language that everybody understands. It’s a powerful tool to open people’s minds” – Sergei Polunin

Since the Take Me to Church phenomenon, Sergei has formed his own foundation, the Polunin Project, with an aim to bring ballet to the masses. “It’s a spiritual-like experience,” he says of ballet, “and it’s possible I think to transfer that. I’ve been trying to bring dance closer to people, to wider audiences. That’s why we created this project, to move, in any way possible, dance forward. So we have the photographers, the music people to collaborate and to create art. And as well I want to create movies about dance. I think it’s very, very important to crossover. Ultimately, my vision is ballet has to open up to agents, to managers, to TV, to videos, to Netflix, to YouTube. Because I don’t see why people who cannot afford a ticket can’t watch it at home. You watch sport at home. Once a week to watch ballet would be, I think… transcendent.”

Despite this enthusiasm for dance, Polunin is still very much the rebel when it comes to defying the ballet establishment. His much talked about exit from the Royal Ballet still obviously hits a raw nerve. He bristles when talking about his experiences with the more conservative aspects of the art. His voice grows lower, tense. “Dancers work 11 hours a day, six times a week. When I was working as a principal dancer that was the hardest I ever, ever worked. And you will finish your career after 10 years.” Polunin points to his head, smirking, “because after 10 years you might start thinking. And realising that it is maybe the worst job to be in. The money is low. Crew get more money. Musicians get unions. And everywhere dancers get treated with the least respect. I still haven’t worked it out. The approach to dancers is like to kids. I never see stage people talk to musicians that way. But with dancers it’s okay to do that.”

Polunin checks himself and softens. “But ballet itself – it’s important. Dance is important. It’s that language that everybody understands. It’s a powerful tool to open people’s minds. It’s some subconscious thing, a connection we all have. Kids dance before walking. It’s our truest nature of being. It’s true spirit.” He pauses. “And then, slowly and slowly, as we grow older, we get more and more baggage and life changes you. We are more scared of things, more fearful. So how to eliminate that? We have to go back to how we were as a kid, because that’s our truest nature. And with ballet, that is how I’m trying to come back to this state of mind. Because that’s the purest state. Tribes dance. Every country has a national dance. In the clubs we dance, we dance at weddings. Dance is a language. It’s a language that we need, like music, to survive.”

This is how Polunin talks, at 27 years old. In part because he was raised in ballet, amid structure, discipline, beauty and philosophy. He grew up, matured, became a man, within an older art. A more refined one. And despite his issues with the constrictions, the rules, the exhaustion, and the exploitation, ballet has formed and shaped him – not just his body, but also his mind, his way of thinking and being.

The dedication he has to share dance with the world, is also a reflection of the stubborn perseverance he learned from many years and countless hours committed to his craft. It is because of this perseverance that, today, Polunin is not just surviving, he’s thriving. He’s dancing all over the globe, performing just the past evening for thousands at Los Angeles’ legendary Hollywood Bowl. And now he’s moved into acting as well – he’ll be appearing in not one, but four upcoming films, among them the spy thriller Red Sparrow with Jennifer Lawrence, the Agatha Christie classic Murder on the Orient Express and in the highly anticipated biopic of legendary ballet bad boy Rudolf Nureyev, White Crow. Directed by Ralph Fiennes, the latter film was rumoured to star Polunin as his infamous predecessor, but today Polunin quietly explains there have been some changes in casting. He will say only that, “I’ll do whatever they need me to do for the film, the very best I can do it.”

“I’m learning a completely new skill and that’s very exciting,” he says of acting, “and acting is not just acting. You learn about yourself. That’s what I think is special about it. Before I thought acting was like, ‘Oh, I learned a new skill.’ But no. It requires a much deeper understanding of existence and of being human, what it is to be human. You are really searching through your own memories – you have to really know who you are. Going into childhood memory.”

“I’m prepared to destroy everything I have to have that opportunity to feel free” – Sergei Polunin

What Polunin also seems to enjoy about acting is the collaborative nature of it, the family of artists necessary to make a film. “What I really loved is being together,” he admits. “It’s working with others. It’s not like you’re by yourself doing something. You are a team. You’re one with the camera, you’re one with the director, you’re one with your co-worker, so it’s like you are creating together. You feel like you are a part of something, rather than doing it all by yourself.” He pauses and thinks for a moment.

“I want to be able to feel freedom. I never want to be owned by anything and be stuck with anything. It’s like this…” he reaches down and picks up a heavy silver knife in one hand, clutching it tight in his fist and pointing to it. “We think if we let go of a person, let them free, they’re going to disappear. But you don’t need to clench and suffocate people. It’s on many levels – on the parenting level, on working level, on friendship level, on a social level. It’s important to push that boundary. What I’ve found is that by letting go of a person, letting them free, he’s still yours, but there is a still a feeling of freedom.”

Here Polunin stops and turns his fist over, opening his fingers up, slowly, dramatically. The knife rests gently on his open palm. Polunin smiles broadly. “It’s a feeling of freedom,” he says again, “that’s what’s important. That’s what I always fight for and I’m prepared to destroy everything I have to have that opportunity to feel free. Everybody wants to control or own. I’m against that. I felt like I was owned for so long. I was looking to feel freedom. When I quit Royal Ballet… it would be amazing if I could have stayed and found that feeling of freedom. But instead, I destroyed everything and went all the way down, to be able to climb up.”

Polunin shakes his head. He looks suddenly older, wiser: “For many years, I had a negativity in me, and I never used to be like that. It’s just that life takes a toll on you and then you start. And it’s comfortable. Being negative is very easy. Being bad is easier. It takes a lot of strength to be on a good path and that, for me, was a conscious decision. Let’s go up. Sometimes I went down and I just had to rebuild, build, build. Slowly regain. With Take Me to Church, kids were watching, were being inspired and I realised that this inspiration I was giving them, this positive message, was a stronger tool than trying to destroy things. I had to learn not to destroy because you’re hurting people around you. Even now I’m always on the verge of destroying things.”

Polunin trails off… a shadow passes his face. Then, he shakes it off, looks up and grins. And he is young again, joyful, the shadow gone.

Spend time with Polunin and you realise what defines him most is this earnestness – emotion and truthfulness always moving across the surface for all to see. He speaks his mind, for better or for worse. He is self-obsessed and self-aware. He is 27 in 2017 – beautiful, famous, volatile and complex. And there is more to come. More dance, more art, more self-exploration. “You always have in life, different paths. And you choose,” he says, “But for me it is always choosing to be an artist before anything. Because what is more important than art? Without it, we’d be nothing. We’d have nothing. The artist – he creates a building, he designs a car, a rocket. The world needs an artist’s vision. Who would we be without the artists to design our clothes? Or make music? And the thing is, I think art is in everybody. It’s important for people to be creative. To sing, to dance. You need creativity because creativity gives you confidence. And confidence is very important, because it gives you spirit. If your spirit is not broken – nothing can take you down.”

The A/W17 ‘Modern Mythologies’ issue of Another Man is out now. Purchase a copy here.

Hair Matt Mulhall at Streeters; Make-up Laura Dominique at Streeters; Set design Andrea Cellerino at Streeters; Photographic assistants PJ Spaniol, Will Grundy; Digital technician Stefano Poli; Styling assistants Reuben Esser, Rhys Davies, Steph Francis; Retouching Two Three Two; Production Sylvia Farago Ltd.