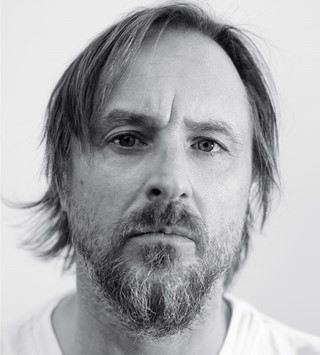

“It came down to just wanting to make clothes again,” says Parnell Mooney, as his eponymous label returns for Spring/Summer 2020

- TextJack Moss

Last summer, Rory Parnell Mooney moved into a new studio; a small, light-filled room in a warren-like building in Stratford, east London, once a hospital for sufferers of tuberculosis. He ripped up the carpet (“it was this horrible stained grey school carpet,” he says) and sanded the floors; built a pattern-cutting table, painted everything white, pinned photographs on to the walls. Then, he started making clothes again.

Parnell Mooney was born in Galway, Ireland, and began his eponymous label on graduation from Central Saint Martins in 2015 (he was part of the final year to be taught by the late Louise Wilson). He showed as part of talent incubator Fashion East for four seasons, and found international stockists – including Dover Street Market – for his collections, which married the religious garments he encountered as a child in Ireland with a sense of youthful rebellion (one season ran with the slogan ‘Nancy Boy’, in reference to the song by British rock band Placebo).

“I don’t want to be apologetic,” he says over the phone from Paris, where he will show his S/S20 collection to buyers and press this week, marking a return after a two-year break. “It was never really about, ‘oh, it all got too much for me’, or anything like that. I just thought: maybe I want to teach, maybe I want to make money, maybe I want to have a life outside of fashion. But then it came down to wanting to still make clothes. And I think now I’ve realised you can do both.”

Parnell Mooney calls his new way of working “organic” and “natural”. The first thing he made was a hat: the previous summer, he had walked across Portugal, and he based it on a wide-brimmed hiking hat he had worn. He then remade it in various fabrics – moiré silk, plaid, cotton poplin – and added a tie under the chin (various iterations are in the final collection). The same was done with an army-issue shirt he had purchased at Oxfam, nearly a decade previous. “It wasn’t like: ‘oh, I’m going to sit down and research this, and think about it for hours’,” he says. “With this collection it was about doing something physical and see what happens.”

The resulting collection, shown under the moniker Parnell Mooney (“I think I wanted to remove myself personally from it a bit, and make it into more of a brand”) finds common ground with his earlier work in its exploration of extremes: “I think if I was to have two reference points it would be the clothes that everybody uses on a daily basis,” he says. ”And then on the other hand, the most ridiculous, luxurious, overblown couture. I’m not really interested in the middle ground.”

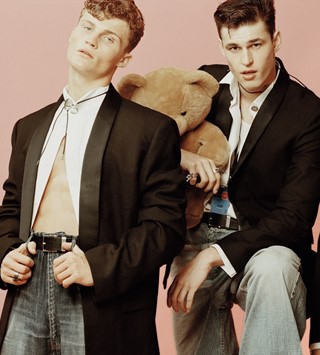

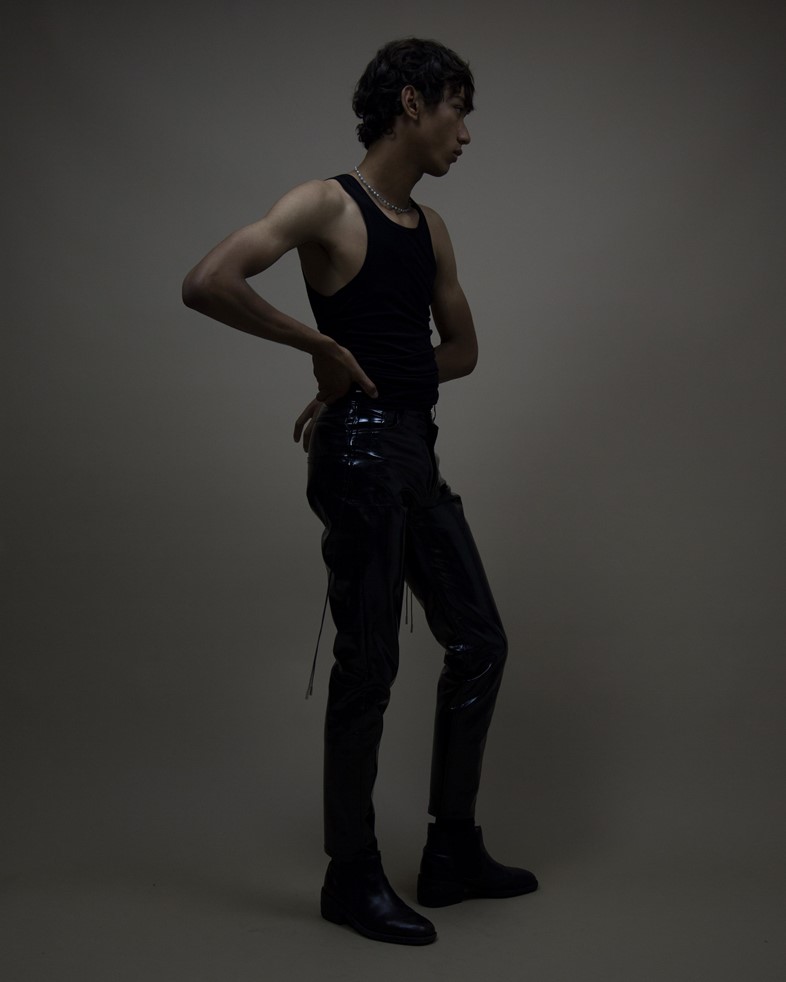

It makes for familiar pieces, somehow distorted: “I feel like everything should be counteracted with something a little weird,” he says. Skimpy cotton jersey vests and T-shirts – in various colours, from tangerine and baby blue to olive green, all new for the designer – are distorted with adjustable drawstrings along the seams; denim and patent faux leather jackets are cropped and pinched at the waist, revealing a flash of the wearer’s midriff; shirts might be slashed open across the shoulder seam.

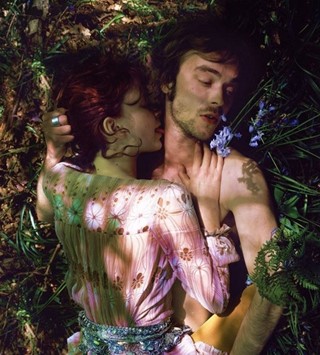

Others borrow from the sense of abundance of couture: moiré silk – in coral, lilac and powder pink – is used throughout, while cocooning overcoats – in long and short lengths and fastened with a series of bows – briefly recall the work of mid-century couturier Cristóbal Balenciaga (Parnell Mooney often cites the designer as a reference, and one of his pieces featured in the exhibition Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion at the V&A in 2017). Sailor-collar shirts, mini cotton ‘skirts’ (worn underneath trousers, like boxer shorts), and bonnet-like hats – in often clashing fabrics – suggest a kind of queasy innocence. “I want it to all feel a little bit wrong,” he says.

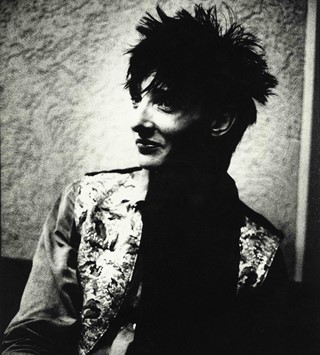

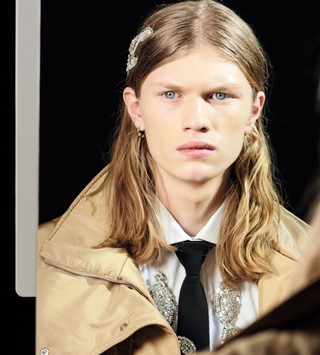

For this returning collection, he has chosen to forego a runway show in lieu of a series of portraits of emerging model Luke Solo, taken in the Stratford studio, which he says gave him more control (“I think putting the whole season down to 20 models and four minutes on a catwalk is a bit of a headfuck,” he says). Solo’s poses took inspiration from the photographs on the walls: Freddie Mercury, in various contortions as he performs on stage in the 1980s, and John Travolta, circa the opening credits of Saturday Night Fever. Others are stills from the 1980 erotic thriller, Cruising, which Parnell Mooney first watched alongside Wilson in her Central Saint Martins office.

Cruising, he says, provides something of the key to the collection: “It’s this kind of weird, ferocious performance of sexuality,” he says of Al Pacino’s protagonist, a cop who infiltrates the queer cruising scene and S&M leather bars of New York’s West Village to track down a serial killer. A sense of fetishism lurks throughout: whether the wipe-clean patent faux leather, hanky code-referencing bandanas, or muscle-bearing tank tops – the latter credited to a newfound love of the gym.

There is an unnerving, seductive feel to these pieces, but the collection rests on a simpler kind of desire: the want for uncomplicated, individual items of clothing for men. “I really wanted to hone down on separate garments – a pair of jeans, a T-shirt. I thought about how I dress: I don’t want things that are overly complex, or annoying to put on,” says Parnell Mooney. Of the collection itself, he is resolute: “I think this is what men want to wear.”