King Krule

Archy Marshall AKA King Krule IS 19 YEARS OLD, AN AFRO-PUNK-JAZZ PRODIGY LIVING WITH HIS MOTHER IN SOUTH LONDON AND, QUITE POSSIBLY, THE NEXT GREAT HOPE FOR BRITISH MUSIC.

Paul Morley IS 56 YEARS OLD, AN UNOFFICIAL AMBASSADOR FOR MANCHESTER LIVING IN NORTH LONDON AND, ALMOST DEFINITELY, BRITAIN’S GREATEST POP COMMENTATOR.

THEY COLLIDED ONE SUNDAY EVENING AT THE BETHNAL GREEN WORKING MEN’S CLUB…

“I GOT INTO GRAFFITI WHEN I WAS 13. I HAD A FRIEND WHO WOULD PAINT A LETTER THE SIZE OF US! I THOUGHT THIS WAS INCREDIBLE – YOU CAN PAINT A LETTER THE SIZE OF A BUS! I WANTED TO DO THAT. I WANTED TO MAKE MY MARK. I WANTED TO MAKE MYSELF BIG, MAN!”

There is a lot of space in London, but it can often seem crowded. There are lots of spaces in London, big and small, smart and battered, that even someone living there all their life will never see or visit or know about. Ghost spaces that exist and do not exist at the same time. There is much about London that is completely familiar, even comforting, and much that is strange and alienating. It can feel very empty but it can also feel as though it is overflowing with too much movement and too many people all heading at the same time in different directions, making marks or keeping themselves to themselves, all of them competing with each other for something never really named, a form of survival, a form of making it from one day to the next without disappearing through the cracks between one space and another, a form of having fun, and taking stick, and handing it out. The people in the city are all in it together and all in their own separate worlds, connected and disconnected by time and place, sharing the city with the living and the once-living.

“IT’S ALL ABOUT HOW YOU FIND YOUR OWN SPACE AMONGST ALL THE CLUTTER AND COMMOTION AND ALL THE PEOPLE, NOT QUITE LOOKING YOU IN THE EYE SO THAT IT’S HARDER AND HARDER TO SEE EYE TO EYE WITH ANYONE.”

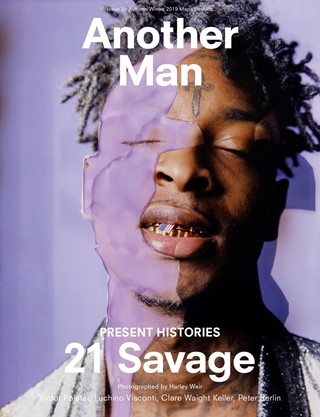

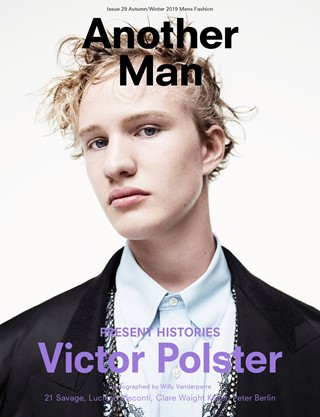

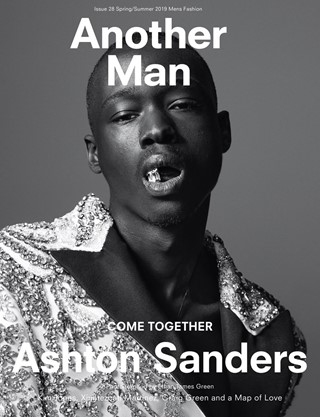

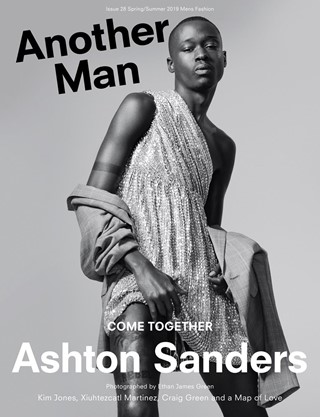

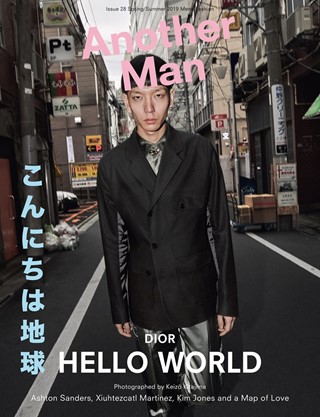

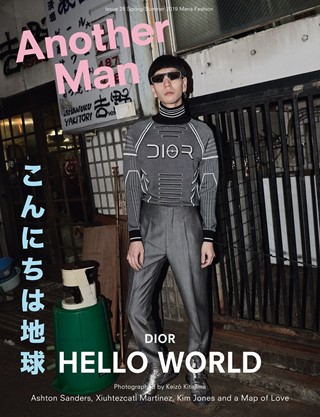

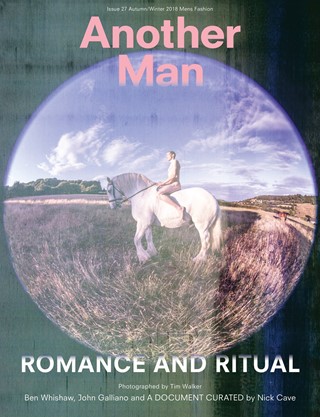

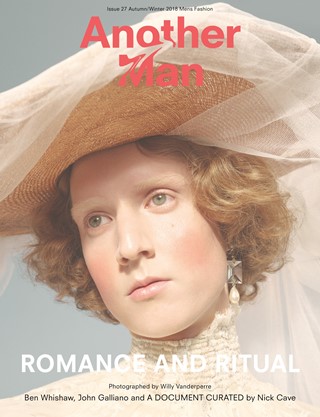

In a solid, tired but dignified brick building with a century or so of history in a crowded, built up area of London out to the east of the city, just off a busy, filthy Victorian high street constantly pummelled by traffic, weather and people, an individual born and bred in South London finds himself at the centre of attention. The individual is being photographed for the cover of Another Man because this individual is finding more and more space for himself in the city and the world around it by becoming the sort of individual people are interested in, because of how he looks, what he does with his time and the noises he makes.

“I LIKE FEELING OUT OF PLACE. I LIKE WANDERING AROUND LONDON GETTING LOST. THE LONELY GUY LOOKING FOR A FUCKED-UP HEADLINE. SOMETIMES IN PECKHAM YOU WALK INTO A ROOM AND THERE ARE LIKE TEN CRIMINALS JUST HANGING OUT. YOU JOIN IN. YOU TURN A CORNER AND THEN ANOTHER CORNER AND YOU COME ACROSS AN ABANDONED SPACE, JUST WAITING FOR SOMETHING TO HAPPEN. THERE ARE PARTS OF SOUTH LONDON THAT ARE LIKE LAGOS – NO-GO ZONES, NO POLICE, AND YOU JUST KNOW SOMETHING IS GOING TO HAPPEN, EVEN IF SOMETIMES IT’S NOTHING MUCH. THERE’S ALL THIS CHAOS AND ALL THIS QUIET, AND EVERYTHING IN BETWEEN.”

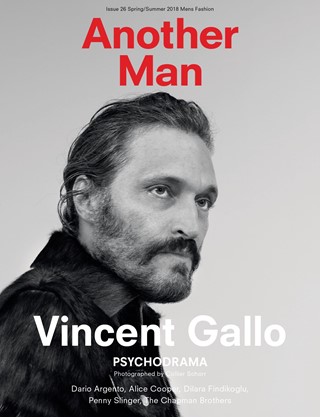

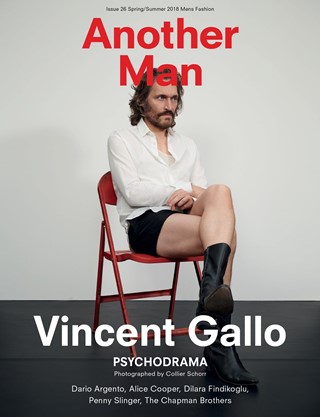

This new talent is 19 years of age and it helps in his quest for individuality that he resembles very few other individuals of his age, not least because his hair is ginger to the point of being orange and his skin is as pale and see-through as cigarette paper. There’s faun-coloured down on his chin and his frame is as threadbare as someone who is either wrecking his life through steady self-abuse or someone who is “making it”, turning his body into a glamorous, skinny symbol of charisma in a heroic intent to stand out from the crowd. He has the look of a frail, vaguely determined someone whose songs – because naturally he is a songwriter – deal with his dissipated surroundings; all that twisting and turning, local and international, churning and static, rotten and amazing London, and love lost, girl and boy stuff and everyday life, which is all he has known, and his songs pursue the dramatic tension of feverish emotion that sizzles below cool smoked vocals handing out an illusion of effortlessness. Some say his music, which sounds like a lot of other music – expertly chosen and synthesised, but all out of his own head – is the very sound of London, sourced through a kind of séance; the sound of a city that’s seen it all and ain’t seen nothing yet.

“LOTS OF ARTICLES ABOUT ME BECOME THIS LIST OF ALL THE DIFFERENT MUSIC I LIKE AND STARTED LISTENING TO FROM WHEN I WAS A KID. THIS CAT IS NEW AND INTERESTING BECAUSE OF ALL THE MUSIC HE HAS LISTENED TO. TO ME, IT’S NO BIG DEAL. IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN MUSIC, WHY WOULDN’T YOU BE LISTENING TO EVERYTHING THAT IS OUT THERE? IT’S ALL AVAILABLE. IT SEEMS STRANGER THAT YOU WOULDN’T BE GOING OUT OF YOUR WAY TO FIND IT. IT’S PRETTY PATRONISING, REALLY – THAT I AM LISTENING TO LOTS OF MUSIC AT A YOUNG AGE, THAT I SOUND HOW I DO EVEN THOUGH I AM THE COLOUR I AM. I WAS EXPOSED TO SO MUCH MUSIC, AND THAT WAS JUST NATURAL. I LISTENED TO EVERYTHING I WAS EXPOSED TO AND I WAS OPEN TO EVERYTHING, ESPECIALLY LIVING IN LONDON. I DIDN’T HAVE IDOLS OR ANYTHING. IF ANYONE WERE MY IDOLS, IT WAS MY MUM AND DAD. THEY WERE SO INTERESTED IN MUSIC, ART AND FASHION, AND I GREW UP IN THAT ENVIRONMENT – NO BORDERS, REALLY. I SEE PICTURES OF THEM WHEN THEY WERE YOUNG AND THEY JUST LOOK SO COOL.”

In this building with its own history and meaning – but today being used as a set to frame the individual inside a world that suggests toughness, togetherness, persistence, edge, London, gangs, boyhood, delinquency, shabby glamour – there is some evidence about the figures this individual is being compared with, because of his look, because he is from deep inside the mass and mess of real and mythical, carved up and crushed together, Capital and corrupted London, from deep inside the unfolding, folded-up history of pop, because he has a voice and something to say about loneliness and desperation, and insight, knowledge and experience allegedly beyond his years.

There are racks of clothes selected to dress the individual as something that quickly announces that he belongs to a very particular tradition, but is of the moment. A brief glance at the colour, shape and cut of these clothes indicates that he is considered to be a little bit 40s bebop, a little bit 50s rock and roll, a little bit 60s soul rebel, mod, and then more firm skinhead than soft hippy, a little bit 70s glam, punk, post-punk, ska, DIY, Blockheady, a little bit 80s no-wave, Braggy, baggy, Browny, a little bit 90s grunge, emo, Britlad, Cockery, indie, a little bit recent vintage retro mixed up, so that there is also shavings of Savile Row, swing, nerd, hipster, boyband; that he is golden in how he can look all at once Elvis, teddy, punky, Kinky, art school, modernist, Roxy, two tone, long mac monochrome, Smithy, Beastie, Parklifey, cartoony, Streets-wise; classic in how his fragile, awkward, eager, indifferent frame can absorb a whole convention-busting history of looks, illusions, street styles, fashion statements, dress codes and subcultures, spanning the spectrum of change from 1950-ish to 2000-ish, reflecting the fermentation and fragmentation of taste, sexuality and identity. He is, perhaps, blank enough and yet specific and committed enough to become a living body blur of all those edited changes and surges in fashion; a stubborn, solo-gathering of those moments in pop history that proposed new ways of seeing, hearing and feeling, which have led to where we are now.

On a wall in the grubby basement area of this building, which is generally used as a bar but today as a changing room and general small-talk area, there are some photographs pinned up of the kind of stars and heroes from the past that it is said he resembles and rekindles, or whose energy and attitude he inherits. I’m told it is a mood board representing the ideal intoxicating image of self-involved disaffection that is the goal of today’s shoot – estimating where the redheaded pale-faced individual belongs in the outsider scheme of things, amongst all those outlaws, poets, provocateurs, dreamers, pin-ups, voices of generations, faces, rebels, actors and loners.

“UP TO ABOUT EIGHT I HAD NO FRIENDS AND MY MUM PUT ME INTO CHILD MODELLING AS A KID. SHE SOLD ME AND MY BROTHER, AND KEPT THE MONEY; WE WERE LIKE THE TWO ODD REDHEAD KIDS IN THE 90S SELLING GEAR AND I GOT A LOT OF STICK FOR THAT. I HAD FEWER AND FEWER FRIENDS. THEN I WENT TO SECONDARY SCHOOL AND DIDN’T LIKE THAT SO DROPPED OUT AND LITERALLY SPENT FOUR YEARS ON MY OWN IN A ROOM, STUCK IN THE HOUSE WITH MY BROTHER – MAKING MUSIC, DRAWING, WATCHING TV, LISTENING TO MUSIC. I GOT MY FIRST LAPTOP AT THE AGE OF 15 AND THAT KEPT ME INSIDE EVEN MORE. I REMEMBER A WHOLE SUMMER JUST SAT INSIDE WITH MY BROTHER, IT WAS A REALLY GOOD TIME. WE DIDN’T HAVE ANY FRIENDS AND WE WERE BOTH EMBARRASSED THAT WE DIDN’T HAVE ANY FRIENDS, AND MY MUM WAS LIKE, ‘WHY DON’T YOU HAVE ANY FRIENDS?’ BUT WE JUST BONDED SO MUCH AND DEVELOPED CONNECTIONS, AND HE SHOWED ME SO MUCH – IT WAS A GREAT PERIOD OF LEARNING THINGS. I DROPPED OUT OF SCHOOL COMPLETELY AT 16 AND IT WAS LIKE DROPPING INTO THIS VAST OCEAN THAT WENT ON FOREVER, AND YOU COULD SO EASILY GET LOST AND I WAS LIKE, ‘HOW AM I GOING TO FLOAT? HOW WILL I EVER BE SEEN?’”

I was determined that in this piece I would not mention any names of those musicians, actors, artists, influencers, legends and role models generally referred to when the subject of this piece is written about – to the extent of also not even mentioning the name of the individual, leaving you to work it out, because it seems to me that the mystery of a personality, of a performer, perhaps even a genius, is spoilt by all the repetitive information and rule-following analysis instantly shared and obediently received in the increasingly available and flattened world.

It seems absurd to demonstrate that here is a new face, a new genius, when he is so encased in precedent; on the other hand, perhaps that is his originality, the originality of noting, connecting, collaborating, creating and distributing across a tense, threatened reality that is torn between the virtual and the physical, the familiar and the scary. The original has become the one who best synthesises and repackages historic forms and forces in reverent and irreverent ways. Perhaps it was always this way: the putting together of things you like as you grow up, the things that make you want to do it as well, in a way that creates the energetically brand new; a way of understanding what’s around you, a hybrid of unlikely influences that draw and sculpt an audience who sense something in this hybrid. It’s just that now the element of surprise has been taken away and there is so much out there to absorb and so many people other than the creative artist aware of what has gone before. It is impossible to arrive with as much sensational suddenness, even anarchic abruptness, as the original pop and punk stars, however marvellous, however astonishing the agility of mixing sound, space, city, personal experience, lust, annoyance.

For now, it seems, the individual being photographed dresses up in the rebel costumes of yesterday, appropriates the poses and gestures of previous heroes and mavericks, acts as though the times are vinyl, whilst exploiting the fluid, melting zones of the internet and produces a soundtrack to new ways of inhabiting a city, the street where you live, the places where you go to work and play, inside an expanding online world, a soundtrack that could only be made today and yet contains no sound or rhythm or texture that has not already existed.

The baby-faced individual, with the look of a remade and reshaped 20th century where the promise of youth took over, is the sound of a mutant post-time London as it keeps its changing shape and shatters into a million pieces. The nervy, super-sure, eternal teenager individual is negotiating a way through this dense thicket of action and reaction, event and comment, and standing out from the crowd through sheer nerve and a loyalty to the idea of The Star, the special spokesperson placed by themselves and others on a high pedestal above the roaming, knowing crowd. He’s born too late, after a time when he would have made more sense, and too early, with a way of thinking through things that might be more relevant once this attraction to the recent past has been shaken off once and for all.

Whatever happens to music, to fashion, to the idea of being young and restless and estranged, of growing up in the real city, in the other unreal cities of the internet, our basic need for comfort, engagement and encouragement will remain more or less the same, and require novel, flexible forms of creative productivity and a maintenance of the idea that music does not necessarily change the world and definitely does not solve social problems but transmits vital underclass and underdog rage where it belongs – at the rich and powerful – and challenges listeners to look for strength in themselves. Even, and perhaps especially, in a world that more and more noticeably makes itself up as it goes on, creating fictions by the second, there is more than ever a need for those who make-believe, who lead the way when it comes to self-invention, re-invention and whatever comes next. We will retain our faith in the individual who stands out amongst all those individuals who can also now create and distribute, the individual who makes things just like everyone else can make things but with something else, something that remains magical because only a very few can actually do it.

The rangy, preoccupied 19-year-old Archy Marshall inevitably known by other names and personas – including King Krule, a fond nod to 1957 Elvis Presley and 1981 Kid Creole as livewire partners in song and dance – has just spent a few hours having his photograph taken. He has a teenage past as the precocious noise wonder Zoo Kid, a name he wants to shake off so that by the time he is 20 next August he’s broken free of childlike concerns and not as minor league kitsch as his mentor Creole became. He does other things that require other DJ monikers and comic pseudonyms, drifting into other backyards and slipping along murky border areas, but it’s as King Krule that he heads for the mainstream, as if he can rough it up, melt all that plastic and blast through all that girly-whirly strip hop.

He seems less bothered about the mood board, the pictures on a wall of the likes of Rotten, Dury and Strummer and various fixed icons of challenging, greased back, quiff forward cool than I do. The tone of our interview is established once I have got worked up, like an ageing punk, at the very idea of attempting to style a picture of defiance by referring to previous models, and Archy – like a self-possessed teenage consumer, boaster and collagist – has vaguely shrugged his shoulders and mumbled something non-committal that I am not immediately sure is humble, complacent or actually truly defiant.

There is an invisible screen between us made up of all the screens that have emerged in the world since I was 19 in 1976. We have a history of music, pop culture and leisure entertainment in common and can make a connection through various composers, performers, films, artists and celebrities, and to some extent we speak the same language, except his is filtered through teenage years spent in tough, agitated South London immersed in history and entertainment as it located itself online and mine is filtered through teenage years spent south of Manchester immersed in history and entertainment as it located itself through Top of the Pops, the early 1970s NME and John Peel. Both of us seeking salvation and respite from dismal surroundings, both finding help through the tragedy and comedy of the Sex Pistols or the space and vibration of Jimi Hendrix or the optimistic fact that there is always some other music to come because you haven’t discovered it yet – or it’s about to be made.

The screen between us often means I ask a question and he answers another one altogether – either because he has misheard me, doesn’t understand me or just thinks I am missing the point altogether, not wised-up enough to get the joke or to understand how there is no longer any such thing as the past or sentimental nostalgia for it, just one extending platform into a continual present where time collapses and where everything feeds into, ready to be manipulated and transformed into new material. He tolerates what for him must be a very strange and naïve view of time when one thing followed the next in a certain linear order and years and genres were separated by natural order, one for whom Johnny Rotten, Joy Division, Suicide and Burial happened in real time not in a virtual abstract time as if at the same swinging, sampling time as Cab Calloway, Frank Sinatra, Eddie Cochran, Charlie Mingus, Lee Scratch Perry, Tricky and Madlib, a time where Charles Dickens, Andy Warhol and Spike Jonze tell their stories and invent their gossip in the same terrain.

When he was growing up, he says – as though it was only happening to him and he was at the centre of time and the universe and it was all for him to take, work out and work on – “there were all these cats: Johnny Rotten, you get into that, and Jimi Hendrix, I’m eight and I’m getting into that, he was the man for me, perfect for a kid to follow; he was just the coolest cat and I looked at his art work and listened to the music and I wanted to know how it all happened, how it was made. Then there was Ian Curtis and Joy Division and I guess I started to become fascinated with tragic characters and crazy stories, that was where it all seemed to be the most exciting – the rockabilly cats of the 50s who by the end of the decade were dead or in the army or in jail or ruined. Ian Dury… I couldn’t resist the whole idea of how he looked and moved and what came out of his mouth. I started to love the shapes my mouth made because of the words I said. I became interested in dark things; it suited me much more than pretending I was happy all the time. Pop was so plastic when I was growing up, it made no sense to me and yet there were all these tragedies out there, amazing stories and characters giving everything for the sake of making music and singing songs. I started to find the rebels. It all seemed more real than making up rhymes just because they made you feel good.”

He talks in a distracted don’t-look-at-me drowsy jazz-mumble, where people are “cats” and they deal with “shit, man”, where he’ll finish rolling a joint before getting to the point and then lose his thread, injected with a suppressed distant hint of genteel well-spoken English; a plummy Archibald that isn’t too moot in a world where he must be a bent-out-of-shape underworld groove prince before he can become a holy moly king of the world. It’s a sound that has arrived naturally out of arty, liberal South London, family, school or lack of school, of hours spent staring at screens longing to connect and general exposure to theatrically incoherent rebels from Brando and Miles to Snoop and Mathers, or has been self-consciously developed to passively suit his current persona as exotic, dedicated and tormented wunderkind and bizarre, wonderfully sullen dub-crooner discreetly pissed off at being constantly called a kid. He aims to talk like he may well have hung out with some of his intense and introverted heroes – from Chet Baker to James Chance, Gene Vincent to Talib Kweli – and learnt the protective promotional art of keeping yourself to yourself whilst concentrating on the only thing that really matters and explains who you are – your music, man.

He says – like it can be so simple, like he’s getting to all this first, as fresh as a Presley, as first-thought as a 1962 Beatle, as propulsive as a Pistol – “I just want to play and get respect for being the guy who played that music, who performed like that and people say, ‘Yeah, that makes sense’. Why am I seen as being different? I don’t know. I just have my own level of integrity and the emotions I need to express seem to connect with others and there is a connection, which means something must be happening.”

He has learnt how to give the impression of having so much inside that it will only come out in a rush or not at all. He plays the part well – the rough mix of eternal, naughty teenager, hip hop humourist, street urchin, poundshop dandy, scruff clairvoyant, social brat, shrewd hustler, troubled soul, moody scoundrel, considerate listener, KFC existentialist, soberly ambitious artist, mummy’s boy, loop digga, pose looter, the gloomy boyish fantasist looking for a little control over the universe, nattily balanced midway between diva and hoodlum, sweet showbiz kid with polished edge and blasé bohemian, insouciant sourpussed outcast and endearing male equivalent of the girl-next-door craftily persuading you to lower your guard. He acts like he doesn’t give a damn, which is the classic double bluff of someone who really, really cares so much, or he has worked out that this is what is expected of a potential next big thing. He has studied, formally and informally, what it takes to be the kind of troubled, intriguing outsider artist he has set his heart on becoming, one that combines the dead set sure-of-himself with the distracted leave-me-alone remoteness – and has achieved the equivalent of a first class degree.

During our conversation, one uses slang that marks him out as a character from a film based on his own life, one uses language that marks him out as a journalist who interviewed Josef K, Subway Sect and Orange Juice 34 years ago and cannot help but notice the similarities between those bony pop-shocked “cats” and their way with a scratchy stolen riff and a literate lovelorn rhyme, a grabbed catchy melody and a trapped hounded look. Amazingly, a conversation ensues just about within reason. Occasionally, he gives an answer that is in the zone of actually making sense in terms of what the question was but mostly he’s in his own world and I’m in my own world, and we’re both in our own dream.

He’s a London boy, you can see it in the eyes, face and poses, the way he low-key enters a room and leaves it, and glances at some things, stares at others, bothered, pissed off, at home, adrift. But more than that, he is a child of the internet – the technology, connectedness and mind-bending advances in the gathering and saturating of the trivial and the magnificent moving along as fast as he has moved from super keen eight-year-old to wideeyed 13-year-old, following his brother into art, the painted world and the painted word, into the tech world, changing shape and dimension and capability as much as his mind and body. One thing is feeding into the other. In his lifetime, the internet has gone from being horse and carriage to shooting for the moon.

“IT’S FUCKING AMAZING, MAN, IT’S GOT EVERYTHING IF YOU JUST WANT TO GO AND FIND IT. IT’S GOT PARANOIA, IT’S FULL OF INSPIRATION, IT WAS INSANE GROWING UP AND WHEN WE WENT FROM DIAL-UP TO WIRELESS, MAN, IT WAS INCREDIBLE. I REMEMBER THE FIRST TIME I DISCOVERED MYSPACE, FINDING OUT ABOUT ALL THESE SCENES IN LONDON AND ASPIRING SO MUCH TO BE A PART OF THEM. THAT WAS MY FIRST GOAL AS A 13-YEAR-OLD – TO GET ON MYSPACE. SOMEHOW I JUST HAD TO GET MY MUSIC ONTO MY BROTHER’S COMPUTER SO I COULD GET IT ON MYSPACE. AND SOMEHOW I MANAGED IT AND I STARTED TO SELL MIXTAPES AT THIS SCHOOL I WAS GOING TO, WHICH WAS MORE OF A YOUTH OFFENDER PLACE, AND I STARTED TO PLAY PUBS AND SOCIAL CLUBS EVERY WEEKEND, DOING MY OWN FLYERS. WHEN PEOPLE ASK ME HOW IT HAS HAPPENED FOR ME AND WHY I HAVE BEEN NOTICED, I SAY, ‘YOU HAVE TO GET OUT THERE AND PLAY TO PEOPLE, HOWEVER SMALL THE PLACE, YOU HAVE TO GET OUT THERE AND SEE PEOPLE BOUNCE UP AND DOWN IN FRONT OF YOU, SEE THE LOOK IN THEIR EYES, WHICH MEANS THEY CAN SEE THE LOOK IN YOUR EYES.’”

You must move from the virtual to the solid.

“YES, THE VIRTUAL WAS TO GET PEOPLE TO KNOW ABOUT ME, TO NOTICE ME, AND THEN THE POINT WAS TO PLAY LIVE, WORK WITH CATS.”

London kid, online animal, Kafka fan, reader of three books by Dickens and a swooning A Clockwork Orange obsessive… but then this thing that nags at me all the time we talk, this masked hint of the showbiz kid trained to be adorable and pliable however much interested in the dark side and the maverick and difficult mind. Maybe I’m over-reading it but there’s this interference at the edges of his moochiness that he is just another self-important kid who came of age when the idea of a career in show business was actually an option.

After being kicked out of various conventional schools and drifting in and out of secure units and youth offender centres, he ended up at Croydon’s BRIT School for Performing Arts and Technology, which has produced a number of highly selfpossessed and knowing, if largely sanitised, pop acts including Amy Winehouse, Jessie J, Adele and Leona Lewis, and perky, hollow rebel-lite groups like Rizzle Kicks and The Kooks. So is he really just the showbiz kid at a time when the modern showbiz kid is styled as being indie, hipster, sophisticated, rough and ready? He doesn’t flinch when I mention this, and naturally, gives nothing away, either not understanding what I’m talking about because he has absolutely no idea or knowing only too well and already well-briefed.

“NOT AT ALL, MAN. YOU GO THERE NOW AND YOU DO GET A LOT OF KIDS WHO ARE THERE JUST TO GET FAMOUS. I WENT THERE ABOUT 2008, A COUPLE OF YEARS AFTER PEOPLE WERE EMERGING FROM THERE INTO THE MAINSTREAM – KATE NASH, THE FEELING, LILY ALLEN – AND SO I WAS ALWAYS AWARE THAT FOR SOME REASON THESE ARTISTS GOT CHURNED OUT OF THERE. BUT THE ONLY TIME I FELT THEY WERE PUTTING ANYTHING SHOW BUSINESS ON ME WAS AFTER I GOT MY FIRST EVER WRITE UP IN THE GUARDIAN WHEN I WAS 16 STUDYING ART AND HISTORY. I HAD PUT OUT MY FIRST SINGLE – THINGS WERE ALREADY HAPPENING BUSINESS-WISE, AT LEAST, AND I’D MADE THIS RECORD, AND I WENT TO SCHOOL THE DAY AFTER THE GUARDIAN WRITE UP AND I GOT CALLED IN FOR A MEETING. THEY WERE LIKE, ‘OH, WE CAN HELP YOU WITH WRITE UPS.’ I WAS LIKE, ‘I’M OK MAN. I KNOW WHAT I’M DOING.’ THAT WAS THE ONLY SIGN OF SHOWBIZ I FELT WHILE I WAS THERE. OTHERWISE THEY WERE JUST TRYING TO KEEP ME IN SCHOOL BECAUSE I WAS EXCLUDED FOUR OR FIVE TIMES. WHEN I STARTED GOING THERE I HAD JUST COME OUT OF THESE CENTRES FOR YOUTH OFFENDERS AND I FELT BECAUSE OF THAT THEY PICKED ON ME MORE, IT WAS LIKE ANYTHING I DID WRONG THEY’D BE LIKE BAM! – OUT OF THE LESSON, BANNED FOR A WEEK. THEY WERE STRICT ON ME FOR A LONG TIME AND I WOULD FIGHT AGAINST THAT, LIKE YOU DO, AND IN THE END THEY PUNISHED ME A LOT OF THE TIME AND SOMETIMES I DESERVED IT… IN THE END, I GOT A GOOD EDUCATION THERE; I STARTED TO LOVE HISTORY AND I GOT INTERESTED IN THE NATURE OF VARIOUS ERAS AND THE CONNECTION BETWEEN THEM, THE CULTURE THAT FORMS BECAUSE OF THE TIMES, THE 1920S AND THE JAZZ AGE AND THEN THE DEPRESSED 30S AND THE BLUES.”

Where does he think we are now? A note of reason is smuggled through the protective mumble. “It’s a very, very interesting time, post 9-11, post 7-7, all the changes because of the internet and China making Europe the Grandad that’s about to die, and then America will be the Grandad, and China and South America will take over.”

Should music directly reflect these changes, should music be influenced by it all?

“IT DOESN’T NEED TO MAKE A DIRECT RESPONSE TO ANYTHING, IT JUST NEEDS TO BE HAPPENING DURING THESE TIMES – AND I WANT IT TO BE PHYSICAL, MAN, I WANT MUSIC, ART, THEATRE, DANCING, FILM TO BE MORE PHYSICAL IN THE NEXT FEW YEARS. WITH THE INTERNET, EVERYONE CAN DO ANYTHING AND GET IT OUT THERE, WE’RE SITTING DOWN ALL THE TIME PLAYING WITH OUR PHONES BUT WE’RE LOSING THE PHYSICALITY, THE BEING IN A SWEATY ROOM WITH PEOPLE AND SEEING PEOPLE EYE TO EYE AND BOUNCING UP AND DOWN TOGETHER. WHEN I GO OUT IN LONDON YOU GET THE FEELING PEOPLE ARE BEGINNING TO FORGET HOW TO BE WITH EACH OTHER AND THERE IS A LOT OF TENSION AT THE SAME TIME AS THERE IS A LOT OF COMFORT, SO THAT A REVOLUTION MAKES NO SENSE, OR IF IT BEGINS TO HAPPEN IT SOON BECOMES JUST SOMETHING ELSE YOU HATE.”

He says, as though pure willpower can remove all obstacles, as though he has a manifesto like the punks, a calling, a natural romantic need to reject the compromised adult world even if that’s now where most of the influence comes from, a need to be part of a new scene: “I want to have a space that will hopefully influence people to have their own spaces, where you can dance, hear music, make music and art, a space that can be for parties and gigs, not just a place where you go to get fucked out of your head but a place, my place, you can go to for free and do things, make things. It could all die out, physicality, and it mustn’t; people should pick up instruments, not go straight into production, a mic and pressing play, I want it to be a performance, to see, to do, to change… I don’t know what it will be like but I know it’s going to be good, and I feel positive about the future because I am showing how it can be done.” Maybe it’s that he believes he should have a manifesto because that’s the way it used to work, as though we’re still in a world where there are 6,000-word articles written about rock musicians because that’s where you look for a sign of something, a guidance, a realistic clue about what’s happening and why.

Where I am convinced Marshall is maybe not playing the part but is the part is when he free forms about music, taking the conversation where he wants it to go, not worried about the glut of music that drowns out music, the idea that pop music is now merely a soundtrack to a publicity campaign, that to make even the most avant garde of pop music is the new status quo, as revolutionary as a beanie, not something a youngster with an interesting mind should be doing. He talks about all that music he has heard that turned his head and heart, turned him on and turned into his very own music, packed with temptations and vulnerabilities. Talk where he can slip from Ravel to Madlib, Debussy to Dilla, Cochran to Sly Stone and praise the lord for the abstract route to his dubbed-in crazed-up off-kilter funkabilly sound on his first album, 6 Feet Beneath the Moon, released on his 19th birthday, all that street and soul that came from Fela Kuti and James Chance and the Contortions, from Herbie Hancock and Gang of Four, from A Certain Ratio and Donny Hathaway. Suddenly, after a little jerky riff on the sublime, timeless patience of Erik Satie, where carefully placed and paused rising and falling musical notes can cause intense reality-scrambling hallucination, he’s talking about the transcendently suave Bill Evans, the pianist on Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, whose own career contained hours and hours of making music as if music was where you found the essentially human, the most intense summary of what it is to be human, what will last of the human if the machines take over and reduce us to bits of dust.

“OF ALL THE MUSICIANS I HAVE LISTENED TO, BILL EVANS IS THE MAIN MAN FOR ME. I CAN LISTEN TO HIM FOR HOURS, IT DOESN’T MATTER WHAT ALBUM, WHAT TRACK. I GUESS IT’S ANOTHER FASCINATION WITH THE DARK SIDE – HE WAS A HEROIN ADDICT, BUT KEPT IT QUIET, WEARS A SUIT, HE WAS FUELLED BY HEROIN BUT HE WAS CLASSICALLY TRAINED AND HE MAKES THIS ALBUM WITH CHET BAKER, AND IT’S VERY SPOOKY. HE’S A MINIMALIST, BUT OBVIOUSLY NOT – HE CAPTURES SILENCE SO BRILLIANTLY, AND I REALLY RESPECT THAT. AND MY LIFE WAS CHANGED WHEN I READ THE NOTES HE WROTE TO KIND OF BLUE.”

The mood changes a little, there’s a few more thoughts about Miles Davis and the way his music was always changing, the way he wants his own music to be always changing, and maturing, a riddle he’s always working out, and eyes-down Archy sighs as if this is the only thing he wants to say in this interview because it says it all and his mouth makes a great shape as he says it: “Miles had a beautiful face.”

The talent, the individual, the beaten kid leaves the building, glad the photos are done and the interview is finally over. He can get elevated now, disappearing into the city; it’s cold out there, and mostly dark, he’s taking a back route, just south of back-in-the-day, looking for a wall to scrawl his name on, a hall to throw a beat into, a scene to latch onto, the next street, the next sound, mixed with the next sound, in the shadow of online and into the city, where he is no one special, just someone else trying to work everything out and someone for real to watch – that is, if there is still such a thing as being special, man.