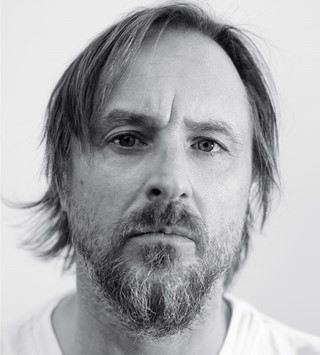

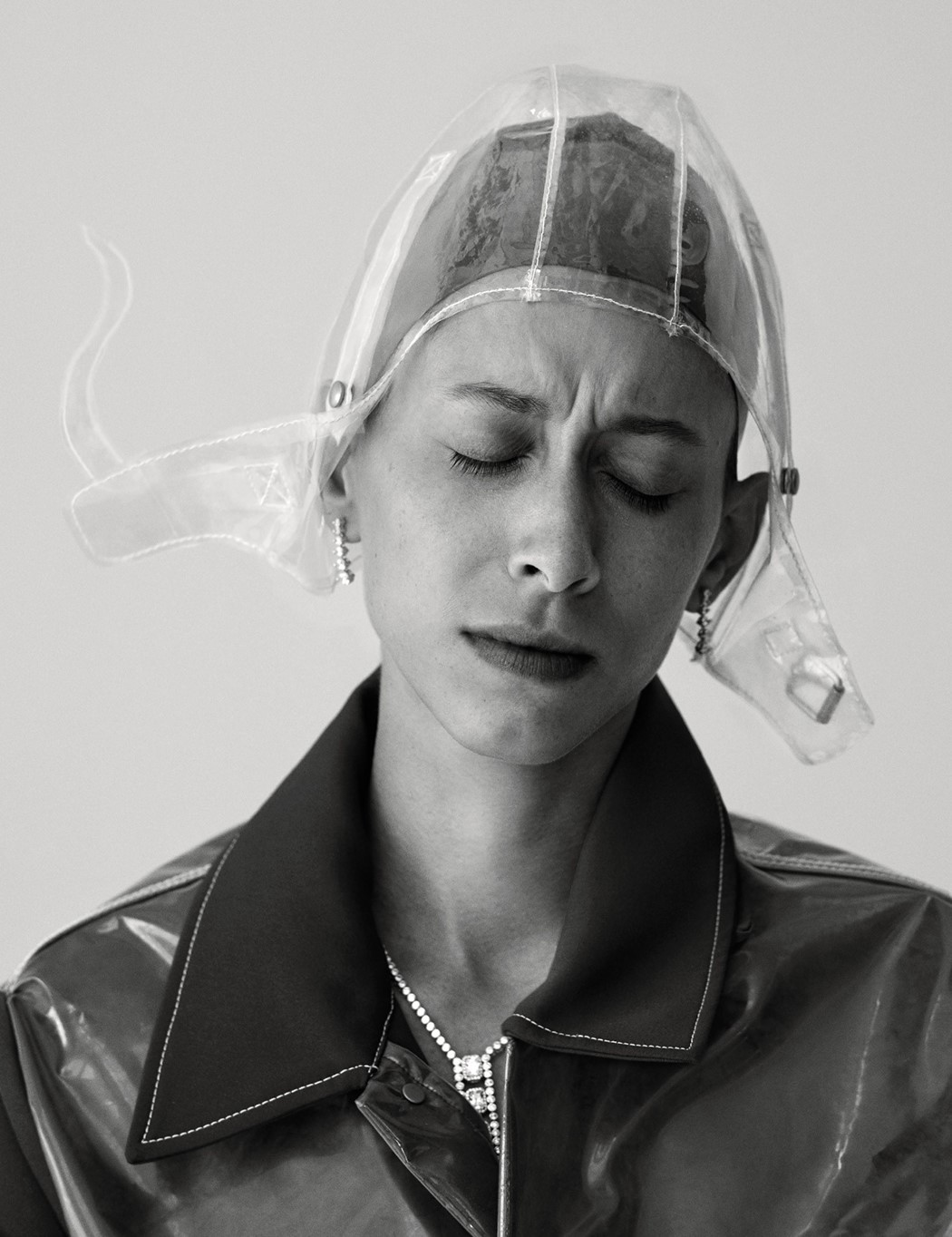

John Galliano Speaks to Alexander Fury on Gender and Fashion

- TextAlexander Fury

- PhotographyEthan James Green

- StylingEllie Grace Cumming

At the helm of Maison Margiela, John Galliano is conjuring a spectacular new vision of genderless glamour. In an exclusive interview, fashion’s great virtuoso muses on his enduring love affair with modernity, romanticism and reinvention

Taken from the A/W18 ‘Romance and Ritual’ issue of Another Man:

For the past 18 years, John Galliano has spent most of July and August in a modest house on the coast of Saint-Tropez. The house is owned by a man who made a fortune from marketing duty-free alcohol miniatures; the only other home in the vicinity is occupied by Alix, Princess Napoléon, ‘Empress of the French’ in pretence, in her twilight years. It’s fairly inaccessible by land, especially at the peak of summer, when traffic snakes along the coastal slaloms – instead, a boat buffets travellers from Nice across the Côte d’Azur to a rock jetty, past the kind of pleasure cruisers colloquially referred to as ‘Gin Palaces’, lazily floating, filled with billionaires and bullion and Bollinger and collagen. It is the French Riviera after all. It sounds romantic, but in actual fact the boat that ferries you to John Galliano is somewhat industrial, a high-powered inflatable number called a Zodiac that smashes through the surf at near-literal breakneck speed. It’s hard work.

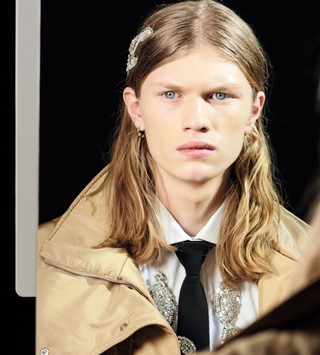

That’s a fitting metaphor for the work of Galliano, particularly his latest incarnation helming Maison Margiela, where his intrinsic sense of romance has melded with something harder and tougher, something rougher, to create a new vocabulary of design for both himself and the house. In January, he debuted his first menswear ideas for Margiela – he had previously been involved, he asserts, but in a looser, more abstract way, guiding an appropriately anonymous group of designers. Since the founder’s official departure in 2008, the results hadn’t gelled, for either Margiela nor its audience. The Autumn/Winter 2018 collection was Galliano’s first attempt at elucidating that frequently-elusive Margiela man – and rather than try to segregate him from the identity of the womenswear, Galliano cleverly melded the two together. The obsessions of Galliano’s collections for women merged with silhouettes of masculinity – abstract notions of glamour, like slithery bias-cut satin spliced into a two-piece tuxedo instead of an evening dress; thumped-up, bricolage sneakers below sloppy wide-shoulder coating; the idea of the décortiqué, literally translating to peeled or shelled (as in, shelling a crab) and denoting garments dissected to their bare bones, rendering the functional decorative and lending an ornament to the utilitarian.

There was, throughout, a synergy to the offering – which is what Galliano declared the giant, Bird’s Custard-yellow symbol painted across the catwalk stood for, too. Although the synergy was left vague – between men and women, between Margiela and Galliano, between these clothes and the outside world. Or potentially, all of the above. “That collection in concept was similar to the first collection – Artisanal – I did in London,” says Galliano, slowly. It’s six months later – he’s shown three collections for women and another menswear since then, so is scrolling through images of the clothes on an iPad as digital age aide memoire. “So it was a collection of intent. We were trying to try a little bit of this – some tailoring, some more casual, one bias-cut suit. I was building blocks, to get some feedback, some reaction.”

“That collection in concept was similar to the first collection – Artisanal – I did in London. So it was a collection of intent. We were trying to try a little bit of this – some tailoring, some more casual, one bias-cut suit. I was building blocks, to get some feedback, some reaction” – John Galliano

The reaction was strong – in a period of menswear upheavals, of departures and rehires and the inevitable anticipation such turmoil brings, Galliano’s Margiela debut leapt to the head of the pack as a leading statement, something bold and brave and fresh added to the conversation. “I think it needed to be established at that season,” Galliano reasons. “Also with the changing landscape of menswear – with all the exciting things that were happening – it was like, ‘Oh my god John, what are you going to do?’” he laughs riotously, his head cracking back from the jaw. The intonation in Galliano’s sentences swirl, from considered and patrician, swelled out by the crisp rounded vowels of received pronunciation, to a cockney drawl that sketches out Galliano’s childhood in Streatham, South London. He was born Juan Carlos Antonio Galliano-Guillén in Gibraltar but moved to London with his two sisters when he was six. His dad was a plumber, his mother danced flamenco on the kitchen table-tops. The sentence ends on that London drawl, a plaintive wail tinged with mirth. What was Galliano going to do for this, his Margiela menswear debut?

It feels strange to call any Galliano collection a debut – Galliano has been at Margiela since October 2014. He’s also 57, a Commander of the British Empire, a reference-point for generations of talent from the late 80s onwards. Something of an institution in and of himself. He’s John Galliano! But in Saint-Tropez, he’s JG – his own nomenclature, perhaps adopted during the wake of his dismissal from his eponymous label and the house of Christian Dior in 2011 following a racist outburst in a Parisian bar. That episode was a very visible result of a then-clandestine but now well-documented addiction to drugs and alcohol that had spanned the majority of Galliano’s career: the immediate aftermath of it was a difficult period of rehabilitation, public penitence and a tabloid lashing, when the name Galliano closed doors rather than opened them. Maybe it was then that anonymity (very Margiela) began to seem enticing. Seven years later, in Saint-Tropez, Galliano looks well, fresh and relaxed – despite that baggage, almost unremarkably so, in a way that a designer would to journalists accustomed to seeing them wound tight between fittings in the days leading up to their show. Unlike others, Galliano, famously, doesn’t see press backstage at his Margiela shows and refuses to bow at the end – a trait he shares with Martin himself. He does, however, give interviews. Which is how we wind up on the Riviera, curled up in Galliano’s adopted living room, talking about the meaninglessness of menswear.

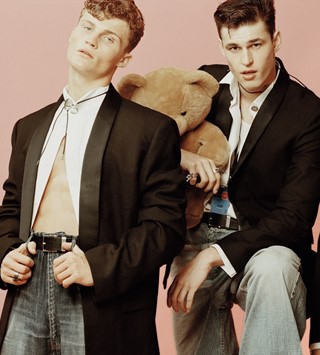

“More than just which way to go, it was to help me define who is the Margiela man,” Galliano says, of that first collection. Then he stops. “I say that and I take a breath as well,” he states – smiling – like a stage direction. “Because I don’t feel comfortable saying that. Today… Just calling it menswear and women’s made me kind of blanche a bit.” His sophomore offering for Margiela menswear (sorry) was staged in June in the Margiela atelier as a tiny Artisanal show, the name given to the line’s offerings for haute couture which are made-to-measure, one-off and traditionally only for women. The latest of those he dubbed ‘Nomadic Glamour’: rather than an elegiac Galliano voyage through space and time, there were ideas of clothes travelling around the body – “So a skirt became a cape and then, within it, I cut the memory of jacket,” is how Galliano describes it. The actual garment in question was the opening look of the show, a coral foam skirt migrated to the shoulders, head poking through the waistband, with the shape of a single-breasted jacket spliced out and peeled away, like a Vesalius drawing – or a frog in a high school biology class. There was, actually, no reason this couldn’t be worn by a man too. “Quickly just think of a very testosterone-driven image of Clint Eastwood in a poncho. Just to aquarelle the look,” Galliano says, expressively. “It just made sense. That hey, this could be really fun, and I don’t know if we’re going to be successful or not. But the idea is quite unique. The idea that a cape, certain items, could easily work on either-or.”

Galliano has frequently called haute couture the ‘parfum’ that infuses through the rest of the house’s creations, the way an essence is literally watered-down, to create a variation slightly less intense but still powerful and intoxicating. Another debut, this was the first time an entire Artisanal collection had been offered for men – at Margiela, by Galliano, or indeed in the realms of haute couture at all (although several houses, most notably Gaultier Paris and Dior when helmed by Galliano, have offered couture clothing for men, but only accompanying designs for women). “At the most extreme, I wanted to establish how Artisanal men could inspire, so we put the spotlight on that this season,” reasons Galliano.

“It would just be too easy to have the boys wearing girls and the girls wearing boys. That’s not what it is today. Find your own masculinity. Find your own femme. Define it yourself. And that’s what they’re doing today, and I’m so there” – John Galliano

Made-to-measure haute couture may be inspiring, but it doesn’t pay the bills – or fill the stores. “We still did the ready-to-wear,” allows Galliano. “It’s still there, and we sold it. Some of the silhouettes were echoed in the Artisanal man, but it had its own inspiration, etcetera, etcetera. And that I will show with the women’s in September, which was my aversion to – ” Galliano shrieks, theatrically, to the cheap seats in the back “ – menswear! Which is un peu démodé. So it’ll be a mix of the two. Un-binary, genderless. And that’s the challenge.” Just don’t call it co-ed, or mixed. “It would just be too easy to have the boys wearing girls and the girls wearing boys,” says Galliano thoughtfully. “That’s not what it is today. Find your own masculinity. Find your own femme. Define it yourself. And that’s what they’re doing today, and I’m so there.” He smiles wide. “Because I grew up with all that but it was not easy. You got a good beating back then.”

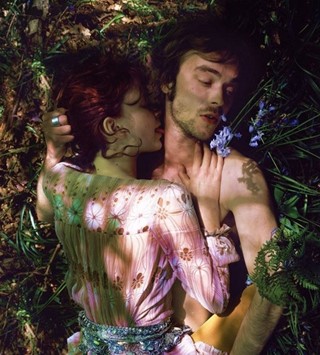

John Galliano has played games with gender before. Indeed, as difficult as it is for the short-term memory of fashion to reconcile the somewhat precious, couture-driven output of the prior stage of his career with the identity he is forging for Margiela, it has always been there, bubbling under the surface. In the 1980s, when Galliano exploded onto the scene following his 1984 Bachelor of Arts graduation collection, titled Les Incroyables and dedicated to the provocative, politicised aristocratic rebels of the Terror of the 1790s, his billowing, histrionic clothes – ruffled organdie blouses, puckered brocade waistcoats, sweeping frock-coats – were worn by models of both sexes, pouting and preening, reflections of the crucible of a hedonistic London club scene latterly dubbed ‘New Romantics’.

Galliano still finds the idea – and that period – inspiring today. Not to replicate the clothes, but to mirror the energy, the emotion and the experimentation. “Shirts were worn as skirts. Do you remember?” Galliano declares. “You button in front and tie the sleeves. I remember doing the Malcolm McLaren cover with Amanda” – now Harlech, then Grieve, Galliano’s first stylist and creative collaborator for 12 years. They met after Galliano’s graduation and worked together to style the artwork for McLaren’s 1984 album Fans. “And Malcolm threw an old v-neck Shetland sweater at me and said ‘Do something with that – they say you’re a genius.’” Galliano’s voice notches up an octave; the Streatham comes out. “And I’m like: alright bitch, I’ll do something with it! And I asked the model to step into it, so the v was like to here,” Galliano scissors his own crotch, smirking. “And we tied the thing around. Amanda was like, ‘Oh, it’s fab! It’s a bustle!’ Do you know what I mean? That v-neck became a skirt!” A final octave. “This territory that was fun and you can probably tell from my voice I’m still quite excited by it. Naïve? More naïve isn’t it. Which is quite fab.”

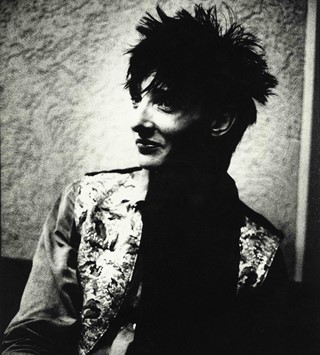

Those were the sort of clothes that provoked those beatings in the street, just as their 18th-century antecedents did. Galliano himself didn’t just design them: an ardent clubber, he wore them, too, living the fantasy – and they were bought by men and women alike, something oddly geared to a current mood of malleable, kinetic gender identity. Galliano has designed traditionally-defined menswear before – between 2004 and 2011, there was a Galliano Hommes collection presented biannually in Paris. The final own-label show he took a bow at was his winter 2011 menswear outing dedicated to Rudolf Nureyev: Galliano was dressed in tapestry sarouel trousers, a twine-bound fur coat, a kubanka and several tassels that seemed tugged down from the curtains of the Winter Palace. It was, as they say, a look.

“I remember doing the Malcolm McLaren cover with Amanda [Harlech]. And Malcolm threw an old v-neck Shetland sweater at me and said ‘Do something with that – they say you’re a genius.’ And I’m like: alright bitch, I’ll do something with it! – John Galliano

Those ‘looks’ were seen as a key reflection of whatever creative inspiration had taken root – if Galliano was transforming his models into nomadic warriors, or cabaret floozies, or sweat-soaked flamenco dancers – male or female – a bit would inevitably rub off on him too, like make-up on the dance floor, rubbing off someone else’s face onto yours. So much so, indeed, that when the Galliano Hommes line was first presented, it was very much seen as an extension of the multiplicitous, multifaceted identities Galliano had been proffering for years. Today, Galliano is lower-key – in shorts, Chuck Taylors, an enviously holey Nirvana ‘Corporate Rock Whores’ t-shirt. He’s off-duty. The Margiela man – or rather, Margiela person – Galliano is creating isn’t himself. And the expansion into menswear certainly isn’t about dressing himself. “It is true that I would express myself because I was living the part of the creator,” says Galliano, when this is mentioned. “But I had to consciously stop that. Because of the work I had done on the inside. If it wasn’t reflected on the outside people… maybe thought that I hadn’t done the work. I noticed that. So I started to wear suits when I went out or had lunch with people. Almost that anonymity I quite liked. I quite liked not being judged like that. I mean the suits were faultless! Savile Row! But I quite liked that anonymity. I’m a bit more cautious of what I look like when I’m out there now.”

Galliano punctuates that with fragments of laughter, a wicked whiplash of that Streatham accent on the word ‘faultless’. But he’s alluding to his public breakdown in 2011, which resulted in his departure from the Dior and Galliano houses and a period coming clean in the Meadows rehabilitation facility in Arizona. His conversation is still keyed to the language of psychotherapy and recovery – that inside/outside work, which is never entirely complete. He describes social media as “addictive – the likes, loves”. He once told me it had taught him the subtle difference between being famous and infamous.

Galliano’s fame made the idea of him helming the famously faceless Maison Margiela difficult for many to swallow, in the first instance. For many, his hyper-visibility masked the similarities between their respective aesthetics. Galliano’s 80s flamboyance, for instance, was tempered with an urge to rip fashion apart. “Judy Blame, Christopher Nemeth, John Flett, John Moore, all that posse. That’s what we were into,” he states. “A lot of the experimental was what one did as a young designer anyways in the 80s: the inside-out, the upside-down. We were all doing it in London anyway.” Galliano turned out tricks like deliberately-misbuttoned waistcoats puckering and twisting torsos, trousers worn as jackets, corks and coins as unconventional fastenings and white paint – a Margiela signature – liberally plastering hair and splattered over garments. And Margiela himself, long whitewashed as an edgy Belgian deconstructionist, obviously had a romantic side – his long slip dresses like linings ripped from grand ball gowns, his spring 1993 collection festooned with gold braid embroideries over billowing white voile dresses, his first jacket with those narrow puffed Victorian shoulders. There’s romance in the bones of Margiela.

“It’s wrong how people sometimes describe his work,” says John Galliano, today. “Everyone has to look at his earlier work to really get what Martin was about. It was full of emotion and it was romantic. That early stuff. Flea-bitten, put-together. Fierce. Fierce. And romantic.” Galliano inhales from a cigarette – today, smoking is his only vice, alongside the Tarte Tropézienne, a citrus-infused brioche filled with crème pâtissière made by Galliano’s cook, a white witch who wards off mosquito bites by pressing the sign of the cross into the skin with the end of a fingernail, Galliano tells me, an eyebrow raised. Add to that list of vices romance: Galliano is an incurable romantic, as that aforementioned near Grand-Guignol story testifies. Galliano also tells me that his aforementioned neighbour, the nonagenarian Princess Napoléon, dances through the forests of their adjoining properties dressed in white in the dead of night. The ravishing Miss Havisham imagery is pure Galliano fantasia – one part couture, one part Capote, it has the ring of truth. But not too loud a peal. That princess could have inspired one of Galliano’s previous collections, which came imbued with complex storylines, individual characters inspiring fabric treatments, creative approaches, drama sewn into every seam – and although his work has evolved and matured, that sensibility is constant. “It’s less literal. There’s not really a narrative anymore like there used to be. Other things that are different: influences and a younger energy,” Galliano reasons. “But I am a romantic. You can’t deny yourself. I wouldn’t be JG if I did.” He pauses. “Martin was too. When we had our famous tea together, it was then I discovered his love for 17th-century French literature and 18th-century costumes. He loved it. But he wouldn’t go there because you-know-who was cornering that market…” Again, that wicked laugh.

“I am a romantic. Martin was too. When we had our famous tea together, it was then I discovered his love for 17th-century French literature and 18th-century costumes. He loved it. But he wouldn’t go there because you-know-who was cornering that market” – John Galliano

Galliano and Margiela met during his early months at the house, before his first show: it was important for Galliano to feel that Margiela felt the house was in safe hands (he seemingly did). For a designer obsessed with anonymity, Martin Margiela is one of the most present presences on the international fashion scene. His clothes, his shows, his overall conceptual conceits are all often (and arguably all too often) referenced. Monsieur Margiela himself – now apparently teaching painting in Paris – has come out of his grand seclusion to co-curate two exhibitions of his work, one at the Palais Galliera devoted to Margiela, another of the clothes created during his tenure at the French luxury leather house Hermès between 1997 and 2003, shown at the ModeMuseum Provincie Antwerpen (this year transferred to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris). He still isn’t doing interviews, but in an unprecedented step seems to be taking ownership of the ideas the Maison originated and which have fallen into popular fashion vernacular.

Galliano himself was an ardent Margiela fan – and a client of the designer’s menswear. “I remember the best pieces I bought. The trench that was made out of old printed shopping bags. A fab knuckleduster that they tried to take away from me on the Eurostar. I know the pieces,” says Galliano, ticking them off on his fingers. “The jumper with the net tulle over it. I was a great fan. And loyal fan. When Martin was there, I bought and wore the stuff. Oh I have the white painted jeans, the white painted boots. I have the iconic pieces.”

Yet there is no urge for rehash – at least, no urge from Galliano, who at Margiela is ironically one of the few untouched by the surge in interest in the original creations of the label’s founder. Possibly the establishment re-emergence of Margiela – both man, and maison – in museums have influenced Galliano’s radical reimagining of what the label could mean in the 21st century. But it is also an oddly prescient approach he has taken from his first collection for the house – never relying on the past of Margiela to inspire the present, or the future. After all, the Margiela label is symbolically white; Galliano has taken it as a literal blank canvas. “We’re not there to curate Martin’s work. That’s why I keep saying let go of the corpse. Let go of the corpse. You can only do that for so long. And then you can put yourself into a corner and that’s all you’re doing. Let’s be brave and let’s possibly shine a light on a new way to go maybe,” states Galliano. “I didn’t want to go there to curate. That would be too much of a day job, for me. I made it very clear at the beginning, with the guys that be and the teams. At the beginning, of course, everyone went through the archives. How could you not? They’re amazing. We actually put them into shape, put what was missing back. There’s proper archives now. But it would just be too easy. Just curating. It’s like treading water. How long can you tread water for?”

That’s not to say Galliano has jettisoned Margiela’s influence entirely. It would be not only sacrilege, but near-impossible. Alongside very few other designers – Azzedine Alaïa, Rei Kawakubo, Miuccia Prada, Vivienne Westwood, Yohji Yamamoto and Galliano himself – Margiela’s work defined the lines of the last quarter of the 20th century, and laid the foundations for the 21st. You can see subtle echoes of Margiela’s working techniques, his lines and approaches to fabrics and cuts – a use of slick, plasticised surfaces, the sloped shoulders, a love of the dishevelled and unfinished as a form of unconventional decoration. A frayed hem, instead of a fringe.

“I am a romantic. Martin was too. When we had our famous tea together, it was then I discovered his love for 17th-century French literature and 18th-century costumes. He loved it. But he wouldn’t go there because you-know-who was cornering that market” – John Galliano

Yet Galliano’s iterations are utterly idiosyncratic – not Margiela, nor entirely Galliano (at least, how we used to know him). “I’d like to take it, be inspired by it and make it go somewhere. Or just the idea of exploring the idea of a new glamour – that was part three you just saw [at the haute couture]. I feel like I’m working like Martin. I can really put my hand on the heart and say that. I didn’t find that in the archives – but just the thinking of it. The nomadic idea – it’s territory that he explored... Upside-down stuff. Arriving at it through a psychology is much more interesting, fresh, and inspiring for me and the team. Because otherwise we are just curating. How creative can you get when you just curate? You need the surprises. You need the failures. You need the things that work, that don’t work. There has to be the element of surprise.”

There are few more surprising stories than the spectacular fall and rise of John Galliano, his rebirth at Maison Margiela, the rediscovery of a talent championed as one of our era’s finest. More surprising still, today fashion’s arch romanticist is making clothes inspired not by historical nostalgia, but the digitised landscape of contemporary culture, with its challenges to traditional, established notions – of luxury, of gender identity, of the reasons for dressing. “It is an inspiring time. It really is I think for a designer. For sure,” says Galliano. “I don’t just want to connect with the world. I need to connect. I need to be stimulated. I need to get excited. I need to give that energy to my team. I need to feel like it’s new, to get me out of bed.”

HAIR Akki at Art Partner MAKE UP Kanako Takase at Streeters using Laura Mercier MANICURE Maki Sakamoto at The Wall Group using ESSIE CASTING Anita Bitton at establishmentny MODELS Massima Desire at Next, Alanie Quinones at The Society PHOTOGRAPHIC ASSISTANTS Henry Lopez, Darren Hall DIGITAL TECHNICIAN Nick Rapaz STYLING ASSISTANTS Jordan Duddy, Tess Pisani, Alex Assil MAKE UP ASSISTANT Megumi Onishi