Invisible Men, held at Westminster University’s Ambika P3 space, features 167 pieces, spanning Alexander McQueen, Comme des Garçons and Craig Green

- TextJack Moss

In 1971, the famed British portrait photographer Cecil Beaton held an exhibition at London’s V&A Museum. Titled Cecil Beaton: A Fashion Anthology, it collected a series of haute couture gowns from the women of the beau monde – selected by Beaton himself – which were later added to the museum’s permanent collection. “The museum shares Mr Beaton’s belief that style in dress is an art form, worthy to be collected and displayed,” Sir John Pope-Hennessy, the then-director of the V&A, said at the time. Beaton’s assertion – that fashion could, indeed, be worthy of a museum’s hallowed halls – heralded the birth of the fashion exhibition as we now know it and, five decades on, serves as the inspiration behind this month’s Invisible Men, a new anthology exhibition of menswear held at Westminster University’s Ambika P3 space.

Marking the largest exhibition of menswear ever to be shown in the UK – its various garments drawn from the expansive Westminster Menswear Archive – Invisible Men hopes to prove men’s clothing is just as important to the pantheon of fashion as its female counterpart. “I’m hoping that this exhibition is a turning point and that other institutions and museums start showing menswear as integral to their fashion collections and exhibitions,” says Professor Andrew Groves, who co-curated the exhibition and has been developing the archive, used primarily as a teaching tool for design students at the university, for the past three years (Groves is course director for BA Fashion Design at Westminster). Just as Beaton successfully opened the doors to fashion at the V&A – in the decades since, fashion exhibitions like Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty and Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams have been the most popular in the museum’s history – Groves hopes to do the same for menswear, which remains underrepresented in institutions’ fashion collections and exhibits the world over.

“We are constantly told that fashion equals womenswear,” Groves tells Another Man. “The structures around fashion [are] constantly reinforcing the notion that ‘fashion’ doesn’t include menswear, and therefore, by implication that menswear cannot be as interesting or exciting.” Invisible Men, which over its 167 garments spans historical military garments and uniforms to contemporary pieces by designers like Alexander McQueen, Comme des Garçons and Craig Green, seeks to redress the balance. The name, Groves says, is twofold. “Firstly, it refers to the lack of exhibitions that are either devoted to menswear or that could have contained menswear but didn’t. Both Savage Beauty and Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams could have included menswear yet didn’t – the men became invisible,” he says. “Secondly, it is a reference to a design strategy that is prominent within menswear that obsesses over details that remain largely unnoticed except for those in the know.”

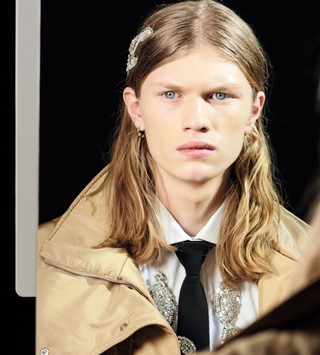

As such, much of the exhibition places focus on functional, utilitarian garments – among them industrial, military and workers uniforms, from postmen to railway engineers, and sportswear – and the way these have been reinterpreted or reworked by contemporary designers and labels. “Menswear is the story of functionality, even if that functionality has become obsolete, redundant, or its uses long forgotten,” Groves says. “The roots of many of today’s iconic menswear garments date back to their military ancestors from almost 100 years ago, the trenchcoat, the duffle coat, the parka. There is something poetic and at the same time incredibly melancholic seeing men dressed for long-forgotten jobs or trades.”

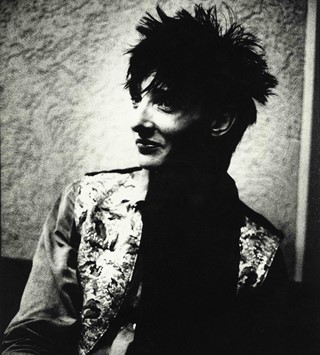

Among the 50 designers on show, a special focus has been given to Alexander McQueen’s menswear, an element of the late designer’s work all but written out of his legacy. “As someone that worked with McQueen in the early days, I knew how much the menswear was part of his design sensibility,” says Groves. “Some shows, for example The Hunger from S/S96, starts with menswear, closes with menswear and a third of the show is menswear. It was central to his design approach, rather like Helmut Lang’s was at the time.”

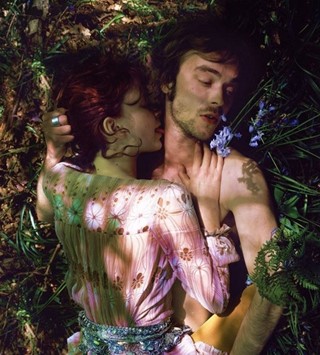

The McQueen garments will likely provide the exhibition’s biggest draw, many of which have not been on public display before. “I think behind that gothic presentation; people have an emotional engagement because of his ability to show beauty in a way that was flawed, raw and that had both a strength and fragility at the same time,” Groves says of why he thinks people remain fascinated by McQueen’s oeuvre. “If you look at the menswear from those early days, now 20 years on, it seems so refrained, pure, and calm.” Highlights include a halter-neck priest vestment from his A/W98 Joan show (“it is clear that McQueen was reflecting on the orthodoxy of gender norms and subverting them through the use of tailoring,” says Groves) and a spliced Glen plaid suit from his notorious 1998 ‘Golden Shower’ (officially Untitled) collection.

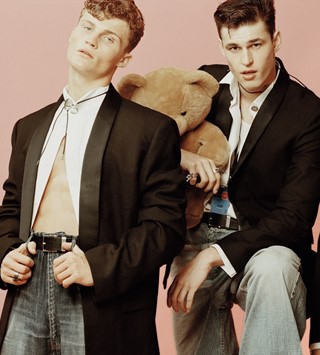

Invisible Men, and the Westminster Menswear Archive – which now contains over 1,700 pieces – have become something labour of love for Groves, who found the majority of the garments through avid internet research. “I had 99 email alerts every day for eBay, and every morning I would go through all those emails to see if there was anything worth buying,” he says. “Many things that we have had alerts for never turned up anything, so there are gaps in the collection. But it’s a very new archive, and we are working to fill those gaps.” Much of it comes down to instinct – as was the case for a hi-vis railway worker’s jacket, shown as part of Christopher Bailey’s final collection for Burberry, which is on display as part of Invisible Men. “As soon as I saw it come out on the runway, I knew we had to have it for the archive – I actually went up to the model afterwards and was trying to get him to take it off so I could get a closer look at it,” he says.

Ultimately, he does so for the students – whether from Westminster or from institutions further afield – who visit the archive each year. “People wrongly believe that everything is online or that we can understand a 3D object via a 2D image,” he says. “But I wanted to ensure that designers were engaging with physical objects and material culture, to enable them to understand the touch of the material, the fit of the garments, to see inside... to appreciate those hidden details.”

Invisible Men is open at Ambika P3, University of Westminster until November 24, 2019.