We remember the Joy Division frontman’s style, which rejected the artifice of rock and roll for the realities of everyday life

- TextJack Moss

Joy Division’s first album, Unknown Pleasures, was released at the tail end of the 70s, in 1978. Its cover alone suggested a departure from the blown-out artifice of the decade, of glam rock, or disco, or punk: designed by Peter Saville, it is simply a white-on-black illustration of the pulsar waves given out by a collapsed star. There is no title on it, nor band name. “It was the post-punk movement, and we were against overblown stardom,” Saville would later say. “The band didn’t want to be pop stars.”

The mythic appeal of Joy Division largely circles around Ian Curtis, the band’s frontman, who would go on to take his life at the age of 23, just prior to the release of the band’s second album, Closer. “Ian was the instigator,” said band member Peter Hook – it was he who would pick out a song’s melody, or arrive in the studio carrying shards of lyrics in a plastic bag. The songs he wrote were entwined with the way he saw the world: stark and unflinching, they revealed a sort of omniscient existential dread. “In his songs, ordinary life achieves an epic grandeur,” wrote Simon Reynolds in The New York Times. “But there’s no bombast or emotional theatrics; instead there’s a modernist starkness as pared down as a Samuel Beckett play.”

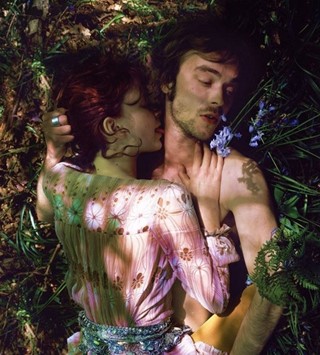

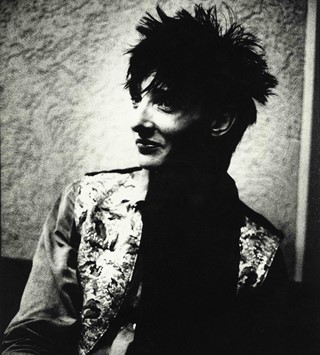

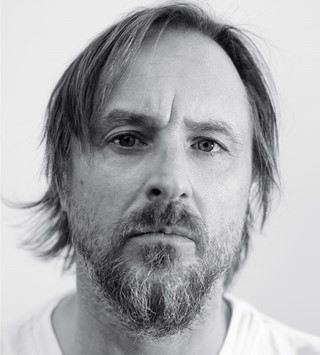

If it seems reductive to talk about what Curtis wore, it shouldn’t be: clothing would become integral to Joy Division’s music, a symbolic break from the showmanship of the musicians who ruled the 70s, and had first inspired them (Curtis long-cited David Bowie as formative, and the band first came together after a Sex Pistols gig). Reynolds deems it a “bleak glamour” – crumpled shirts, tailored trousers, leather shoes and Curtis’ signature grey trench, which he wore with the collar up, as if to protect himself from the world. There are a relative few photographs which exist of him; in the ones that do, he peers gloomily outwards, cigarette in mouth, the remains of industrial Manchester looming behind him.

Curtis was born and grew up in Macclesfield, just outside of the city, and the oftentimes desolate landscape of working-class life there seeped into his music – “Joy Division sounded like Manchester: cold, sparse and, at times, bleak,” said Bernard Sumner, another of the band’s founding members, in his autobiography. Growing up, Curtis was bookish, and shy. He followed the rules. By the end of his time at school he was a prefect, though he left before he completed his A-levels. Afterwards, he worked in a record shop; then, at the Macclesfield unemployment service. There is a photograph of him at the latter’s Christmas party, recently rediscovered. He wears a sweatshirt, a collared shirt pointing out, and jeans. He could be anyone.

As the years passed, he continued to live a normal life: when Joy Division was formed, Curtis was already married and had a child, living in a terraced house in the town where he grew up. And it was this life – the everyday life – which he would go on to write songs about, not the minutiae of it, but the strange, inpenetrable mysteries of being alive. “Existence, well what does it matter?” he sings on Heart and Soul. “I exist on the best terms I can / The past is now part of my future / The present is well out of hand.” His claustrophobic lyrics are now prophetic. In 1980, as Joy Division embarked on their first US tour, he took his own life in the front room of his Macclesfield home. He would not live to see the release of what would become Joy Division’s most famous song, Love Will Tear Us Apart, which came out two weeks later.

There is a video of Joy Division performing She’s Lost Control on BBC’s Something Else in 1978, eight months before Curtis died. It begins cropped into his face, which is sweaty, and dotted with acne. He stares vacantly outwards. He wears a dress shirt, trousers, polished shoes; the clothing of a man you might have passed on the street. But this apparent normality is simply a guise: as the first chorus ends, and Sumner’s guitar kicks in, Curtis’ eyes roll backwards into his head, and he jerks alive; his body contorts and twists, arms flailing, as if posessed. Beneath the measured exterior – beneath that stark, utilitarian uniform – was something else, intoxicating and violent, waiting to escape.