How Craig Green Became a Mainstay of London Menswear

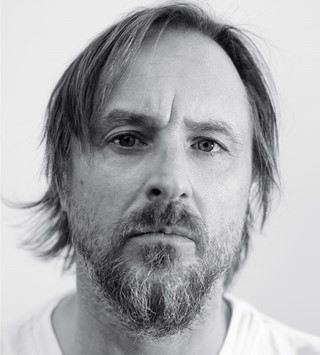

One of fashion’s most vital, fascinating and romantic voices: Charlie Robin Jones shines a light on the Craig Green phenomenon

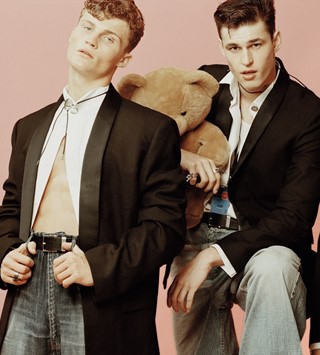

In late December last year, I catch Craig Green hard at work on his new collection. Anticipation is high after a big 2017. Funnily enough he’s preparing a collection about the codes of smartness itself. “The starting point is always some kind of reference to uniform or workwear,” he tells me on the phone from his studio between fittings and appointments. “So this time it was looking at gig lines [the military term for the vertical alignment of trouser fly, belt buckle and shirt placket], the idea of pressing folds into garments and creating ridges that make you appear ready for work.”

Mid-way through last year, he hinted that this collection would be more focussed on the present than previous collections. In fact, he says his mind is on the future – or at least an old vision of it: “[Those conversations around folds] developed into looking at ideas of trapping garments in other garments: forming, moulding and casting clothing. First we looked at [new techniques of] forming and bonding clothing, but instead of looking very modern, it seemed very un-futuristic and a bit old-fashioned,” Green says. “Around the studio, we had a book about making paper costumes from the 70s. It has this one section called ‘The Future’, which had costumes made out of tin foil, with plastic drinking cups all over them, which signalled this naivety and positivity about the future. So we took it back to very basic garments and very basic techniques of creating volume, which in the end felt more futuristic, but also had a naivety about this idea of the future.”

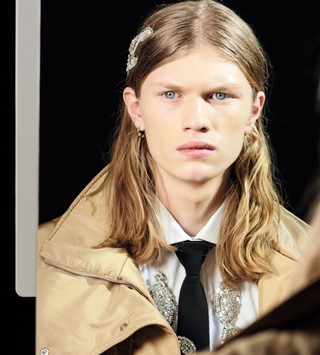

In early 2013, Craig Green emerged into an industry – and a city – that was straining to adapt to monumental political, economic and technological shifts. Fashion as an industry was learning, sometimes painfully, about the new realities of social media and the politics of inclusion, at the same time as austerity and sluggish, post-Great Crash growth were decimating London’s creative industries. Yet the course of ten seasons, he’s triumphed, making front-page ready statement sculptures out of scribbles and reducing a front-row to tears. Along the way, he’s received a clutch of the most important prizes in fashion, including Dress of The Year for a menswear look made out of scaffolding tarpaulin and British Menswear Designer of the Year 2016 and 2017. More importantly, he’s made ten sets of jaw-droppingly beautiful clothes that intimately speak to Big Subjects of our age: labour, the fluid yet tribal nature of cultural identity, even masculinity itself. And while he hasn’t yet overthrown late capitalism, his work ethic, poetic radicalism and DIY communitarian ethos has cemented him as one of fashion’s most vital, fascinating and romantic voices.

“I like to keep things as a family, and to have freedom to do what we want to do, and make the decisions we want to make” – Craig Green

Last year presented something of a coming of age for him, designing clothes for the Alien franchise, executing a Skepta-endorsed Moncler collaboration, pulling off two incredible collections and winning the BFC/GQ Designer Menswear Fund, which came with a business-transforming capital injection of £150,000. “When we were applying for the GQ award we wrote business plans for the first time. The money was very well used, and led to positive developments: the company was three people and now is nine people,” he explains when I ask about future plans. “I like to know what’s going on, problem solve, and try to build things bigger. [But] it’s an industry that you can’t really have a [strict] plan – it changes so quickly and easily. We’re fully independent at the moment and my aim is to try to keep it independent for as long as I possibly can. Never say never, but I like to keep things as a family, and to have freedom to do what we want to do, and make the decisions we want to make.”

In retrospect, it was always obvious that he was going to go far, designing, as he does, well-made, subtle, strange and deeply intelligent clothes his customers wouldn’t feel weird going to the pub in. “Approachable” isn’t a dirty word for him, and neither is “beautiful.” Yet he’s quick to underline the importance of creative mistakes, mentioning that far from a laser-focus on fashion from childhood, he originally went to college wanting to become a painter or sculptor, before pursuing fashion print, then an MA under Louise Wilson at Central Saint Martins. He wonders if this license to simply try stuff out still exists in the world of ballooning student debt and the cost-of-living crisis: “It was all very haphazard, I guess you could call it. We had that freedom to make mistakes, find out and developing our own way, which I think is a sad thing that will be lost with all the tuition fees increasing. Now at university you have to have a set plan because you’ll come out with such extreme debt that there isn’t the space to make mistakes. I think the mistakes are positive: it’s difficult but also freeing to not know the right way to do things.”

“Although there’s a certain mystery in what he does, there is always a great deal of emotion. You can tell that this comes from somewhere deep rooted, and true” – Vincent Levy

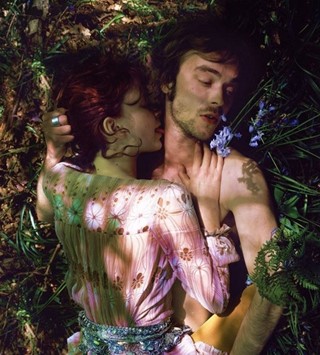

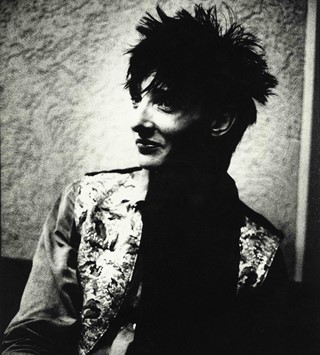

Each collection is a holistic idea, with inspirations ranging from the fear of the sea to the notion of paradise and devotion, and incorporating fabrics from devotional prints to industrial coverings to Madchester tie-dye. Yet his central practice has remained remarkably consistent: he examines the uniforms men wear when they go to fight, pray, dance or work, isolating and extending details, to form his own deeply personal design language. Frequent collaborator Vincent Levy says that this is something that stretches back before his first collection: “I think his garments have always told the same story in some way, and each piece, or each collection, is just a new way of fleshing out that story a little more. I remember the first designs he made when we were on our foundation course at Central Saint Martins, which were actually womenswear, and lots of the design codes you see now were already in place. His aesthetic has always seemed to come naturally, as something that’s more innate than referenced.”

There’s other repeated themes too: a worker’s jacket that has appeared in every season, staggering (and, Green jokes, often violent) campaign images, and the use of sculptural elements in the show presentation, which have included pieces of monochrome wood and free-floating framed fabric all made with David Curtis-Ring. On the occasion we speak, Green has just returned from meetings about the next season’s: “We think of them as emblems almost, or objects that we’re playing with. Sometimes they don’t work and the show doesn’t have any sculptural element, but I like them. They help to twist the reality even more: the person wearing them becomes an environment almost. They come from somewhere innocent: I like the idea that the sculpture is a separate entity, in some way, to the clothing.”

Green often uses the word “we” where other designers might use “I” and is famous for a tight circle of collaborators, many of whom he’s worked with since the beginning. Levy describes his working process: “He’s always really fun and open, but also knows exactly what he wants, which is rare and reassuring. He lives and breathes what he does, and you just do your best to be along for the ride in the moments he needs you. Everyone around him is going full pelt for the same cause, and in the times you’re in that environment you just have to grab an oar, and do your best. Although there’s a certain mystery in what he does, there is always a great deal of emotion. You can tell that this comes from somewhere deep rooted, and true.”

Charlie Robin Jones is a Berlin-based writer and consultant who has worked as head of digital at 032c, commissioning editor on the Guardian’s World Networks and editor of Dazed Digital.