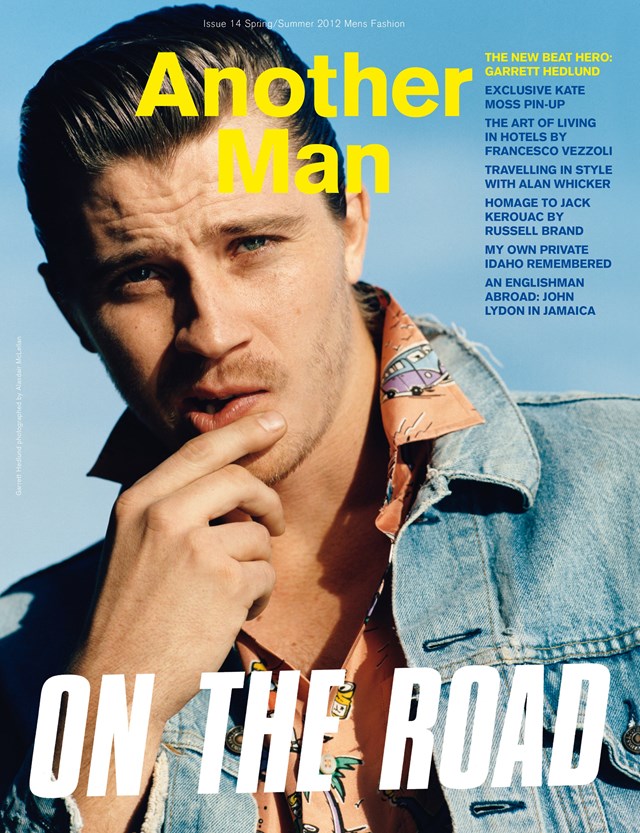

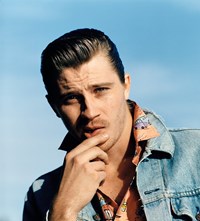

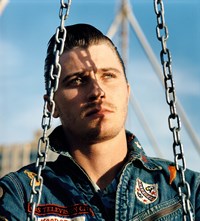

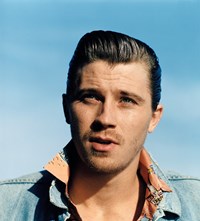

Garrett Hedlund

Garrett Hedlund first read On The Road in 2002, when he was just 17 and still attending high school in Scottsdale, Arizona. “I was a kid living with my mother, land-locked in the middle of nowhere, wondering how the fuck I would ever get a shot at life,” he remembers, “Kerouac’s beautiful poetry kicks in early on in the book and it just hooked me. It was like, ‘Yes! This is how it should be.’”

Hedlund suddenly recites one of the best-known passages in Kerouac’s novel, sounding like the ghost of the man himself: “...the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say commonplace things, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars...”

He pauses for breath, then says without irony, “If you’re young and a little bit lost like I was back then, but you have freedom running through your veins and a yearning to run and scream and laugh, those words speak to you of endless possibility.”

Ten years on from that epiphany, the 27-year-old Hedlund, thus far best known for his starring roles in the Tron reboot and Country Strong, is about to co-star as Dean Moriarty, a thinly disguised version of Kerouac’s real life friend Neal Cassady, in Walter Salles’s much-anticipated film adaptation of Kerouac’s generation-defining novel On The Road, first published in 1957. The film also stars Sam Riley (Sal Paradise aka Kerouac) as well as Kirsten Dunst, Kristen Stewart, Steve Buscemi and, intriguingly, Viggo Mortensen as a young William Burroughs.

It has been a long time coming, the rights to the novel having first been bought in 1979 by Francis Ford Coppola, who somehow never finally got round to making it. Since then, the novel has fallen from fashion, its often wide-eyed depiction of the nomadic bohemian life no longer as talismanic as it once was to the generations that immediately followed in the footsteps of the Beat generation, a loosely-connected bunch of writers that defined an alternative way of living in the shadow of World War II. They included Burroughs, an experimental novelist who wrote about his drug addiction, and the poet Allen Ginsberg, who was openly gay at a time when it was dangerous to be so cavalier about one’s sexuality. Both were subjected to obscenity trials for their first books: Ginsberg’s Howl, published in 1956, and Burroughs’s The Naked Lunch, which came out in 1959.

It was Kerouac’s On The Road, though, that most defined the Beat generation: its ideals and its values; its nonchalant attitude towards drugs and sexuality. In doing so, the book helped create the template for the wild social experimentation of the late 60s – the drug taking, the sexual freedom, the spiritual questing – and, it could be argued, for the more libertarian world we live in today. “Challenging the complacency and prosperity of postwar America hadn’t been Kerouac’s intent when he wrote his novel,” his first biographer and confidante, Ann Charters, later wrote, “but he had created a book that heralded a change of consciousness in the country.”

On The Road was actually written in 1951 when, legend has it, fuelled by amphetamines and coffee, Kerouac typed the words over three weeks on to a now famous long scroll of teletype paper. The novel recounts his travels across America in the late 40s, as well as the exploits of his friends and fellow hipsters, most notably Dean Moriarty aka Neal Cassady. In the six years it took for On The Road to be published, American society underwent a seismic cultural shift with the emergence of a new breed of rebellious stars like Elvis Presley, James Dean and Marlon Brando. In art, Jackson Pollock made action paintings that exuded a similar sense of “nowness” suggested by the famous Beat dictum that “first thought is best thought”. Burroughs later reflected: “The Beat literary movement came at exactly the right time and said something that millions of people all over the world were waiting to hear... The alienation, the restlessness, the dissatisfaction were already there waiting when Kerouac pointed out the road.”

Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, on March 12, 1922, Kerouac’s prowess on the football field earned him a scholarship to Columbia University, where he began writing for the student magazine. He dropped out when his fledgling football career stalled, and, for a short time, served as a Marine in the US Navy, before falling in with a bohemian New York crowd that included Burroughs and Ginsberg. Kerouac wrote his first novel, a traditional generational family saga, The Town and the City, in 1949. It was published the following year to lukewarm reviews.

He then spent the next six years writing and obsessively rewriting On The Road, which was originally titled “The Beat Generation”, a term both Kerouac and Burroughs came to hate. Initially, the term “beat” had a dual meaning for Kerouac: “beat” as in worn down by “straight” society and “beat” as in “beatific” – blessed, holy, transcendent. And nobody epitomised the spirit of Beat like Kerouac’s friend, Neal Cassady, the template for Dean Moriarty in the novel. While Kerouac came from a stable family background, Cassady had been raised by an alcoholic father and spent time in reform schools during his teenage years for stealing cars. For both Kerouac and the infatuated Ginsberg, Cassady was the real deal, an authentic free spirit.

“Neal was an energetic, instinctively brilliant and self-educated guy with a photographic memory,” Neal’s widow, Carolyn Cassady, who is 88 and now lives in Berkshire, told me a few years ago. “But, because of his background, a lot of the more academic Beats didn’t like him, didn’t trust him. Both Jack and Allen were blown away by him, though: his restless energy, his love of life, the way he talked, the way he lived purely for the moment.”

Garrett Hedlund also sees the true spirit of the Beat movement in Cassady. “Neal was it – the real thing. He grew up the hard way: there was the wino father who was never around, the stealing, the spells in juvenile hall, the young marriage to his beloved Mary Lou. That’s quite an apprenticeship, but he was so free-spirited, so unbowed by life, so up for it all. And that’s the Beat spirit, right there. Plus, he knew America. He knew the people. You get that from his writings, which are beautiful and full of memory and observation. It’s just that he never had the patience to actually sit down and write like Kerouac did... He was too busy living, I guess.”

Buoyed on a tidal wave of generational controversy, On The Road immediately became a bestseller and a zeitgeist book that, as Burroughs later put it, “sold a trillion Levi’s, a million espresso coffee machines, and also sent countless kids on the road”. It also influenced a host of other writers, musicians and artists, including Bob Dylan, who later said: “It changed my life like it changed everyone else’s.” For Tom Waits, the Beats were “father figures” who influenced his style and persona. For photographers such as Robert Frank and Stephen Shore, Kerouac was like a spirit guide as they crossed America taking new kinds of pictures that flew in the face of the Romantic landscape tradition of their precursors. (Kerouac even wrote the rhapsodic introduction to Frank’s seminal book, The Americans.) Kerouac’s restless spirit underpins the great road movies, from Easy Rider to Paris, Texas, and is there, too, in the frenzied catalogue of excess that is Hunter S Thompson’s gonzo masterpiece, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

For Kerouac, though, the book was a blessing and a curse. In Minor Characters, her memoir of life among the Beat writers, Joyce Johnson, who was briefly Kerouac’s lover, describes how they had stayed awake to buy an early edition of The New York Times of September 5, 1957 in order to read a glowing review of On The Road. She recalls Kerouac sitting in a coffee bar shaking his head “as if he couldn’t figure out why he wasn’t happier than he was”. They returned to her Manhattan apartment where, she writes: “Jack lay down obscure for the last time in his life. The ringing phone woke him next morning and he was famous.”

As was the Beat generation, which was derided on mainstream TV and across conservative America. Hurt by the constant criticisms of his book, and temperamentally unsuited to the fame it brought him, Kerouac retreated into himself. In a more recent biography, Paul Mathur wrote: “The obscurity that Kerouac by turn loved and loathed had vanished. He began drinking.”

Kerouac wrote several other books, including Vision of Cody, Big Sur (the next one lined up for the big screen treatment), The Subterraneans and the recently discovered The Sea is My Brother, written in 1942 and published last year, but none had the cultural impact of On The Road, which came to define him in a way he could not escape. Kerouac died from cirrhosis of the liver in 1969 in St Petersburg, Florida, the great adventurer having spent the last years of his life living at home with his beloved mother. He was by turns angry and bemused by the burgeoning hippie counterculture that his prescient book had undoubtedly helped bring about.

Neal Cassady died the year before. He had kept on moving, becoming court jester for the Merry Pranksters, a bunch of LSD-fuelled adventurers formed by the writer Ken Kesey in 1967. Cassady returned to the road, driving the Prankster’s dayglo-painted bus across America, the word “Further” painted on its destination board. His body was found by a railway track in Mexico, where he had perished from an excess of alcohol and barbiturates following a party.

“He went down there to calm down.” says Hedlund, who researched Cassady’s life before the cameras started rolling on Salles’s film of On The Road. “He wanted to provide for Carolyn and their children. That was a big thing for him, to try and be the father he never had. I sat with Carolyn for hours talking about him. The thing I came away with was that neither he nor Jack really knew how much each loved the other. Jack knew how much he loved Neal, but thought Neal did not reciprocate and vice versa. There’s a sadness in the relationship, the sadness of what was left unspoken. And you can feel that in On The Road.”

Indeed, for all its emotional gush and often overblown romanticism, On The Road is a book touched by sadness; an elegy for Kerouac and Cassady’s great journeys into consciousness, and for their youthful friendship. What, though, does it mean today in a time when the gap year has replaced the road trip as a youthful rite of passage? Does it stand up as a work of great art? (A haughtily dismissive Truman Capote once remarked of On The Road: “That’s not writing, that’s typing.”) Or is it simply a historical artefact from a time when things were more innocent and when the stakes were higher for those who challenged the orthodoxy of the mainstream?

Walter Salles, for his part, has said that he hopes his film of On The Road can have a deep resonance for today’s youth, noting that many of the themes of the book remain relevant, not least the question of how to define oneself in – and against – an increasingly conformist society. Whether his long-awaited big screen adaptation ends up succeeding or failing, Kerouac’s place in history is assured because whatever flaws he possessed as a writer he defined a moment, however fleeting, and in doing so helped create the shifts in the youth movement that followed, from hippie to punk to hipster. He would, though, have almost certainly been disgusted at the ongoing commodification of that culture.

“It’s all about money and surface now,” Carolyn Cassady told me with a sadness in her voice. “No one is the slightest bit ashamed of being superficial. I often thank God that Jack and Neal did not live long enough to see what became of their vision.”

But Garrett Hedlund remains optimistic, still believing in the transformative power of On The Road. “Times change,” he says, “You hear stories about what people tried and what people got away with back then. To a degree, it was a different America, a place that was trying to reshape itself after the war, and these young men were trailblazers. But, for me, the greatness of the book, and hopefully of the film we’ve made, is that sense of wonderment that they held on to. Kerouac looked at the beautiful imperfection of things and raised it up. He remade America in his great book. And maybe people need to do that again.”