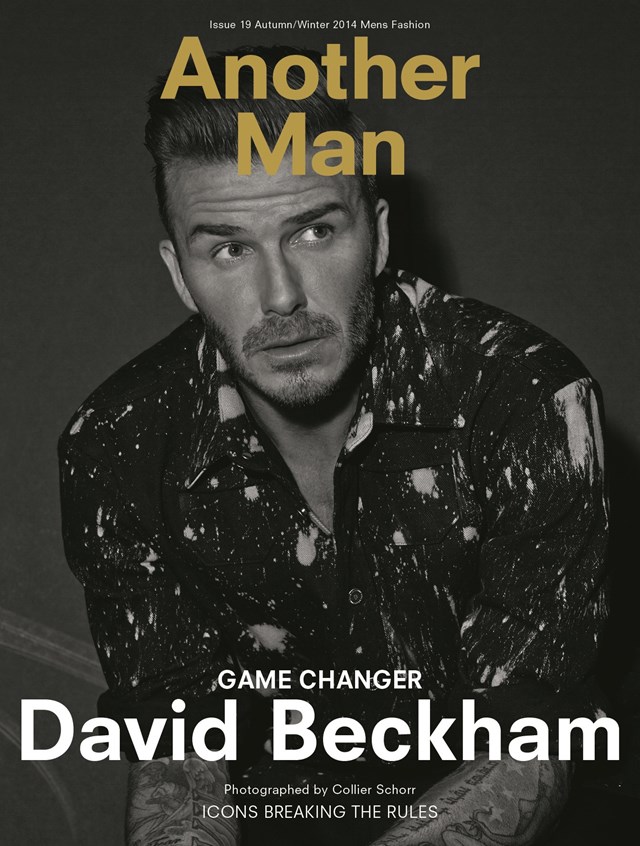

David Beckham

POP ICON. SPORTING HERO. FASHION PIN-UP. BRITISH AMBASSADOR AND FAMILY FIGURE… David Beckham MIGHT JUST BE THE ULTIMATE MALE ROLE MODEL. Tim Blanks GOES IN SEARCH OF THE MAN BEHIND THE MEGABRAND.

Once upon a time, religious icons gained their power from people. The more they were prayed to, the holier they became. Now, the new church is technology, sanctity has been replaced by celebrity, and the populace worships at the secular altar of fame. But the power of pop icons is still contingent on people. And – far above and beyond the halo effect of his ability to match foot to ball – David Beckham continues to have an extraordinary, mystical impact on people.

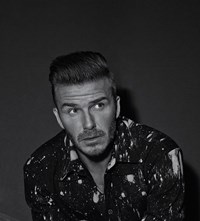

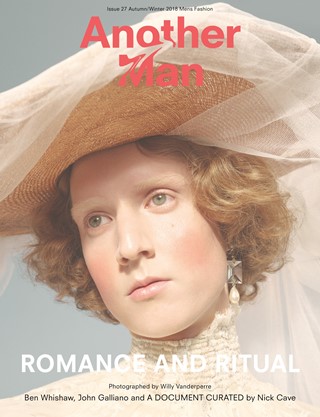

“He radiates openness,” says Collier Schorr, the latest in a long line of famous imagemakers to have fallen under his spell. “He is like a beacon drawing people close.” But while she was making her portraits of him, she was feeling challenged to explore what lies beneath, “to look for the introspection that surely exists in someone so at ease amongst people. There needs to be a dark side, even if it’s ultimately sweet.” Maybe that’s a natural reaction when you’re faced by something that seems too good to be true. For Pete’s sake, a sweet dark side?

But that might be exactly what Schorr’s pictures capture. Beckham himself recognised something different, if not dark at least raw, intense, introspective… and very male. “Collier twisted something out of me that was really good,” he said after he’d seen them. “I might have tattoos and things like that but getting a masculine shot out of me isn’t always easy.” True enough. We’ve all seen photos of Beckham that verge on camp in their parodic butchness. When she was informed about Beckham’s reaction to her portraits, Schorr wondered, “Did David see some shadow of himself in our pictures? An actor has that chance all the time, to see themselves attaching to a character not really their own. It may be a dark enough side to enjoy seeing oneself transformed.”

Is Beckham an actor, then? A consummate performer? Stylist Alister Mackie, who Beckham trusts to the point where he’ll agree to sport a little Raf Simons/Sterling Ruby tie-dye for a shoot, chimes in, “He knows how to be in front of the camera, just like an actor.” In fact, that degree of self-awareness was in full effect on Sky TV’s recent campaign for its new sports channel. Beckham moved through the ad with perfect timing, but absolutely wordlessly, which I took to be a sly acknowledgement of the one physical attribute he hasn’t been able to perfect: his voice.

But icons don’t need to – in fact, shouldn’t – speak. In that, Beckham is something like Kate Moss, another silent icon of our times. There are other clear similarities. They have both magnetised the lenses of the world’s top photographers, and the world seems to prefer both of them with the barest minimum of clothing. When I tell Beckham that no less an authority than La Moss recently said she has to pretend she’s someone else when she’s doing skin shots to stave off embarrassment or self-consciousness, he knows just what she’s talking about. “It’s totally nerve-wracking. Not wearing clothes is one way to be really self-conscious.” But he’s clearly got used to it since those early undie campaigns for Armani. It’s the barest necessity, after all, when everyone who shoots him wants his top off toot sweet.

“Obviously, you have to play a certain way in different shoots,” he continues, his keel as even as it remains throughout our conversation, “but I just try to be as natural as possible. For a start I’m not a model so I don’t try to be a model. I just try to be myself and hope that works.” And what exactly might that sense of self be? “Definitely not a model,” Beckham reiterates with a dry laugh. “I just try to enjoy these shoots as much as possible. You never know how long you’re going to get the chance to work with great photographers and great stylists and be on the cover of great magazines. I’m getting older now, I’m not sure too many people want to see me parading around in my underwear much longer. My body’s still OK but it’s only going to be a matter of time before people are like, ‘Really? Again?’ I’m 39 years old, I’ve got four kids, I’m not sure people are comfortable with that anymore.”

If I told him that the three most famous Brits of all time are allegedly William Shakespeare, Elizabeth II and David Beckham, how would he react? “I’d laugh,” he says, incredulous. “That part of my career and life still amazes me. Every time I visit these small villages in Africa or China or Brazil with UNICEF, there’s a young kid wearing a Beckham shirt or pair of shorts. In these villages, they’ve got one TV and all they watch is the Premiership, and it’s amazing the number of kids who know who I was or who I played for. It’s why I do the work with UNICEF, because obviously I am in a position to help people and make a difference.”

When David Beckham uses the word “amazing”, he has the rare knack of making you feel his amazement, so you can share it. He’s moved the family to an elegant residence in central London – with the politics of interior decoration fully analysed in the local media – at the same time as he’s keeping on the place in LA. “LA will always be our second home, so the kids have the best of both worlds.” But Beckham’s life is about to become a tale of three cities with the launch of his own Major League Soccer franchise in Miami.

“People tried to steer me away from Miami, told me it’s a tough city for a sports franchise,” he says, “but if I’m to start a team, I want to give it my identity. And Miami has always been a city I loved to visit.” There aren’t many players in sports who’ve gone on to be owners. Imagine if the planets aligned and Beckham ended up back at Man U as owner. “I’d probably put a shirt back on and try and play,” he says instantly. It makes you wonder what he thinks of the state of English football now: the brawls, the car crashes, the hairplugs… but he won’t be drawn.

“There’s always been certain times in a player’s career when he thinks, ‘I cannot believe I said that, or wore that, or flaunted my bank balance like that’. I can look back at things I said when I was 21 years old and I shouldn’t have done that, but when you’re young and you’re in the position I’ve been in over the years, you push boundaries and make mistakes. It’s part of growing up and finding yourself. I’m glad I’ve come to the end of my career as a hardworking footballer and a role model.”

“It must take a lot of energy to be so receptive to people,” says Collier Schorr, “but I think it’s why his popularity crossed outside football. It’s too simple to credit his handsomeness. Lots of people are handsome. It’s that he gives back all the affection bestowed upon him.” The icon that interacts – a uniquely contemporary paradigm. “I don’t think of that, to be honest,” is Beckham’s response to that particular chestnut. “I am who I am. I don’t think I’m better or different. I just treat people how I’d like people to treat me and my family. I’ve always been the same, I’ll never change.”

Last year’s documentary Class of 92 offered an entertaining glimpse of the crucible in which Beckham was formed. To see him with Paul Scholes, Nicky Butt, Ryan Giggs and the Neville brothers – “The Players Who Inspired a Generation” as the movie poster cheerfully hyperbolised – alongside the players from their youth club days raised the inevitable poignant questions about how and why extreme good fortune smiles on some people and not others… and how random that blessing is. “Obviously I’ve got a certain amount of talent to get where I’ve got,” says Beckham, “but I’ve played with and against a lot more talented players than myself and they’ve gone on to not achieve so much. There were a couple of kids I grew up with who were much more talented than I was, they just didn’t have the dedication or the right attitude. And some people were not lucky enough to have the support of their parents or someone to give them the drive to push further.”

In Beckham, that drive was such that he has never for a moment entertained the notion of what his life would have been like without football. He simply isn’t wired to think that way. “I know how unbelievably lucky I’ve been throughout my career, to have done what I’ve done, to be in the position I’m in now. So I never think about my career as being anything different to what it is.” His lack of questioning selfdoubt qualifies Beckham as a hero of the old school, gilded Siegfried rather than gloomy Hamlet. But that doesn’t mean he isn’t capable of detecting a grander design in the way things have turned out for him.

“Fate definitely played a big part in my career,” he says. “Being given the England armband was maybe down to fate. That was the best moment of my career without a doubt. Stepping out at Wembley wearing the England shirt, leading the team into the World Cup finals, that’s the biggest, proudest thing in my career.” Which begs a question so obvious it scarcely needs to be asked – what was the worst moment? “I’m not sure if people get tired of me saying this was the worst, but it was when I got a red card in the World Cup in 98. I went through a lot of heartbreak, so did my family.”

In that innocent era, before the internet troll oozed from under his digital bridge, anonymous viciousness still found a way to make its noxious presence felt. Beckham was hung in effigy: “It doesn’t get much worse than that,” he admits. He felt the pain again at the premiere of Class of 92, when he looked at his sons’ faces as the 98 World Cup came up, with the red card, that effigy… “They looked so sad, and they started asking me questions about it: ‘What did it mean?’ and ‘Why would someone do that to you?’ And that made me sad.”

Still, the classic hero must be tested, found human, but not found wanting. “The whole experience made me a stronger person. In the end, it made me a better person because I had to be. I was in the limelight not just for my football but obviously because I was married to Victoria. Maybe I wouldn’t have been able to handle both those situations. I look back and I don’t know how I did. I just did.” And, with the passage of time, Beckham’s even able to make a little light of the whole nightmare. “It wasn’t a very masculine thing to do, it was only a little flick as well,” he says ruefully. “But it happened.”

“The religious imagery and fairytales that formed our shared cultural references have been replaced by the cult of celebrity,” artist Alison Jackson wrote in 2009. Her work uses celebrity lookalikes to subversively re-order the lives of pop icons, the Beckhams included. “Celebrities have become visual shorthand for narratives that shape our lives,” Jackson continues. In David Beckham’s case, the narrative is The Perfect Parent.

All Beckham’s boys play in football Academies: Romeo and Cruz at Arsenal; Brooklyn at Fulham. “I want them to be involved in sport because it gives you that sense of being dedicated and focused and staying out of trouble. I think sport can do that for you.” Brooklyn is rumoured to be promising – would his father sign him? Beckham laughs. “Brooklyn has already said to me, ‘When the Miami team starts, can I go and play over there?’ I said, ‘Of course you can if you’re good enough.’ So he’s working his backside off to get in the team.” Another delightful prospect – is he ready for a teenage Harper unleashed on Miami’s South Beach? “I don’t even want to think about that. There are a lot of years before that happens. I’ve told her she’s going to be locked up in a tower like Rapunzel. I think she’s quite happy with the idea. She loves the film Tangled and I’ve told her it’ll be exactly the same as that.”

The kids are a constant in his conversation, as they’ve been a constant in his life. “They’ve lived my career with me. Every trophy I’ve won, I kept adding children.” He describes himself as loving but strict. “With kids, you just need to play a part in everything they do. That part of their growing up is part of who they grow into.” It makes the microscope the Beckhams live under quadruply difficult (there are, after all, four kids). He feels he always has to be on his guard. “I was at the baseball the other day and I was eating a hotdog, and I thought, ‘I bet someone just got a picture of me wrapped round this hotdog looking really unattractive’, and sure enough, next day there was a picture of me, mouth full of hotdog, looking very unattractive. But when I say I always have to be on guard, I’m actually really relaxed when I’m out because at the end of the day, 99 per cent of the time I’m with my children and I don’t want them to feel they have to be on guard all the time. It’s not a good way for them to grow up.”

And that highlights a curious fact about Beckham’s media profile. Sure, he gets blanket coverage for riding his bike down Sunset, or splashing around off Malibu. The ubiquity of the image is, after all, a condition of pop icon status. But the sting in that ubiquity’s tail, at least in the age of social media, is that the floodtide of photos will inevitably at some point present you at your absolute un-iconic worst. And then the public worm will turn with glee. Food and drink are the biggest pitfalls. Reflect, if you will, on the rich comedy of poor, doomed Ed Miliband trying to fit that bacon sarnie in his mouth.

So maybe it’s something as basic as the impossibility of Beckham ever taking a bad picture, even when he’s accessorised with a hotdog, that keeps his blanket coverage so strikingly benign. Or, more likely, it’s his Perfect Parent narrative, highlighting what a fab dad he is, or what a mensch he is with fans. Compare it to the endless jibes about Victoria’s facial expression or body size. It’s almost like Beckham’s become the salutary media reminder that, in a world full of assholes (assholes who were, in large part, created by those media in the first place), nice guys can finish first. And perhaps, when the modelling comes to an end, maybe even when football is finally behind him – and we’re clearly talking decades here – that will be Beckham’s lasting legacy. You can visualise the biopic already.

Beckham’s own screen favourites are films like The Notebook and Notting Hill. “I’ve always loved chick flicks,” he admits. “I get emotional at them.” Next, I suggest to him, he’ll be telling me Victoria loves horror movies. “No, but Brooklyn is slightly into them. He’s asked me to go with him to see these scary movies and I’ll say I can’t do that.” One thread of evolutionary science is currently attaching the future of Homo sapiens to altruism, survival of the nicest rather than survival of the fittest. If that works out, there’ll be holograms of David Beckham in every town square.

There is one last question, before reception fades as Beckham drives away into the San Bernardino Mountains to pick up his eldest from summer camp. Things I’ve been reading lately suggest that underwear is going the way of socks in the wardrobe of the contemporary male. Seeing I have an expert on the line, I have to ask, “Is going commando ever appropriate?”

“Being in the bodywear business, no, I don’t think it’s appropriate,” Beckham answers oh-so-seriously, with a smirk in his voice. “But I can see its advantages. I haven’t done it for a number of years because, as I said, I am in the bodywear business and I get free underwear, which is very good and very comfortable and very well-priced.”

See what he did there? Now he can continue on his journey, truly satisfied that the product has been successfully placed. And, for our part, when we see this week’s pap-snap of David Beckham riding his bike on Sunset, we can rest assured that he is, at the very least, fully supported.