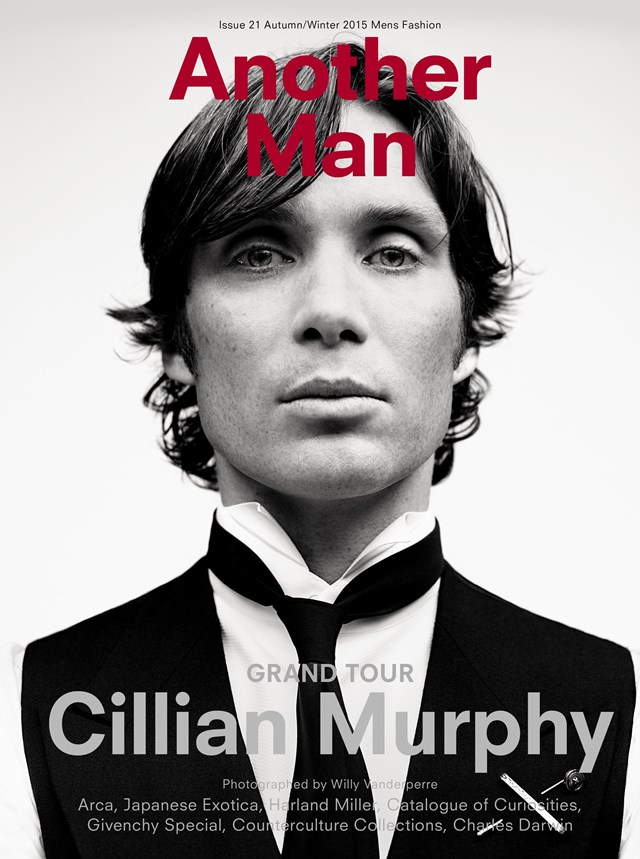

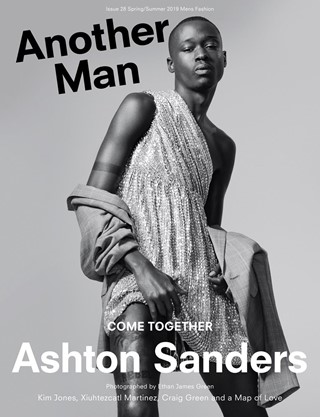

Cillian Murphy

Cillian Murphy SURVIVED THE LIVING DEAD IN 28 DAYS LATER, BATTLED BATMAN NOT ONCE BUT THREE TIMES AND, IN HIT TV SERIES PEAKY BLINDERS, WAGED GANG WARS ACROSS THE STREETS OF BIRMINGHAM. BUT THIS DECEMBER HE TAKES ON HIS GREATEST SCREEN ADVERSARY YET: AN 80-TONNE SPERM WHALE IN A RAGE. NOVELIST AND OBSESSIVE WHALE-WATCHER Philip Hoare TAKES THE BLUE-EYED STAR ON A JOURNEY DEEP INSIDE THE MYTHOLOGY OF MOBY-DICK…

“... Surely all this is not without meaning. And still deeper the meaning of that story of Narcissus, who because he could not grasp the tormenting, mild image he saw in the fountain, plunged into it and was drowned. But that same image we ourselves see in all rivers and oceans. It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life; and this is the key to it all” – HERMAN MELVILLE, MOBY-DICK

In his 1923 essay on Herman Melville, which helped recreate that long-lost author’s image for the 20th century, DH Lawrence wrote: ‘Melville has the strange, uncanny magic of sea-creatures, and some of their repulsiveness. He isn’t quite a land animal. There is something slithery about him. Something always half-seas-over. In his life they said he was mad – or crazy...‘

‘There is something curious about blue-eyed people,’ Lawrence concluded. ‘They are never quite human... About a real blue-eyed person there is usually something abstract, elemental... In blue eyes there is sun and rain and abstract, uncreate element, water, ice, air, space, but not humanity... Blue-eyed people tend to be too keen and abstract.’

I suppose I should have been warned. It is impossible to interview Cillian Murphy. His pale blue eyes refuse to allow it. OK, he is personable and kind and courteous, and arrives on time, and answers all my questions patiently, unerringly, and thoughtfully. But none of that means anything once you are held in his gaze. It is steady, and open, like his face. But his eyes dominate everything. One journalist even believed they should get reviews of their own.

We sit in Brighton’s best vegetarian restaurant, within sound of the sea. I’ve just been swimming, in the shadow of the skeletal remains of the West Pier, which stands like a blackened wreck on the beach, overflown by gulls by day, and by dark murmurations of starlings by twilight. This place, disparagingly called London-by-the-Sea, tenanted by a dilettante Prince Regent in his seaside extravaganza of a palace, is also riven with the darkness of the sea, with the gothic undertow of Brighton Rock and Patrick Hamilton’s black novels. The brutality of the sea undermines the town’s tawdriness, gives the lie to its veneer. It is a lonely place, for all its apparent celebration of life, for all the passion spent on its streets.

“Wow, it’s pretty blustery out there,” Cillian says, when I tell him what I’ve been doing. “I’m a pansy when it comes to swimming in the sea. It has to be really warm for me.”

It is difficult not to see the blue sea in those eyes. Indeed, he hails from Cork, on the west of Ireland, where its fragmented wilderness is held out to the Atlantic, a land more part of the ocean than it is European. It is the last of the land, or the fi rst of the sea. Little wonder then that Cillian spent his childhood on boats. Or that, as he has recently discovered, his own ancestors were shipwrights.

It is a given that Cillian Murphy is one of the most beautiful, as well as one of the most talented, male actors around. Directors such as Ken Loach, Neil Jordan, Christopher Nolan and Danny Boyle clearly agree. But he lacks any normal vanity one might associate with such a state of achievement. When we sit down, Cillian asks that he sit not facing the mirror behind me, since he does not want to look at himself. I leave that to the rest of the restaurant, whose diners, and staff, gradually become aware of his quiet presence.

He’s wearing dark clothes – a button-up, long-sleeved sweatshirt with discreet holes in the elbows. His skin is flushed with a faint tan. He has a fi ne, rusty-coloured 70s-looking moustache – he is in Brighton to play an Irish gangster in Free Fire, a new film from Ben Wheatley, director of A Field in England – and his hair is dark and streaky with silver, and long and locky, albeit soon to be shorn for the filming of the third series of Peaky Blinders.

“I don’t like it,” he says, screwing his nose up at the thought, “it makes me look like a Post Office raider.” Nevertheless, I assure him, it’s a very influential crop. With cheekbones like his, he would make the most desperate villain look like a Renaissance angel. He might be in a Visconti film as equally as in Reservoir Dogs. But today he looks like he could spend three years at sea, like the character he plays in Ron Howard’s new movie, for which he was physically transformed.

There’s something almost improbable about his presence – about any actor’s presence, really. It is a varnish bequeathed by mediation, replication and impersonation. He might be a CGI recreation of an actor, an unreality underlined by his boy-mannishness. Is he 14, or 40? It is almost impossible to tell. He might as well be an animation. In the video for his friend Paul Hartnoll’s recent track, The Clock, Cillian plays an automaton-like office worker marching through the Brutalist concrete of the Barbican – only to enter a fancy dress store where, like Mr Benn of the 1970s animated children’s series, he dons different guises – Manc clubber, leotard-wearing strong man, astronaut – acting out the multiple roles as cartoonish versions of himself.

In person, Cillian’s gentility evokes the childlike nature of great actors. He is both self-aware, and not. Even when he swears, which he does with elegance and grace, it is as if the innocence were being deliberately broken. It is this quality that has brought him to prominence. In Enda Walsh’s Disco Pigs, in which Cillian made his theatre debut back in Cork in 1996 (it was subsequently Cillian Murphy filmed in 2001), he played a blaspheming dysfunctional teen, albeit with an ethereal quality. In Neil Jordan’s 2005 film Breakfast on Pluto, he donned drag, but transcended the notion of playing transgendered to assume it as a state of mind.

Perhaps it is this apparent malleability which means that ‘Cillian Murphy’ works so well in Ron Howard’s new film, In the Heart of the Sea, a seafaring yarn with dark undertones. In it he plays Matthew Joy, the second mate of the whaleship the Essex, whose crew undergo extraordinary trials at sea. On screen, Cillian is both cartoon-like and deeply emotional: his face is almost impassive, and because of that impassiveness, extraordinarily expressive. That subtlety reads wonderfully on film; his performance ripples with it, like the ocean’s skin.

Like any good actor, Cillian is a blank slate on which we write our own emotions, on which we project our passions. Actors act out our fantasies, and their own; our nightmares, too. When I tell him I could never imagine going on stage, being so utterly alone and exposed out there (my exposure is the sea) he immediately leaps in, saying, “But it’s not me out there. I am someone else, someone I can hide behind.”

In the Heart of the Sea draws its power from the almost mythic story of the Essex, which set sail from Nantucket in New England in 1821, bound for the South Seas, in pursuit of sperm whales. The story is told by Owen Chase, the first mate of the ship (played in the film by the Australian actor Chris Hemsworth) and childhood friend of Matthew Joy, Cillian’s character. Chase was one of the few survivors, along with the captain, George Pollard – and his account of the dramatic events would later become the basis for Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick.

Those texts are founding fables, creation myths of modern America. Whaling was America’s first global industry. At that time, the oil from these animals lit and lubricated the Industrial Revolution. The civilised streets of New York, London, Berlin, Paris and St Petersburg glittered to their barbaric burning oil. Most prized of all was the fi ne spermaceti oil from the whale’s head, which earned it its name, since early hunters believed that this waxy substance, which spurted out when the head was pierced, was in fact the animal’s semen. (The sperm whale, I can attest, smells inordinately masculine; whalers claimed that they could smell it from miles away.)

Even now the bodily products of this deep-diving denizen of the dark ocean are highly valued: from one in a hundred whales comes the strange substance known as ambergris, known immemorially for its ability to hold fugitive scent and used by all the major perfume houses in their finest distillations.

To gather whale oil – which could turn the hunters into rich men – these 19th-century versions of modern oil tankers spent three or even five years at sea, filling their holds with barrels of oil from the whales they killed. It was a brutal job, and it is sensationally portrayed in the new film. In many ways, Cillian had to become a whaler himself.

“At first we were all going to the gym and practicing rowing,” he says of himself and his fellow cast members – although Chris Hemsworth, one must admit, hardly looks as if he needs it. “It was all a bit of waste,” he quips, “because we never take our tops off in the film.”

Initial filming took place in a studio outside London, on vast water tanks where the cast were blasted by water cannons and rocked on tilting rigs to emulate storms at sea. But this punishing sequence was about to get radically more physical. The true story of the Essex becomes dramatic when the ship is struck by a gigantic sperm whale in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, about as far from land as it is possible to be. Set adrift on lifeboats, the 20 shipwrecked men are reduced to starvation, and then resort to the time-honoured tradition – according to the laws of the sea – of eating one another.

When the last survivors – including Owen Chase and George Pollard – were rescued, they were still gnawing on human bones, and appeared reluctant to give them up. Pollard would later become a recluse back on Nantucket, secretly storing supplies in his attic, lest he should ever again face starvation. Chase was plagued by persistent and terrible headaches. Both men were probably suffering from what we would now diagnose as PTSD. By 1868, Chase was declared insane.

As the production of In the Heart of the Sea moved to location in La Gomera, one of the Canary Islands, the nature of the project became almost as extreme as the privations suffered by the crew of the Essex. “We were all men together,” says Cillian (as in Moby-Dick, there are virtually no female roles in In the Heart of the Sea). “We were all staying in one hotel, and things got a bit competitive. We had to lose weight for the later scenes in the film. We had a dietitian to coach us, but blokes being blokes, there was a race to see who could lose the most. We were meant to lessen our intake gradually, but some of them would fast for the whole day.”

Cillian lost a stone in a few weeks. It was a radical transformation. Since he normally weighs ten stone, that was a tenth of his body mass gone. (He still looks slight to me; when his dessert of ice cream arrives, he barely touches it.) The resulting scenes in the film are harrowing. It is difficult to believe that these men were not stranded, castaway sailors, at death’s door.

“For a few weeks you become an expert,” he says of the intense processes of acting in such a film. He had to learn how to tie ship’s knots, how to bark commands as a second mate. He’d read Moby-Dick when he was in his 20s, so he knew how Melville’s book related to the story of the Essex. Also required reading was Nathaniel Philbrick’s brilliant and best-selling book, published in 2000, on which the film is based, and from which it takes its title. When he read the script, Cillian was particularly drawn by the relationship between Matthew Joy and Owen Chase. “They’ve grown up together, sailing together as boys,” he says. “I could relate to that, because that was the kind of thing I did.” Unlike almost all the other actors, Cillian did not get seasick – for which he thanks, half-jokingly, his ancestral relationship with the sea.

Out of the cramped and stinking confi nes of the ship, the men would be lowered in flimsy whaleboats, double-prowed and built for speed, in pursuit of the sperm whale, the world’s largest predator. In Howard’s film, these scenes are excitingly, terrifyingly recreated. According to Chase’s account, the Essex was attacked by what appeared to be an enraged bull sperm whale – 85 feet long and weighing 80 tonnes. There has been much speculation as to why this animal – sperm whales are usually extraordinarily placid, even timid creatures, as I can attest – should have attacked the Essex. Was it seeking revenge for the whales that the ship’s crew had killed?

Certainly the whalers employed a cruel technique, killing the whales’ calves so that their mothers would come in close to protect them, and then get killed in turn. Was this real-life Moby Dick a Moby Doll, then, bent on avenging the attacks on her young? The only time I’ve ever experienced a whale getting angry was when I came a little too close to its young. The great thwack of its huge flukes, or tail, smacking down on the water, was a salutary reminder of the danger to those who used to hunt these Cillian Murphy animals. That descending, all-powerful tail was dubbed ‘the hand of God’ by the whalers, since it could dispense with their lives at a stroke, breaking their backs and speeding them into eternity.

Or was the ship, as some have suggested, a leaky vessel whose sides were easily stove in by the animal, in a ‘freak’ story used by its owners to claim the insurance money? In the Heart of the Sea places the real physical demands, and depredations that its men suffer against the unreal beauty of the whales, seen leaping and diving and swimming underwater, as if in another universe. When they meet, these two forces, it marks disaster for both. In the film – though not in Philbrick’s book – that story comes full circle with a final, poignant encounter between Leviathan and man.

“But how? Genius in the Sperm Whale? Has the Sperm Whale ever written a book, spoken a speech? No, his great genius is declared in his doing nothing particular to prove it. It is moreover declared in his pyramidical silence” – HERMAN MELVILLE, MOBY-DICK

Back in Brighton, far from such tempestuous scenes, the evening draws on, and we fall to talking about whales. Or at least, Cillian listens patiently to my tales of my obsession with the animals, which began when I was a child, but were rekindled by my first visit to Provincetown, Cape Cod, where I’d gone in the fateful summer of 2001, to hang out with John Waters.

John had reviewed my first book – a biography of the aristocrat, aesthete and bright young thing, the Honourable Stephen Tennant – in The New York Times, and we’d become friends as a result. “Come to Provincetown,” he said. I’d spent two weeks there, on the sandy spit of land that juts out into the Atlantic – once a whaling port, like its neighbour, the island of Nantucket. But it wasn’t till my last day that I realised it was also a place to see living whales. That afternoon I paid $12 and stood defiantly on the prow of a whale-watch boat. Half an hour later a 40-tonne, 40foot humpback breached right in front of me, hanging in mid-air like a barnacled angel suspended in space and time. I responded with an equally poetic “Fuck!” and my life was changed.

I became obsessed, as obsessed as I ever was with Stephen Tennant or Oscar Wilde or David Bowie. I returned again and again to Provincetown to commune with the whales. John accused me of being a whale stalker, said I was spending more time with whales than with human beings, and when I showed him my full frontal photographs of whales, he said, “That’s just whale porn.” John told me I had to write about my obsession to work it out – I think he was recommending it as therapy, out of pity for my psychiatric disturbance.

And so I wrote, and have spent 15 years chasing whales around the world. They still fascinate me, these creatures, which possess the biggest brains on earth, are the largest predators that ever lived, are the longest living mammals at up to 300 years old, yet who evince a culture of their own, expressed in their Morse Code-like clicks, and who swim in an infinite, alien universe, a balletic, three-dimensional existence in which we landbound humans are inept, pathetic bystanders to their intricate, interconnected choreography. Which is what brings me to this restaurant table in Brighton, talking to this Irishman.

"CILLIAN MURPHY TURNS TO THE SIDE OF HIS RESTAURANT BANQUETTE AND CURLS HIS LEGS AROUND, ELEGANTLY HOOKING HIS ANKLES TOGETHER. THE TOUGH SECOND MATE OF THE ESSEX WHALESHIP HAS TRANSFORMED HIMSELF INTO A POUTING COQUETTE, IN A TINY, SPLIT-SECOND PIECE OF THEATRE. AS HE HAS SAID, “AMBIGUITY IS THE THING THAT APPEALS TO ME”

From whales our conversation turns, somehow inevitably, to David Bowie. Cillian’s friend, the playwright Enda Walsh, is currently working with Bowie on the musical adaptation of The Man Who Fell to Earth, the 1976 film directed by Nicolas Roeg, in which Bowie transformed himself from the Thin White Duke into the flame-haired, cat-eyed alien, Thomas Jerome Newton. The production, Lazarus, will be staged in New York this autumn. Cillian tells me he’s read the script – he won’t divulge details, but says it is very good, of course.

Later, on the train home, I start to imagine Murphy in the part: like that other genre and gender-defying actor, Tilda Swinton, his own looks seem more than suitably androgynous, and alien. Then I cast him as Billy Budd, the ‘Handsome Sailor’ of Melville’s last, elegiac work, turned into Benjamin Britten’s equally forceful, pent-up opera in which young Billy, another fallen boy, the blue-eyed cynosure of the captain and crew, dies sacrificially for his innocence (Terence Stamp made his debut as Billy in the 1962 film version, with peroxide hair), and is consigned to the deep: ‘Just ease these darbies at the wrist / And roll me over fair! / I am sleepy, and the oozy weeds about me twist.’

We both become quite animated talking about Bowie. Cillian says that when he played the transgendered foundling Patrick Braden, in Breakfast on Pluto, he emulated Bowie’s way of sitting with his legs doubly entwined, as seen in the Omnibus documentary Cracked Actor – “like this”, says Cillian, as he turns to the side on his restaurant banquette and curls his legs around, elegantly hooking his ankles together. The tough second mate of the Essex has transformed himself into a pouting coquette, in a tiny, split-second piece of theatre. As Cillian has said elsewhere, “Ambiguity is the thing that appeals to me.”

Then the moment is gone. It is time to part. As we leave, the young people at the next table call Cillian aside to thank him for one of his performances. He smiles sweetly and thanks them, as if no one had ever said that to him before. It is dark outside now. The seaside streets have started to take on the anarchy and unknowingness of the night. I cycle up the hill to the station and Cillian returns to his hotel on the seafront, where, in the early hours that morning, the wind had raged and screamed at his window like a banshee, as if the waves had come back to reclaim their own.

“Now small fowls flew screaming over the yet yawning gulf; a sullen white surf beat against its steep sides; then all collapsed, and the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago.” – HERMAN MELVILLE, MOBY-DICK