Dean Mayo Davies talks to David Kramer, whose nostalgic art met its match at Celine’s S/S20 show at Paris Men’s Fashion Week

- TextDean Mayo Davies

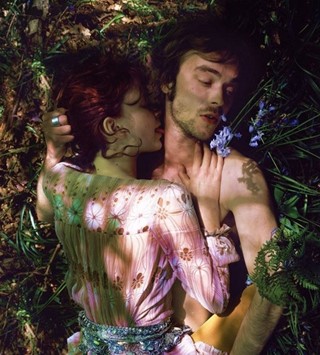

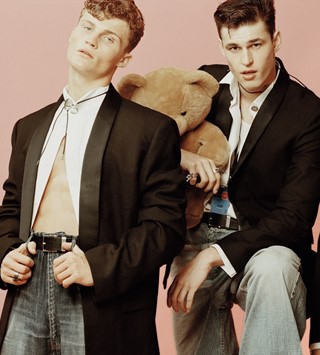

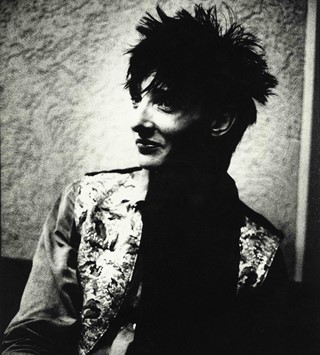

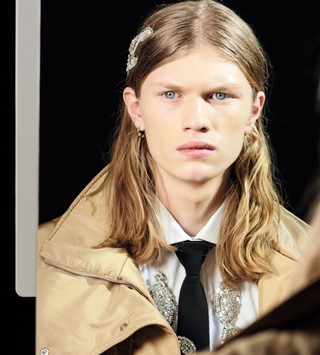

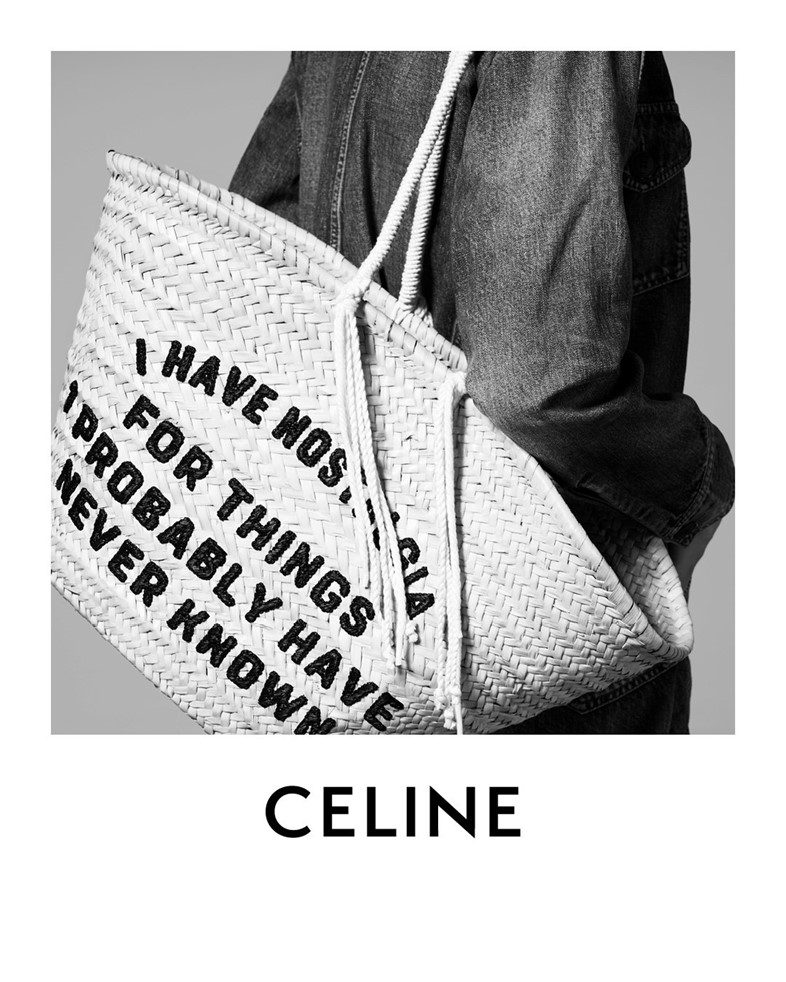

At Sunday night’s Celine show, the curtain fall of the Spring/Summer 2020 menswear season, Hedi Slimane showed flared trousers, paired with the type of cropped continental leathers synonymous with any legend that made a dangerous, iconic record in the 70s – or threatened to. And roomier, rectangular tailoring: the Celine line. But beyond the strong silhouette, a wicker basket flung over the shoulder worked its worth as a totem of the season, embroidered with the declaration: ‘I Have Nostalgia For Things I Probably Have Never Known’. The phrase, along with a ‘My Own Worst Enemy’ ringer tee, worn underneath an encrusted couture teddy jacket, came from New York-born, New York-based artist David Kramer.

It’s Kramer’s work which the season’s invite, a hardbound book you can’t buy for love nor money, was dedicated to. There were more gems: ‘Downhill From Here’; ‘I Am Still Waiting For My Hollywood Ending’; ‘It Doesn’t Get Better Than This’; ‘The Circus Is Running The Circus’; ‘Yesterday Was Better’, ‘There Is No Irony Here’ and ‘Still Betting On The Future’.

It was something of a delight for Kramer to see his self-deprecating inner monologue – albeit already captured on canvas in his own art – paraded on a Paris catwalk. Even more so in a modernist box adjacent to Napoleon’s tomb. Indeed, when we speak, Kramer is still getting his head around it. The artist’s work has been given back to him as a gift in a way that is truly special, almost with the objectivity of distance. Which is not something many get to experience.

As Kramer, who has shown steadily at art fairs and galleries across Europe and North America, explains: “Hedi finds people.” A child of the 70s, his nostalgic art met its match in the collection, which was so pure it fell somewhere between a dream and the haze of memory.

Dean Mayo Davies: So, can you take us back to the beginning of your oeuvre? Was there a particular moment that stands out as a point of creative arrival, when you knew you’d found your language?

David Kramer: Well, it’s interesting – I’ve been working for quite some time in this sort of thing, dealing with imagery and nostalgia for things from the 70s; my youth, fashion, lifestyle and Playboy magazines. Trying to mix that with realisations and contemporary thoughts about how my life maybe didn’t live up to the promise of all of them [laughs]. In the last couple of years I think the work has turned into where we are right now – most of the paintings that Hedi had chosen for the invitation and for the line all are from contemporary work. So all very recent. Really the germination of my ideas came a long time ago, but the look is all in the last two or three years.

DMD: The texts are all your own mediative thoughts, or occasionally fragments of things you hear. Do they occur to you like lightning bolts? Are you constantly writing things down?

DK: Like everyone – I guess everyone – I have inner dialogues with myself and I say things to myself that sometimes make me laugh. Honestly, sometimes I’m out in New York City and I’m talking to friends at openings and someone will say: “Oh you should write that down, that’s like one of your paintings!” One-liners come to me in all forms – I used to write them down in notebooks, now I send myself emails all the time. I’m constantly emailing myself things to remember. I’ve been surprised for years there seems to be some universality to what I write down as self-deprecating criticism of my drawing [laughs]. It’s a tone that people can appreciate and understand in their own ways. And so that’s always been the funny part to me about my work. That other people can seem to really embrace it even though I would like to think that it really does come from a very personal place. That’s what’s so interesting about seeing these phrases now on fashion. It just blows my mind.

DMD: Going back to your earlier work with vintage magazines, what do you make of the idea the collection that you’ve collaborated on with Hedi will one day be seen in its own vintage magazines? Does that cycle intrigue you?

DK: I thought about it in a slightly different way because when I saw the models wearing this clothing – and a lot of the clothing wasn’t specific to my texts or my imagery but was Hedi’s end of the project; the leather jackets, the jeans and everything, the look obviously had a retro or nostalgic kind of feel. So I was thinking to myself that this was actually my current again: all of the subject matter that I had originally looked at was suddenly fresh. In a way as it gets covered in magazines, it’s come full circle. I hadn’t even thought of it in those terms. That’s actually a fantastic way to look at it. I have to start buying a lot of magazines.

DMD: Did the collection remind you of your own youth?

DK: Yes. It does remind me a lot of my childhood in the 70s. Particularly the way the clothing is worn reminded me of the way people looked in a much different era. I typically don’t wear a lot of clothing that has a lot of text on it, advertisements for sports teams or things like that and it’s really great to see the way [the artwork] accentuates the pieces. It looks really fantastic with the text. It will be great to see people wearing this clothing on the streets of New York for sure.

DMD: Your work becomes ‘alive’, beyond the canvas…

DK: Before I met Hedi I would sometimes use my painting as the theme for a t-shirt or a pin that people would wear at openings. At one point I made wine labels and I dressed a bunch of bottles with them. So I always liked interaction. I’d made furniture also and had that as part of my exhibition. I’ve always wanted the audience to be able to participate in the exhibition on a different level than just walking in and viewing the show. This does take it to a whole other level because it transcends the exhibition entirely. It’s pretty dynamite.

DMD: Do you employ the computer in your work or is it more strictly about the hand? I ask because one thing I really got from the collection was that it had a pre-digital warmth which seems almost mythical now – you know this kind of celebration of living before cyber distraction.

DK: Well, it’s funny. I always joke with people that I make handmade memes. And analogue Twitter feed [laughs]. As the work developed, particularly in the last couple of years, I began to understand what the text was going to be before I got to painting. So I began to map out all of the text prior using masking tape. When it’s peeled away, it becomes very sharp and otherworldly, like it was done through a computer – but no computer was used to make these things. It’s kind of a fantastic technique in a way, it does fool your mind. Like many people I’m active on Instagram and the work looks terrific there, looking like they were produced somehow digitally. But they were never, they were just photographed digitally. That’s it.