Preview Morrissey, Alone and Palely Loitering, a new book about the Pope of Mope featuring never-before-seen images by Kevin Cummins

- TextAnother Man

Morrissey is a countercultural hero. Three decades since the release of his debut solo album, Viva Hate, and having just announced new tour dates, a book by Cassell Illustrated has been released, which pays homage to The Smiths frontman. Out now, Morrissey, Alone and Palely Loitering features unseen photos of the musician taken by British photographer Kevin Cummins, who is best known for his images of other musical iconoclasts such as David Bowie, Nick Cave, Mick Jagger and Patti Smith, among others. Here, in an excerpt from the book, Cummins introduces this publication and reflects on the man, the myth and the legend that is Moz.

This book is a celebration of photography and Morrissey.

I first photographed Morrissey in 1983, and the majority of the pictures included in this book cover the timespan from that year through to 1994. Included here also is a series of contemporary portraits exploring the ongoing devotion that Morrissey inspires in his fans, which I have taken as I have travelled around the world meeting people with themed tattoos of their hero. These two things are inextricably linked. Morrissey would not be the cultural figure he is today without his fans. As I state in this book, I have photographed many different musicians but the relationship between Morrissey and his fans appears to me to be a truly unique one.

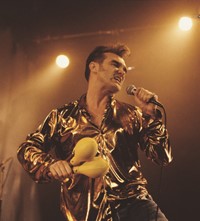

It doesn’t surprise me that Morrissey has become such a prominent cultural figure. I was always a fan and knew immediately that The Smiths had something different to say and something special to offer. Visually, Morrissey was also different from other musicians. He always collaborated with me fully and would come to photo shoots full of ideas. Morrissey has had an astonishing career as a solo musician and I am pleased that I was at Wolverhampton to capture his first concert after the demise of The Smiths. The series of photographs taken there shows the excitement and chaos that reigned at his first live performance in over two years.

There are four main themes in this book that emerge both visually and textually. For the first time, I have written extensively about the art of photography: my influences, how a photograph works, how images can be read, and the absolute importance of visual culture. I have also written about portraiture alongside the studio shots of Morrissey, explaining what makes an articulate portrait and sharing some stories of working directly with Morrissey on some of my better-known images. Additionally, I have also discussed live photography: how it has changed in recent years and the challenges that face a professional photographer working in the unpredictable, if somewhat exciting, environment of the live concert. The book includes photographs from various Morrissey tours – at venues in Dublin and Cologne, Japan and the United States, as well as places in the UK. Finally, in an essay by Gail Crowther, the significance of fans using their bodies as sites of devotion is explored to accompany the photographs of Morrissey-inspired tattoos that I have taken over the last five years. Why do fans have this deep level of devotion to him, and why might they use their skin as a permanent expression of this love?

Revisiting my archive and looking through old frames for this book has been deeply rewarding. Not only can I see how the significance of portraits as historical documents has changed over time, but I was also able to appreciate fully the scope of my work with Morrissey. When I photographed The Smiths for the first time at Dunham Massey, Greater Manchester, for the NME, it was commissioned as a cover feature. Unfortunately, the features editor changed his mind at the last minute and put Big Country on the cover, telling me that he felt The Smiths would never be big enough to be on the cover of the NME. Since that ill-judged pronouncement I have shot more than half a dozen Morrissey covers for the NME, as well as countless book jackets. One of the photographs from that first Smiths session is now in the permanent collection of London’s National Portrait Gallery and the shot of Morrissey that I envisaged for the cover has since been used in numerous magazines, on book covers and on a variety of merchandise worldwide. In fact, visually Morrissey has such a strong iconography today that often you do not need to see his face in a photograph to know that it is him – just a quiff in silhouette or flowers hanging out of the back pocket of his jeans. Even just the backdrop of an empty stage, such as a large portrait of Edith Sitwell or Harvey Keitel, means that the venue is unmistakably Morrissey’s. Building this visual mythology was one of my main aims when photographing Morrissey, and he was one of the few musicians I have worked with who fully understood how and why this was important.

Ultimately, though, this is a book about time, permanence and devotion. Photography, really, in all of its forms is about permanence in one way or another. Things and people come and go. Morrissey and his fans are captured here and preserved in a time that is gone forever. But their connection, those rare, brief moments of meeting, can be revisited, visually at least.

So, paradoxically, this book is about loss and reanimation. And love, too.

Morrissey, Alone and Palely Loitering, published by Cassell Illustrated, is out now