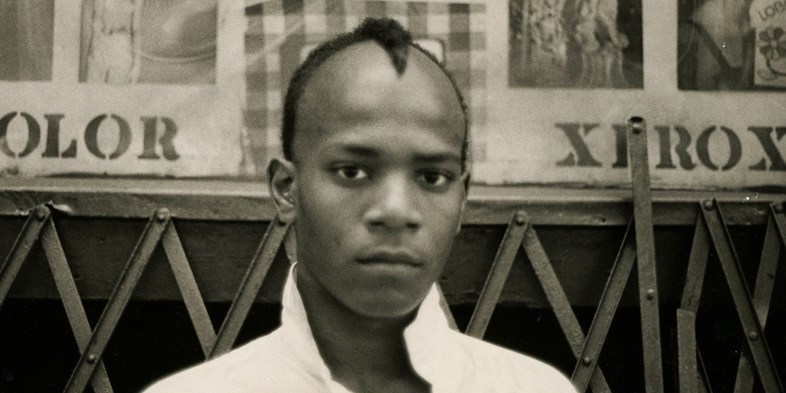

BOOM FOR REAL The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat charts the painter’s rise from teenage Brooklynite to art-world darling

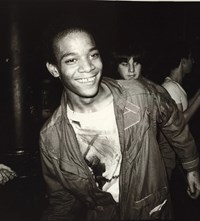

“The age of the white male was already over,” recalls mythical Mudd Club co-founder and curator Diego Cortez early on in Sara Driver’s documentary BOOM FOR REAL The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat, which just had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. Cortez is referring to New York’s late 70s countercultural heyday, as the graffiti, post-punk and hip-hop subcultures were all quickly coming to the fore. This may have been true, but soon-to-be art world darling, Jean-Michel Basquiat, still struggled to hail a cab or get a seat at a high-end establishment on account of the colour of his skin. What’s more, the fervour with which many entrenched art critics and dealers dismissed what they saw as “lowly” and “pathetic” art smacked of systemic racism.

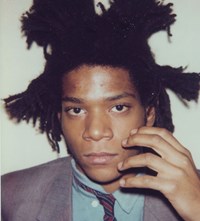

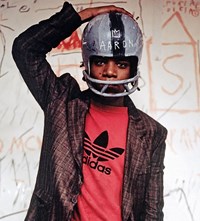

Those occurrences didn’t just fuel the dreadlocked Brooklynite’s inimitable, sample-loaded art – from his politically charged SAMO© graffiti scribbles with Al Diaz to the glorious black figures he’d splash across large canvases. They also thrust him into the spotlight at supersonic speed, with Vanity Fair anointing him “America’s first truly important black painter” only a few months after his tragic, heroin-induced death at the age of 27.

Driver, who was part of the NYC downtown cinema scene at the time with her partner Jim Jarmusch (she also produced his Stranger Than Paradise and Permanent Vacation), focuses on a very narrow period (late 70s to early 80s) during which she moved in the same circles as the fledgling Basquiat, who was still honing his untamed, childlike signature. Alternating between talking-head testimonials and archival footage, BOOM FOR REAL revisits the very politicised, emancipated and rebellious circumstances that stoked Basquiat’s creative fire. For example, the poetic and often confounding tags he scribbled across SoHo and Lower East Side buildings under the SAMO© moniker (derived from “same old shit”) echoed the city’s booming graffiti culture and were inspired by reading Burroughs and crime novels. But Basquiat took the concept further by satirising consumer culture and poking fun at neighbourhood youths who’d adopted bohemian ways on their parents’ dime.

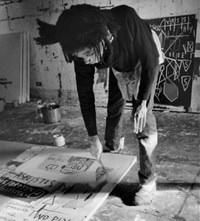

From hip-hop pioneer Fab Five Freddy to graffiti legend Lee Quiñones, BOOM FOR REAL presents real insight into how a fledgling and ever-elusive Basquiat was already living in the fast lane, gaining a rock-star entourage practically overnight while becoming NYC’s irresistible poster boy for creative dissent. Before the charismatic artist began donning paint-stained suits with hundred-dollar bills crammed into the pockets, Driver alludes to his enduring fascination with anatomical drawings and textbooks, Leonardo Da Vinci and Cy Twombly, arcade games and hip hop culture, and bebop fathers Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. While so many struggled to infuse their art with a sense of urgency, Basquiat’s output was seen as a strikingly immediate reflection of its time. Driver zeroes in on the moment that changed everything for him: a 1981 New York/New Wave show at PS1 in Long Island where he was given a whole wall to showcase 20 paintings.

The film jumps from Gray, the experimental band he co-founded with Michael Holman (and which included Vincent Gallo) to the entirely hand-painted Man Made clothing label he collaborated on with designer Patricia Field. Whatever Basquiat would bring in from the street, he’d spin with his singular vision and vigour. “He was like a filter,” says Jarmusch in the documentary. “A true investigator of ideas, visual language and music.” Basquiat was fully committed to Warhol’s polymath pursuit: dabbling in a dizzying amount of creative endeavours and never hitting the brakes on his self-expression.

Of course, Driver hints at the alarming cocaine and heroin culture that would ultimately get the best of the rock-star artist, a mere seven years after selling his first painting. But the aim here is to track his vertiginous ascent, not his untimely demise. Hearing so many first-hand accounts of a “magnetic” and preternaturally gifted Jean-Michel from friends, acolytes, collectors and lovers only feeds the myth, to be sure. But BOOM FOR REAL also serves as a nice companion piece to Julian Schnabel’s 1996 Basquiat and Tamra Davis’ 2010 Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child.

Earlier this year, his painting Untitled (1982) sold for $110.5 million, while this week the first British retrospective of his work opens at the Barbican Art Gallery, demonstrating that interest in this artist remains piqued. And though Driver’s documentary doesn’t put an end to the mythologising of Jean-Michel, it does provide a fascinating glimpse into the underground scene that inspired him, the community of misfits that embraced him and the social climate that allowed him to thrive, in a recklessly teeny window of time.

The Basquiat: Boom for Real exhibition is at the Barbican until 28 January, 2018.

Sara Driver’s BOOM FOR REAL The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat next screens at the 55th New York Film Festival.