Filmmaker Eugene Jarecki lifts the lid on his new film The King, which explores the current state of America via the life of Elvis Presley

- TextZoe Whitfield

“When the film first premiered at Cannes, I was still trying to process what this new moment meant,” explains filmmaker Eugene Jarecki, speaking over phone from Greece. “The election of the current president; what it meant for the film, whether it changed my narrative.”

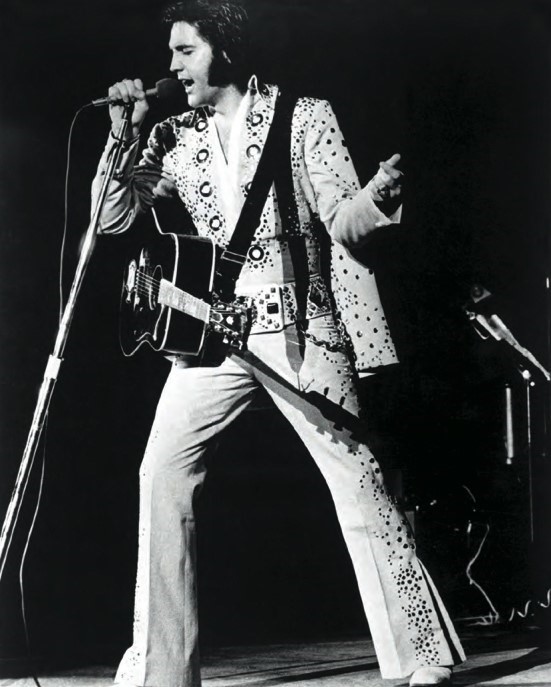

Moulding The King (previously titled Promised Land), “long before this person announced he was running for office,” Jarecki’s latest picture explores the current state of America via the life of Elvis Presley, delving into the pair’s fundamental connection through a road trip in the music icon’s 1963 Rolls-Royce Phantom V. “The car is a natural vessel for that kind of study of misplaced kingship,” notes the director, who has previously picked up the Sundance Grand Jury Prize for Documentary for his films The House I Live In (2012) and Why We Fight (2005).

Audibly animated throughout our conversation (the phone vibrates as he discusses everything that is wrong with America today, namely “cutthroat capitalism using democracy as a fig leaf,”) the finished film is as unique as its protagonist: a figure as synonymous with the US as Coca Cola who never performed beyond its borders (which is hard to imagine today).

Featuring cameos from Public Enemy’s Chuck D, Elvis’s former girlfriend Linda Thompson, and Another Man cover star Ethan Hawke – along with vintage footage of Presley himself – The King provides a thorough examination of American culture, leaning into discussions around race and cultural appropriation. Here, Eugene expands on the metaphor of this film.

What was your relationship to Elvis, prior to making The King?

Eugene Jarecki: I’ve always loved Elvis – in a lot of ways and at different points of my life. If you grow up in America and you’re a sensitive person, your perspective on many elemental parts of our culture… you grow in relation to them, so I’ve grown in relation to Elvis.

What was your starting point for the film?

EJ: I saw an allegory between Elvis and America, and thought it an opportune time to look back to him; to trace his rise and demise, and see tremendous metaphoric implications for the story of America. Elvis struggled with premature power as America has struggled, a young country with an extraordinary amount of influence. And Elvis died young, undone by the fact he had reached out for all manner of quick fixes – consumption, materialism, vanity – and of course, America is a country defined by quick fixes.

“Elvis struggled with premature power as America has struggled, a young country with an extraordinary amount of influence. And Elvis died young, undone by the fact he had reached out for all manner of quick fixes... and of course, America is a country defined by quick fixes” – Eugene Jarecki

In terms of the film’s guest appearances, did you set out with any shortlist?

EJ: You can’t make a film about Elvis in America without certain people who loved and worked with him. But you can’t make a modern film about Elvis without Chuck D, and a way of looking at Elvis that doesn’t come from proximity. Also, it’s about the allegory of Elvis, [so] you needed people who can speak to America from different vantage points. I knew Elvis’s rise and fall would serve as a structural arc for the film – and that meant we were going to Tupelo, Memphis, Nashville, New York, Las Vegas. In a lot of cases, we would roll into town like a 1950s A&R guy and people would say, ‘if you’re doing something about Elvis you’ve gotta meet…’ The luck was more extraordinary than the plan.

How did people react?

EJ: People understood the metaphor very powerfully, but you can’t explore a metaphoric idea and end up with anything other than an impressionistic, poetic exploration. We weren’t sure how to give the film the structure it needed, then we learned that Elvis’s 1963 Rolls-Royce was about to go up for auction and thought, ‘what if we made a great American road movie out of this poetical reflection’, and the movie took on a more complex structure.

What was the reaction to the Rolls?

EJ: On the second day of filming we had the legendary John Hiatt join, and he showed up looking the part. I thought ‘wow, this is about to be a rocking afternoon’. I look in the back [of the car] and I notice that he’s crying his eyes out. I said ‘did somebody do something?’ and he said ‘I just sat down in this car and was overwhelmed by what he must have felt, this guy was just a country boy from Tupelo’. You could feel his levels of compassion as he sat crying.

How did your idea of Elvis change during shooting?

EJ: I learned an idea about Elvis that people really need to take on, because it speaks to the American predicament. I was saying to Elvis’s friend, Jerry Schilling, that Colonel Tom Parker [Elvis’s manager] had destroyed Elvis in the same way that capitalism was destroying the hopes and dreams of the American people. He said, ‘I agree capitalism is destroying American democracy, but where do you get this idea that the Colonel destroyed Elvis? Elvis loved the Colonel like a father and he loved what the Colonel did for him’. He taught me that if I’m to understand an analogy between Elvis and the American people, I have to understand that Elvis was both victim and protagonist, like the American people are now.

Elvis and his trajectory are wholly unique. Does anyone come close today?

EJ: The purity of focus Elvis had is unattainable today because we live in a society of a million references: once you live in a Facebook, Instagram, Twitter era, everything is a retweet. It’s difficult to imagine the kind of originality and authenticity that came from Elvis’s accidental marination in black culture as a young boy from Mississippi.

What do you hope audiences take away from the film?

EJ: Elvis is a cautionary tale, both for America and for Britain, because what happens on a Monday in America, happens on a Wednesday in Britain. What we are seeing is the tragic manipulation of the public by those in positions of power for political convenience. The public got its heart broken, and when you get your heart broken it makes you desperate. In this moment, some measure of the public reached out for anyone saying something different, and they got somebody who happens to have been a charlatan, and preys upon their vulnerabilities like a terrible rebound guy for an abused person, and they’re getting deeply hurt. What do I want people to take away? Stop the abuse, stop your own self seduction.

The King is released in cinemas across the UK and Ireland by Dogwoof on Friday, August 24