From David Bowie to Iggy Pop and Nick Cave, Berlin’s Hansa Studios captured the spirit and darkness of its hometown in each one of its records

- TextTom Connick

Recording studios rarely get a namecheck. Little more than a footnote on most albums’ record sleeves, from Abbey Road to Hollywood’s Sunset Sound, there’s a romance to the recording booth that often goes unchecked in this era of bedroom production. But while those iconic musical landmarks may stake claim to hosting all manner of timeless records, few spaces left a mark on its conveyor belt of occupants quite like Germany’s Hansa Studios, the story of which is told in Sky Arts’ new documentary Hansa Studios: By The Wall 1976-1990.

From David Bowie’s Low and Heroes, to U2’s Actung, Baby!, via Iggy Pop, Depeche Mode and Nick Cave, and onto R.E.M.’s final album Collapse Into Now, Hansa was the birthplace of some of the 20th century’s most defining musical works. The film’s producer and director Mike Christie grew up on a diet of that output. Reading stories of the West Berlin studio’s magnetic appeal, it became ingrained in his development as a music fan – through the discovery that Bowie’s Heroes was recorded there, Christie went on to become a lifelong fan of the Thin White Duke, unearthing more of Hansa’s history as he went.

“When you’re making these films, sometimes you don’t realise you’re waiting for the opportunity to tell a particular story,” he explains. Called upon in the wake of Bowie’s death to produce something around his ‘Berlin trilogy’, Hansa became “the elephant in the room. The more we looked at the story of Bowie, the more we kept thinking, ‘No one has told the story of this place…’” Spurred on by the success of Foo Fighters’ Sound City docu-series, the project was born: “You’re thinking, ‘Hang on, that’s essentially the most fascinating studio story of all, sitting there, waiting to be told’,” Christie enthuses today.

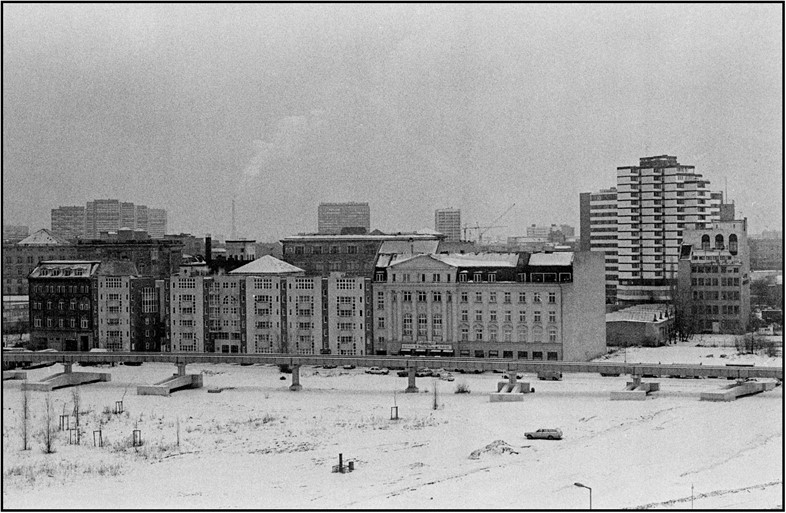

“... a stone’s throw from the Berlin Wall, the Hansa Studios of the 1970s was an imposing figure; its mixing room overlooked by turrets packed with armed guards”

Perched on the edge of a bulldozed wasteland and a stone’s throw from the Berlin Wall, the Hansa Studios of the 1970s was an imposing figure; its mixing room overlooked by turrets packed with armed guards. That scary, scorched aesthetic soon proved fertile ground for Hansa’s evolution though, as its producers sought to move away from German Schlager music – a sterile, cabaret-esque style of pop, described by one of Hansa’s producers in the film as ‘um-tata’ music.

Amongst their many foreign saviours was one Iggy Pop, who recorded debut solo album The Idiot there in 1976, with Bowie behind the producer’s desk. That iconic drum beat that kick-starts Lust For Life owes its echoey sound to the reverb of Hansa’s walls, while Iggy’s scratchy vocals were recorded – at his insistence – through an in-house guitar amp. That sense of exploration was key. “So many of these defining records were made – effectively – by tourists,” says Christie. It’s that otherworldly feeling which formed such an integral part of Hansa’s magnetic appeal. From the nightclubs on the studio’s doorstep (most notably depicted on on Nightclubbing from The Idiot), to the dark, twisted soundscapes of Germany’s burgeoning industrial and noise scenes, buoyed by bands like Einstürzende Neubauten, Hansa became a beacon for those looking to unleash their musical freedom.

“Hansa soon became a pilgrimage site for those looking to unleash their inhibitions”

“This is a city that really had no limits,” says Christie. “Anything went in Berlin. It wasn’t quite lawless, but it had an extreme freedom within it. So, on one hand you’ve got this city where anything goes and which is cheap and incredibly liberal. And on the other hand you’ve got an incredibly vast recording studio, that is owned by a company with masses and masses of money.” Hansa soon became a pilgrimage site for those looking to unleash their inhibitions – Depeche Mode owe the dark sound of post-pop years to the studio, while Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds formed in the wake of previous band The Birthday Party’s dissolution within its walls; The Bad Seeds returned to record there just months after The Birthday Party splitting. “It had the same DNA as Berlin, it had few rules; it was a really blank canvas where people could try anything,” says Christie. “There was money for equipment, and there was space – there was no shortage of space. And there’s no neighbours upset because you’re in the middle of a wasteland. So, you’ve got this incredible kind of playground. You’ve got all this incredible tension and incredible, weird static kind of post-war Berlin, nothing having had been developed. Everything sort of frozen in time.”

That static seems to flow throughout Hansa’s output. Throughout the film, artists talk of a ‘Hansa sound’, one defined by darkness and industrial textures, but also by creative liberation. “Tupelo sounds very strongly of this room,” says The Bad Seeds’ Mick Harvey in the film, referencing the band’s noir-punk 1985 single, while others applied Hansa’s audible energy to their work more literally: Depeche Mode sampled parts of the building itself on their Some Great Reward LP, right down to the sound of a pebble rolling across the studio’s windowsill. It gives the recording space and its output a haunted air – one which Christie is fully enamoured with: “The main room, there is no doubt, it absolutely had a sound,” he says. “And everyone said that. And all those artists who came back and returned for the first time all pretty much did the same thing: they all clapped, just to hear the sound. You know, half a dozen people did that in that main room. There’s something magical about the dimensions of that room and what it’s made of.”

“... artists talk of a ‘Hansa sound’, one defined by darkness and industrial textures, but also by creative liberation”

Whatever form that magic took, Hansa’s signature is unmistakable. From the industrial underworld of Einstürzende Neubauten and their peers, which in turn inspired Depeche Mode’s move into strenger sonic textures, and onto its 80s mainstream heyday, culminating in U2’s arrival on the day of Berlin’s reunification and subsequent writing of One, it’s a sound of hope and hedonism, all wrapped up in a darker-than-average package.

Today, Hansa remains partially open for business. Despite the collapse of the Wall prompting a slump in its success during the 90s, the building remained resolute, prompting a 21st century revival. In more recent years, it’s played host to everyone from Supergrass, to Snow Patrol, to KT Tunstall and R.E.M., who played their last-ever show in Hansa’s great hall for 25 friends as they recorded Collapse Into Now – in the film, frontman Michael Stipe speaks of the intense emotions he felt bleed into that room as their final chords rang out.

It’s Hansa’s spirit that rings most true in By The Wall 1976-1990 – one that Christie still feels enamoured with as his near two-year-long project comes to a close: “Even though they were adopting and embracing new technology as they went,” he says, “they managed to preserve a spirit of creativity that pre-dated a period of all the plug-ins and apps.” As the music world moves forward into a new technological age, with artists able to produce entire records on their smartphones if necessary, Hansa stands tall as a marker of what a truly timeless studio setting can offer. “That space wasn’t a museum, wasn’t an antiquity – it was an incredible laboratory,” Christie beams. “At the end of the day, there are some things that are almost... spiritual.”

Hansa Studios: By The Wall 1976-1990 will be broadcast on Sky Arts on January 10.