As Salvador Dalí’s set of tarot cards is re-released alongside a new book about the deck, a look at how the artist repurposed figures from art history for his take on the traditional tarot characters

- TextEmily McDermott

Hearing the word ‘tarot’ can quickly conjure thoughts of esoteric mysticism and summon the images of a magician, devil or fool, yet tarot cards were initially developed around 1430 by Italians to play conventional games. It wasn’t until the late 18th century that divination entered the picture, and not until the 1970s, with the rise of the New Age movement, that the occult associations took hold of the narrative. Writers such as T.S. Eliot had already incorporated tarot into their work, but at this time a slew of creative icons began referencing tarot, with some artists even making their own decks. The most famous set of cards produced during this time is arguably the Tarot Universal Dalí, by the Surrealist legend Salvador Dalí. Although his 78 original gouaches are something only a collector can dream of, the long sold-out limited-edition printed deck is being re-released this month by Taschen with an accompanying book, Dalí. Tarot, written by tarot expert Johannes Fiebig.

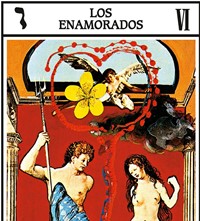

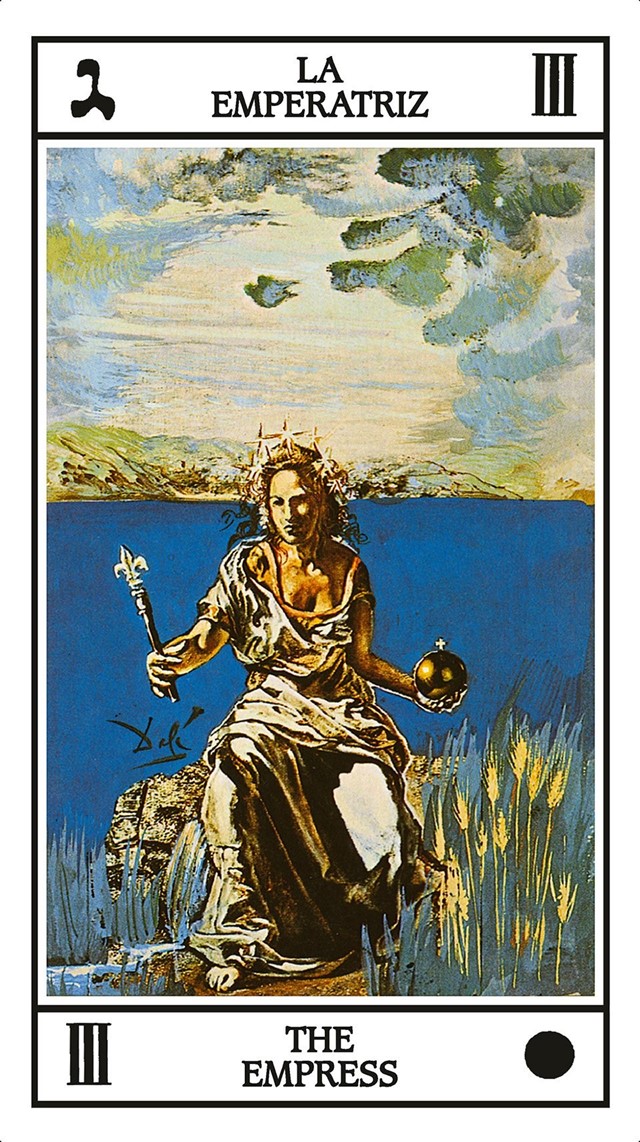

For his deck, Dalí created new artworks for each card, nearly 90 per cent of which were made by drawing or painting over and collaging existing masterpieces. “What’s special about Dalí’s tarot is that he didn’t make any new symbols or signs,” Fiebig says over the phone. “He used the old masters to say, ‘This is also tarot,’ and to open our eyes to the fact that there’s a deeper meaning in these artworks, a wider reality.”

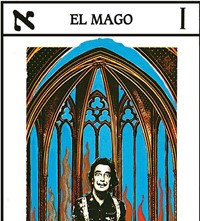

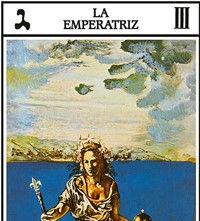

On the Four of Swords, for example, the figure of Jean-Paul Marat, painted by Jacques-Louis David in The Death of Marat (1793), is extracted from his surroundings, placed against an eggshell white background, and his limp, lifeless hand now seems to hold the blade of a blue and white sword, while three more stand behind him. Meanwhile, a card like the Queen of Cups mixes references from both antiquity and modernity: a cartoonish yellow crown is drawn atop the head of the eponymous figure in François Clouet’s Elisabeth of Austria, Queen of France (c. 1571), her right hand resting on a matching goblet. Three semi-transparent strokes of blue were then used to add a moustache and goatee to her face, a nod to Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. (1919), in which he added the same facial features to Mona Lisa. On the cards The Magician and The Empress, Dalí and his wife, Gala, are transformed into the two titular figures. When it comes to reading cards with the Tarot Universal Dalí, such references make it clear that reality, and therefore one’s identity, is never fixed.

“It is important for every human to have their own emotional sovereignty, meaning that you can combine what are traditionally male or female roles,” Fiebig continues. “You can combine gentleness and softness with determination and strength. And in these cards, in these collages of old masters, Dalí has drawn that out.”

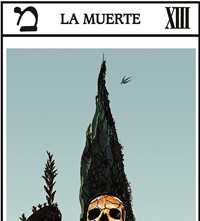

In addition to historical art references, there are also three recurring motifs to be found throughout the deck: butterflies, traditionally representative of the psyche; crutches, which Dalí apparently believed had a double meaning, representing the dualism of consciousness and unconsciousness, as well as of inner and outer worlds; and shadowy traces of human figures, which can be seen as ghostly re-assertions of the specific card’s focal points. Understanding what these symbols generally signify will help you interpret the cards’ meanings, yet, like the art references, it is important to remember that your personal point of view is equally as important. As Fiebig explains: “When reading cards or interpreting dreams, one level of it is about cultural history, and the other is about how you see it personally.”

In fact, when asked what a user must understand about Dalí to use or read cards with his tarot deck, Fiebig instantly replies, “nothing”. The most significant thing to know about the Tarot Universal Dalí is that it is not only a collection of cards, but that it is, perhaps more importantly, a singular Dalí artwork – which, like all art, will always be viewed and understood through the viewer’s personal lens. “In Europe we say that the cards are a mirror,” Fiebig says. So, if you choose to read these cards, “you must ask: What do you see in the card? Do you like it, or does it scare you? Where do you see yourself in the picture? Those are the questions, and this is not fortune telling. Someone else can’t look in the mirror for you.”

Dalí. Tarot is available now, published by Taschen.