Off the back of the label’s collaboration with Public Enemy, we explore the story behind the hip hop group’s seminal album Fear of a Black Planet

- TextKemi Alemoru

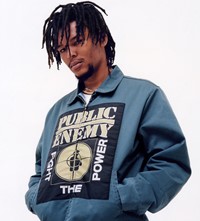

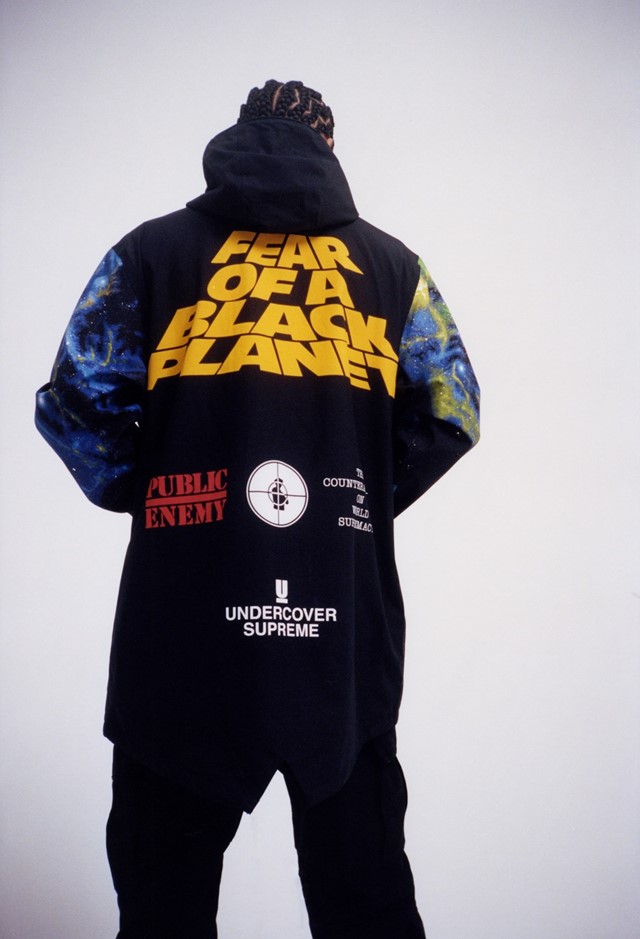

Supreme has tried to emblazon its logo on just about everything. And while you may struggle to find a deeper meaning in things like its branded clay brick, the label’s collaboration with Undercover and Public Enemy, unveiled on Monday, sees the streetwear heavyweights revisit Fear of a Black Planet – one of the most socially-conscious albums in hip hop history.

As Public Enemy’s frontman Chuck D explains in the collection’s promotional preview, he and fellow performer Flavor Flav worked to create an album that “laughs at the fallacy of race”. It was born out of urgency. New York in the 80s was hit by a wave of crime after drug addiction gripped its communities. The city was struggling financially; wealthier white people left in record numbers, and those who were left blamed the problems on minorities. Out of this pain and struggle hip hop was born – but so was a renewed fear of blackness.

When traditional news outlets went into a frenzy, demonising crack and blacks, and sensationalising New York’s desperate inequality by renaming it “a rotten apple”, Chuck D famously told a crowd in 1989 that musicians had replaced headline news among young African Americans. “Rap music is the TV station that black America never had,” he explained. Fittingly the 1990 album and its anti-establishment message came to define the next era of rap, truthfully detailing the African American experience.

Of course, the record is best known for spawning the protest track Fight the Power, a roaring soundtrack for resistant youths. But what earned the album a spot in the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry is how it covers an impressively broad spectrum of social anxieties black people faced at the time. From the general fear of a multicultural society in the title track, to very specific gripes the group deconstruct in their lyrics.

In Burn Hollywood Burn, for example, they enlist the likes of Ice Cube and Big Daddy Kane to bemoan the lack of roles for black people on-screen – something that remains relevant to this day. While in 911 is a Joke, they criticise the apathy of the emergency services towards the black community. But even though the visuals for the track, which reached number one on the Hot Rap Singles chart, are comical, the lyrics reveal a deep mistrust in the government. The song serves as a public service announcement to African Americans, that their country would rather let them die than help them with its increasingly squeezed resources. “A no-use number with no-use people,” raps Flavor Flav. “If your life is on the line then you’re dead today.”

Throughout the tracks, you can hear the claustrophobia of racism clashing with black culture, and the group’s controversial ideologies. It bleeds through the entire album. Most of its 20 songs include dozens of samples, almost acting as a sonic syllabus of African American history. The group riffs over soundbites from news segments and speeches, while weaving in melodies from funk classics and black superstars like Michael Jackson and Bob Marley – all of them bound together by the heavy production of The Bomb Squad collective, known for their cacophonous style. And while this gave the group a distinct sound, by including interviews of concerned white people attacking the group’s brash demeanour they also gave themselves a voice.

All of these elements came together thanks to the curatorial eye of Chuck D (also a Bomb Squad producer), who drew on a variety of inspirations and collaborators to document the climate of hostility. You see it in the symbolism in the album artwork created by NASA illustrator B.E. Johnson enlisted by the ambitious rapper. Johnson wrote about his fond memories of working with the group – namely his run-ins with Chuck D’s very specific vision. “[It was a] great concept and I immediately saw where he was going with it,” he wrote, explaining the rapper’s vision of having an ominous black planet eclipse planet earth. “But, being a physicist, I knew that just wouldn’t fly. [You] can’t have something in the close foreground that is the same angular diameter as something in the background and have the former completely shadow the latter.”

Things worked out for the best though because that scientific impossibility only works to highlight the delusion of racism and the undue fear of blackness the album addresses. And while there may well be criticisms from people that believe Public Enemy’s anti-establishment message about poverty and oppression is incompatible with the culture of exclusive streetwear, Supreme and Undercover have proved their engagement with the album’s themes and will be donating a portion of the proceeds to the ACLU – a civil liberties organisation that protects citizens rights to protest and battles in court on behalf of those under threat. The message of the radical album lives on, and it is this that streetwear fans will be branded with when the collection drops.

The Supreme x UNDERCOVER x Public Enemy collection will be available in-store NY, Brooklyn, LA, London, Paris and online from March 15th. A portion of the proceeds from the collection will be donated to the ACLU