Unravelling the Myth of 1990s Photographer Davide Sorrenti

- TextJack Moss

As a documentary about Davide Sorrenti arrives in UK cinemas this weekend, we speak to filmmaker Charlie Curran about the photographer’s complex legacy

See Know Evil, a recently released documentary by first-time filmmaker Charlie Curran, recounts the life of prodigious fashion photographer Davide Sorrenti. His early death in 1997 aged just 20, then wrongly attributed to a heroin overdose, would mark the symbolic end of an era provocatively titled “Heroin Chic”, named for the numerous photographs of seemingly strung-out, waifish models on city streets or in unnamed hotel bedrooms which appeared in fashion magazines like The Face and Detour in the mid-1990s. A New York Times article by Amy Spindler likened his death to “a bomb going off”. “Even if it was a bomb detonated in the home of the person making it, it didn’t dispel the impact,” she wrote. “The period of denial is over.”

And so it went: Davide Sorrenti’s photographs, alongside countless contact sheets, collages, doodles and illustrations, were boxed up and stored in his mother’s apartment in New York City, while fashion magazines touted a wholesome ‘new era’ and supermodels to match (a 1999 American Vogue cover, featuring Gisele Bündchen draped in a crotchet blanket, ran with the tagline “The Return of the Sexy Model”). Anna Wintour – in a clip which appears in the documentary – declared the era “pathetic”; Bill Clinton, “ugly”. “Fashion photos in the last few years have made heroin addiction seem glamorous and sexy and cool,” he said in May 1997. “The glorification of heroin is not creative, it’s destructive.” Davide was a cultural lightning rod; then, for the next two decades, all but disappeared.

In the years since, the Sorrenti family itself has remained prolific: Francesca Sorrenti, Davide’s mother, arrived in New York from Naples, Italy with her three children in the early 1980s. A decade later, they were being dubbed the ‘Corleones’ of fashion photography; beside Davide, the youngest of the siblings, there were Vanina and Mario, both photographers, like Francesca herself (she began working in New York as a stylist, then later became a photographer, which she continues to work as now). Mario Sorrenti is perhaps the most known, an ex-model who found renown for his intimate portraits of a young Kate Moss – his then-girlfriend – on the precipice of stardom, leading him to him shoot her for Calvin Klein’s infamous 1993 Obsession campaign. Both Vanina and Mario continue to shoot for numerous publications and fashion houses today.

The entire Sorrenti family are interviewed in See Know Evil, which held its UK premiere in London yesterday, and will tour Everyman cinemas across the country this weekend. It is directed by Charlie Curran and began far and away from New York, in sleepy Savannah, Georgia, where the then-20 year old was studying at the Savannah School of Art and Design. “I was going through this moment of teenage angst and I felt like I, and everyone around me, was making just student work. I just wanted to know: How do you make capital ‘A’ art?” he says over the phone from New York, where he has since moved. Then, a moment of serendipity: one afternoon, in the library, he found a copy of Rebecca Arnold’s Fashion, Desire, Anxiety left out by another student. “I opened it by chance and there was this chapter about Davide and the kind of moral panic in fashion photography in the late 90s,” he says. “I saw his work that day for the first time I was like: wait, he was 20 when he made this? I wanted to know how it was that another 20-year-old was able to make images with that kind of gravity.”

And so a seven-year project began, which would see Curran travel across the country to interview those who knew, or encountered, Davide while he was alive. “It started as a kind of investigation, I just wanted to figure it out,” he says of the initial impetus. “Because of all the controversy no one else had got a chance to hear his stories, he had so much work but his family had shut off all access to it.” He emailed Mario and said he wanted to make a student film about his brother. Mario’s stepfather, Steve Sutton – who is also Mario’s business manager – replied: they were about to go on holiday, but they would be in contact when they were back. “I don’t think that I could’ve made this story if I was much older than Davide when I started, I think that a lot of what allowed me to make it was my naivety, and enthusiasm,” Curran says. “I basically didn’t know any better.”

Francesca was initially reticent to talk: she had been approached by numerous people prior to Curran, and had previously felt unwilling to return to Davide’s story. But Curran was persistent, and so she agreed to meet him in New York. “I just showed up and was like: this is why it is important,” he says. “I told her I wanted to get to the heart of what happened, for kids with similar paths to have this story. I wanted to kind of ‘de-glamourise’ it, and the way the story has previously been told; the way Davide has been portrayed in the industry. Luckily, she totally got it. She wrote me a list of like, 23 names, and said if you interview all of these people, you have the story.”

Curran flew around the country – funded initially by his uncle’s air miles, then by a Kickstarter campaign – interviewing not only the Sorrenti family, but numerous people close to Davide, including photographer Glen Luchford and actresses Milla Jovovich and Jaime King, who both worked as models in the 1990s (King dated Davide in the final years of his life). While in New York, Curran would spend hours in Francesca’s apartment, scanning image-upon-image from Davide’s archive in her spare bedroom. “She was insistent I had to scan it in the house because she didn’t want the stuff to leave,” Curran says. “I spent like a month doing it on this giant, large-format scanner. She just made me a key and I would just go, day and night, scanning and scanning.”

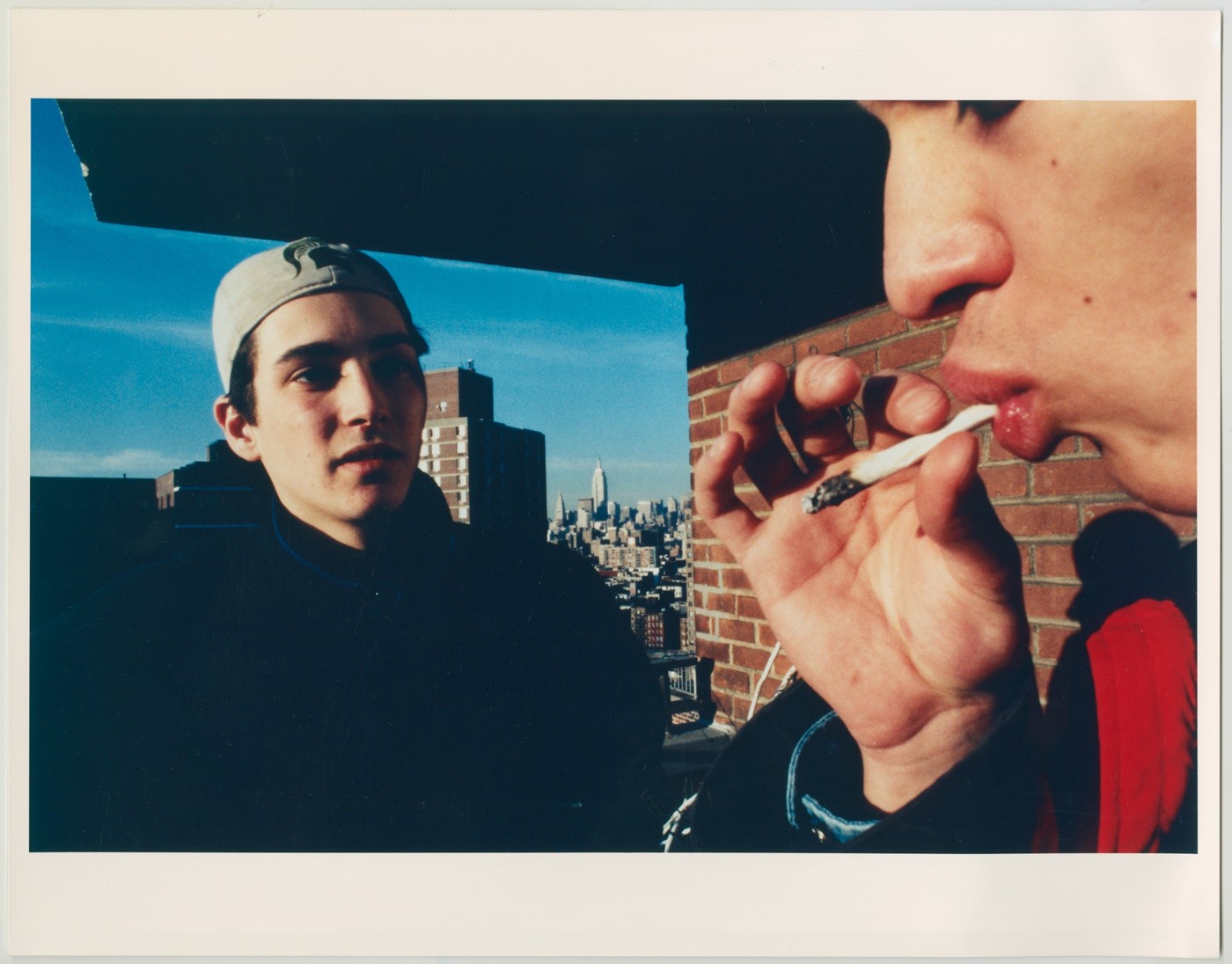

Those images provide much of the backdrop for See Know Evil, alongside various archive clips, some of which were taken by his sister Vanina when she was in her early twenties. The photographs themselves – which had appeared in magazines i-D, Detour and Interview, alongside personal snapshots of King and friends in New York – capture something fleeting, and ephemeral. King smoking, in a flare of red light, eyes distant; Jovocich lying prone on her apartment roof, one arm hovering off the edge, as lines of New York taxis move in concert below. They are stripped almost entirely of the excess of the 1980s: “The pendulum swung back to minimalism,” Curran says, “people wanted to explore this kind of humanistic, realistic portrayal of fashion.”

Sorrenti’s death was wrongly attributed to a heroin overdose in the press: in fact, he suffered with a rare blood disorder, known as Cooley’s Anaemia, which would eventually lead to kidney failure (though heroin was found in his system). He had suffered it since childhood, and part of the reason Francesca had moved to New York was for his treatment, which involved long, uncomfortable evenings spent strapped up to various drips in hospital. See Know Evil reframes Davide’s short life as one of pain, where energetic, fertile stints of photography were followed by days of fatigue, spent in bed. “The first thing that shocked me was that he was sick, you don’t read about that in the press,” says Curran. “I think that when you understand this illness and how he was forced to live and see the world, for me that changes everything. I can’t imagine having to hook myself up to machine with a needle every night as a kid. That sounds horrible.”

“Realising the significance of events when you are in the eye of a storm is an underestimated talent,” reads an article on Davide’s legacy featured in the October 2000 issue of Dazed. Beyond his fashion images, Davide captured New York, too, at a moment of change: kids at Washington Square, evenings at run-down apartments on the Lower East Side, a city pre-gentrification, pre-Giuliani, pre-“the adult Disneyland” Curran calls the city today. He always knew his life would be short, and the photographs capture this impermanence: “Anyone who feels like there’s an expiration date on their life,” says King, “will constantly shift between melancholy and wanting to live life to the fullest.” The sheer volume of images he produced seem testament to this: they were his attempt to grasp the world and hang on to it, to leave his mark.

“I mean we all know that we’re going to die at some point,” says Curran, “but to just have it constantly reminded, it’s just such a different take on life. Instead of wallowing in pity he really celebrated life, and was just going for it. He was fearless. It was like an explosion of creativity. I feel like his story is the oldest of all time: he’s watching the clock run out, and trying to make art while he can.”

The film ends with footage of Davide on holiday in Mexico with his family. His behaviour has been increasingly erratic: he has arrived in Mexico from Los Angeles where he was with then-girlfriend King, herself addicted to heroin at the time, who says in the film that week he was “like another being, like a part of him was leaving”. In grainy, sunlit footage, he runs in and out of the waves, his scarred, childlike body bouncing in the surf. Francesca says she remembers him catching a fish, and giving it to one of the local women on the beach, asking her to hold it for a photograph. It would be the last photograph he ever took: the day after, in New York, he was found dead in his apartment. The fish stares upwards from the woman’s hands; fierce sunlight illuminates the frame. It is ordinary and extraordinary at once, encapsulating the kind of joy you might experience seeing the world for the first, or last, time.

“When you smell roses, when you know you are only there for another few weeks,” photographer Glen Luchford says in See Know Evil. “Then it’s going to be the most incredible thing you’ve ever smelled in your life.”

See Know Evil is on at Everyman cinemas this weekend. This evening, it is shown at Hampstead Everyman, alongside a Q&A with Francesca Sorrenti. For more information click here.