As the Barbican’s blockbuster exhibition Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography opens, a look at the extraordinary career of Rotimi Fani-Kayode and his lasting impact on image-making

“On three counts am I an outsider,” wrote Nigerian photographer Romiti Fani-Kayode, “in matters of sexuality; in terms of geographical and cultural dislocation; and in the sense of not having become the sort of respectably married professional my parents might have hoped for. Such a position gives me a feeling of having very little to lose.”

Fani-Kayode was just 34 when he died, suddenly and unexpectedly, in 1989, the victim of a heart attack following an Aids-related illness. He left behind a body of work that was unashamedly black, African, and gay, showing a tender, sensuous, fantastical image of masculinity, that was always thoroughly political. He worked in an often hostile environment and following his death his work was exhibited only rarely. His portraiture, however, makes an invaluable addition to Masculinities: Liberation through Photography, just opened at the Barbican Centre.

Fani-Kayode was born in Lagos in 1955 to a politically powerful family. His father’s role as a Yoruba chief, lawyer, and statesman caused them to flee the country for Britain in 1966 at the outbreak of civil war. Fani-Kayode was brought up in Brighton before moving to the USA to study at Georgetown and the Pratt Institute, where he met Robert Mapplethorpe and began to develop his photography practice. In 1983, he returned to the UK and made a home in Brixton, south London, with his lover and collaborator Alex Hirst.

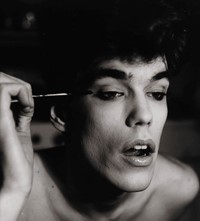

Central to his life and work was his understanding of himself as a marginal and estranged figure. “He’s creating a black, queer aestheic full of power, it’s about cultural dislocation,” says Barbican curator Alona Pardo. “He is self-imaging, self-identifying, self-defining, and that was a radical political gesture at the time.” Fani-Kayode saw his various identities – black, African, gay – as interwoven, yet he never played down the complexity of being pulled and pushed between these often contradictory positions. He wrote that his homoerotic pictures sold well because of his “black ass and black dick”, that art galleries and the press were happy with his “ethnic” pictures – less so the gay ones – and joked that Lagosians would riot before they accepted his “decadent western values”.

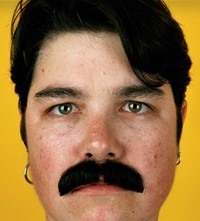

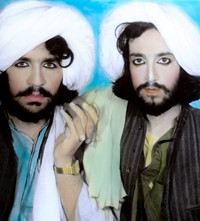

Fani-Kayode directed his work to questioning the entrenched ideas of art and society; mixing satire with erotica, he parodied the Catholic church and the history of western ethnographic photography while introducing Yoruba spiritual ideas and visual motifs. The image-maker compared his own work to that of the Osogbo artists of Yorubaland, Nigeria, who in the 1960s resisted neo-colonialism and celebrated the “secret world” of their ancestors. Writing in Fani-Kayode’s 1988 book Black Male / White Male, Hirst notes that “his photographs express the belief that magic, masquerade and erotic delirium are essential elements in challenging the impoverishment of the soul”.

Fani-Kayode worked extensively in the studio and almost exclusively in black and white, emphasising the almost-sculptural curvature of muscles, veins, and skin – Pardo talks of his large, square prints as having the classical quality of Edward Weston or Bill Brandt. In one of his most celebrated images, a bronze head is clenched between the smooth buttocks of a black man – ambiguous whether he’s inserting it or birthing it. While in Techniques of Ecstasy No. 4 a nude man sits, perhaps weeping, over the supine body of another, bringing to mind images of the ancient Greek hero Achilles mourning his comrade and lover Patroclus. “I made my pictures homosexual on purpose,” Fani-Kayode once said. “Black men from the Third World have not previously revealed either to their own peoples or to the West a certain shocking fact: they can desire each other.”

The 1980s saw neo-Nazi street movements spearhead establishment homophobia in the form of the notorious Section 28, which banned the “intentional promotion” of homosexuality, meanwhile HIV/Aids-plagued communities, wiping out a generation. Amid this, Fani-Kayode dedicated himself to helping young, marginalised artists. Barely a year before his death he co-founded and chaired the Association of Black Photographers, which has supported artists since. Fani-Kayode’s commitment was unshakeable: “It is photography, therefore – black, African, homosexual photography – which I must use not just as an instrument, but as a weapon if I am to resist attacks on my integrity and, indeed, my existence on my own terms.”

Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography is at the Barbican Centre, London, until May 17, 2020.