Cutting-edge: A new documentary tells the story of Cuts, the hairdressers frequented by Goldie, Neneh Cherry and Boy George, along with punks, new romantics, Rastas and rockabillies

- TextStuart Brumfitt

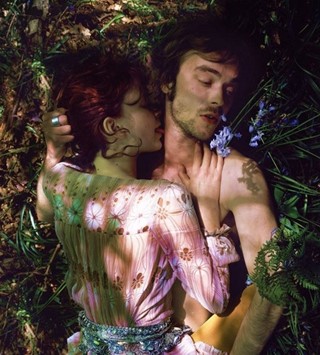

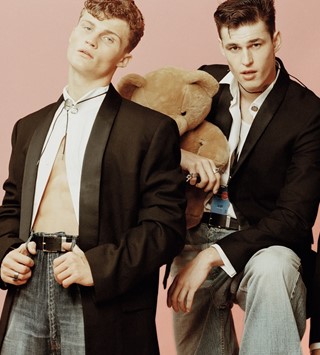

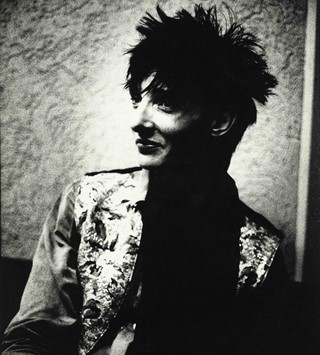

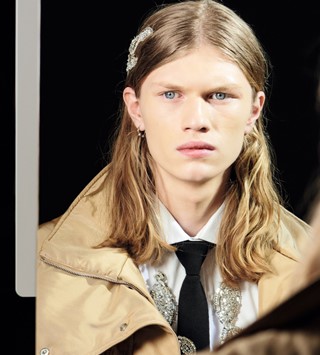

Such was the mad, freewheeling energy of London hair salon Cuts that a “year in the life” documentary about it ended up taking 22 years to make. Now Sarah Lewis’s NO IFS OR BUTS is finally finished and tells the story of a hairdressers that doubled up as a cutting-edge cultural hub frequented by Goldie, Neneh Cherry, Boy George, James Lavelle and Isaac Julien and welcoming punks, new romantics, Rastas and rockabillies.

Started in Kensington Market in 1978 by James Lebon (brother to Mark and uncle to Tyrone), Cuts produced looks that were seen all over i-D and The Face (stylist Ray Petri and his Buffalo movement had a major connection to the salon). The film’s focus though largely falls on the Soho shop, which Lebon opened with business partner Steve Brooks in 1984 and which Brooks carried on with long after Lebon left to pursue a career in high-end hair sessions and pop music promos (sadly passing of a heart attack in 2008). Over nearly 30 years, Brooks endures as the life and soul of the salon, but also its damaged and disruptive daddy figure. “You have heart honey and you have soul,” Neneh Cherry says of him, whilst also joking/worrying that he has a “demented demon” dancing round inside.

Sarah Lewis’s film captures the hedonism, creativity and confidence of a young multicultural scene, but also many of its members’ descents into drug addiction, mental health issues and even suicide. It’s a look at an extended heyday, but also an examination of the price that’s often paid for living life at full throttle. Here, ahead of her film’s premiere at the London BFI Festival on October 20, and alongside a preview of a book about the salon coming out in December, she tells us five things you need to know about Cuts.

It Was a Rare, Racially Diverse Barbershop

“I know that the first time Pete, a white guy, had to cut hair it was a black man’s hair and he was just absolutely crapping himself about not getting it right. There was ‘the armadillo’, the haircut that Goldie had, and I remember Roy [a white hairdresser] getting that slightly wrong once and that was a complete disaster. But yeah, everyone had to adapt because the whole ethos of the place was inclusive. The culture of the place fed into the culture of the hairstyles. It wouldn’t have been authentic if they hadn’t known how to work with different people’s hair. It really pushed the boundaries. Before then, the places where people had their hair cut were really segregated. But there was this ethos of egalitarianism, breaking down boundaries. The people running the place were bringing people together, so it had to follow through that they really understood different hair types and styles and what was cutting edge.”

Although There Was a Questionable Attitude to the Queer Community (James Lebon Says That the First Rule of the Salon Was That They Didn’t Want Any Camp Guys Working There)

“In that time, there was a different language to talk about sexuality. It’s a little bit shocking. The word ‘poof’ [interviewing James Lebon for TV show The Tube, Paula Yates asks, ‘Why do you think that so many people think that hairdressers are poofs?’] – I’ve not heard that for about 20 years. I included that clip because I thought that was quite interesting about how James was really upfront about that. I suppose he was finding a place for himself outside the stereotype of what hairdressing was. And he might have said that, but he was obviously very inclusive, so I think it kind of indicates what kind of character he was too. He wasn’t afraid of expressing his own needs and perspective, even if it might not have been fashionable – and while acting in a different way from what he was saying.”

So in Reality, All Were Welcome

“It was a cultural hub and a way that people could meet and connect in person. I’ve got footage that isn’t in the film of people saying, ‘Oh it’s so intimidating to go in there,’ but actually when they went in there it was completely accepting of all different types of people. You obviously had the fashion types and the trendy types, but there was also room for people who might have been homeless. I did have footage where there was a woman who had just been released from prison and she came in and said, ‘I’ve only got £2. Can you do my hair?’ So there was room for people like that also. Real outsiders used to just come and sit on the bench there. It really offered a space for people that other places didn’t. People’s lives became bigger as a result of being part of that.”

The Drugs Don’t Work

“It was really traumatic with Steve and I knew what an impact it had had on the people in the shop, and I knew the state that he was in. He was completely unravelling with drug addiction and James’s death, and I didn’t know what was going to happen. But he gradually started to rebuild his life. I think addiction and the denial that comes with addiction is problematic. If people are not able to really understand what’s going on with regards to taking drugs, then it can be really disruptive in people’s lives and the lives of the people they love and are connected to.”

Good Things Come to Those Who Wait… For 22 Years

“The nature of Cuts dictated the energy of the process of making the film. I was working on it with Jenny Selden at the start and we were desperate to move it on, but it seemed to have its own rhythm that took a lot longer and was a lot more frustrating than what we’d set out to do. But over 22 years, we got the development of people’s lives. It would have been a very different film [if they’d only filmed for a year]. The film is based in Cuts, but it also talks about how we are, or not, able to connect with people and the vulnerabilities that we have. And that’s expressed through Steve. The vulnerabilities within the context of that trendy world.”

NO IFS OR BUTS premieres at the London BFI Festival on October 20