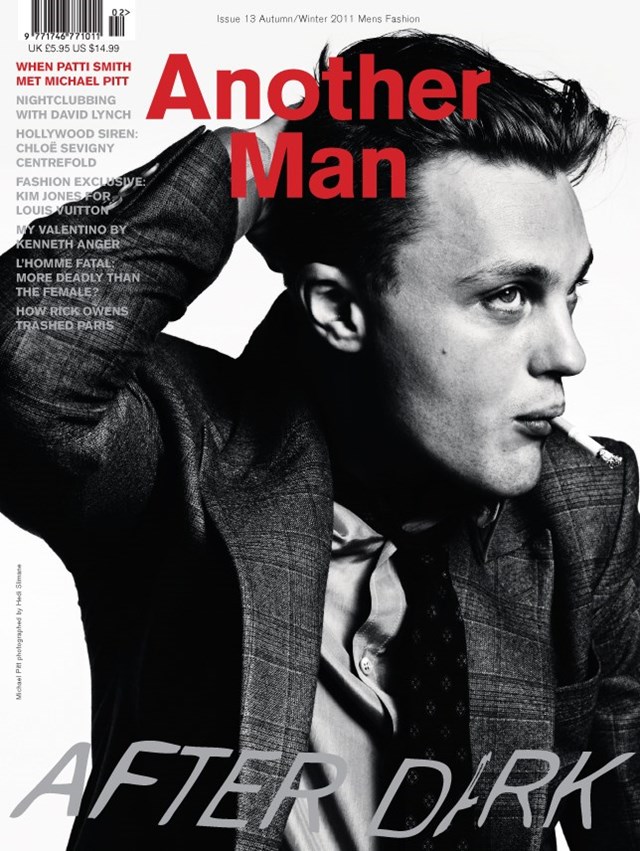

Michael Pitt

Michael Pitt used to be a teen pin-up. One season as heartbreaking quarterback Henry Parker in hit series Dawson’s Creek was all it took. Suddenly 13-year-old girls put up posters of him in their pink bedrooms and swooned over his boyish DiCaprio beauty. They watched him seduce and kiss bad girl Jen on TV, and imagined it was them. They nicknamed him “Pillow Lips”. It made him feel awkward and embarrassed. He was grateful for the money and the work but he wanted to run away. He wanted to do things on his own terms... One year later, he emerged with a silver cross painted on his forehead, transformed into glam rock God Tommy Gnosis for Hedwig and the Angry Inch. He channelled Bowie’s strange, confusing sexuality. He pranced and pouted like Jagger. He suddenly looked dangerous and damaged – a perfect combination. As wide-eyed American student Matthew, he stripped off and jumped into bed with a bohemian brother and sister while the 1968 Paris riots raged outside. He didn’t care that Jake Gyllenhaal – scared of all the full-frontal nudity and fucking in Bertolucci’s The Dreamers– had turned down the role at the last minute; like the character, he went to France in search of experiences, hoping to be corrupted. In Last Days, Gus Van Sant turned him into Kurt Cobain. He was scared of inhabiting that tortured soul but he knew he had to. It lived on in him for a long time. He tried to shake the haunting by playing a homicidal maniac in white golf gloves for an Austrian director remaking his own film Funny Games. It worked. He was ready for his next act. On September 19, 2010 the first episode of HBO’s gangland saga Boardwalk Empire aired. That night he was reborn as mobster protégé Jimmy Darmody. With his slicked back hair, tailored suit and pretty boy looks, he had all the lethal attraction of Helmut Berger – the ultimate homme fatal. Michael Pitt had come of age.

When we first met a few years ago, his golden hair was long and he still carried, if unconsciously, vestiges of his Cobain-like character in Last Days. He appeared at the Abbey of Saint Germain-des-Prés, where I was singing from dusk until dawn with my son and daughter. It was the annual Nuit Blanche, the Paris all-nighter when art, sculpture, installations and music dominate and replace sleep. He came with his warm and supportive companion Jamie Bochert, who somewhat resembles my younger self, and simply joined us. Sitting on the floor to my right he played guitar, and without words we all fell in together. He was easy to work with and his sonic-scapes magnified our performance. We played like buskers through the night, then said goodbye and went our separate ways.

Getting us together again to accomplish this piece was not so easy. It required a scrappier, more determined kind of magic. He was shooting all-nighters in Brooklyn, as Jimmy Darmody for the HBO series Boardwalk Empire. I was recording long stretches in the city at Electric Lady Studios. People think you have a lot of downtime in these type of jobs, but there’s a reason it’s called downtime. You get caught in the atmosphere of the work. You can’t break from the routine, nor dislodge from your own stupor until the call comes for you to do your part. Then you must be ready to step into the light, play the scene, press your face against the wall, improvise the bridge, and catch the groove. You just get caught up in the long mystically tedious process of creation.

So we were two caught up people. We arranged to meet in the studio that Jimi Hendrix built. I had slated Sunday for light work, figuring we would be free to walk around the city, take pictures, and drink coffee and talk. But Saturday night there was a full moon, a meteor shower, and a heaviness in the air that made it impossible to sleep. Then Sunday came with torrential rains. It rained so hard that people in New Jersey were using canoes to get up and down the street.

But Michael appeared anyway. He arrived at Electric Lady with his guitar and backpack bearing gifts: a guitar pedal for the studio, a bottle of Scotch for the band and something for me in an old cigar box. He was trying to shake the residue of shooting Boardwalk Empire until dawn. I was shaking off lyrics that looped in the air like distorted telegrams. But we looked forward to the prospect of leaving it all behind for a few hours and conversing.

They had cut off his hair to play Jimmy Darmody and I wondered if it felt strange being shorn like Joan of Arc. As if he read my mind he said, “Yeah it’s weird, they cut off my hair.” I thought of taking his picture. I had my old Polaroid camera, but it was dark in the studio, not very good for my limited settings and it was raining too hard to shoot outside. So we just hung out for a while in the control room. I had to lay a vocal down for a new song that my bass player Tony Shanahan and I had written. We had been performing in Madrid when Amy Winehouse died. The sorrow we felt for the sad end of this remarkably gifted girl manifested in our performance and we dedicated “Pissing in the River” to her. Those feelings followed us back to New York, and a few days before Michael came, Tony played me a piece of music that seemed to fit a small poem I had written for her. A modest little song as if plucked from the air.

Michael sat in the control room as I laid down a vocal. It’s always a slightly scary moment. But having him there, open and trusting, was inspiring. I sang it a few times and then we went into the live room to do our interview. We sat there for a while, both of us shy at first, awkward, but in a nice way. We weren’t uncomfortable and slowly we found our way of talking with the strange presence of a tape recorder.

The first thing I wanted to ask him was how he felt taking on Last Days. He told me that he knew he was entering territory sacred to Cobain’s friends and fans, and he wrestled with the moral and artistic issues. But in the end, he felt that this territory, the atmosphere and internal world of Cobain, was also sacred to him. And it was sacred to his director Gus Van Sant. So he entered the character of Blake with his eyes open, and they made Last Days. Not a Hollywood movie. Sometimes it would be just them. Michael would help drag equipment into the forest. Surrounded by the shivering pines of Kurt’s mind.

I asked him if he felt Kurt while he was filming. He was silent only for a moment, as if to gather words that were not too presumptuous, too self-appreciating, and simply said, “There was not a time when I didn’t feel him. He was always there.” Sometimes he felt Kurt observing from a distance, peering through the branches like a ray of sunlight.

I felt I knew just a little of what he spoke, because in that same studio, where we were sitting, my band had recorded “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. I too was treading on sacred ground, messing with an anthem of a generation that could have been my own children’s. But as a performer I understood the suffering of that song. That fame and humiliation seem to go hand in hand. And I felt his presence as well.

Michael told me a story about when Kurt died. He was just a young kid then, but he loved him. He was hanging out with some rappers when the news came on the radio, and he was amazed at their reaction. They were deeply moved, truly saddened, and showed their respect. This made an impression on him, how Kurt crossed over and permeated these hardcore hearts.

I tried to picture Michael as a kid. When he was 13 he slipped away from his home in North Jersey and bummed around New York. By 14 he was sleeping beneath the boardwalk in Coney Island. He finally broke free, booted out of the house at 15 years old, and the bad cherub came to New York City without a penny. He got a job as a bike messenger. No one likes bike messengers. Cars plow into them and pedestrians curse them. If they forget to lock up the bike because of some urgent delivery, someone cops the bike. He lived and slept on the streets, not the first time nor would it be the last time in his life. But you know, sometimes the streets seem a definite upgrade.

We veered off and talked about work. He has the Blakean spirit, magnifying the creative impulse. He writes, draws, acts, and is recording an album. A worker. He doesn’t consider himself an actor per se; he acts when that’s his task at hand. Music is also important to him, but his dream is to direct. To him it encompasses everything: the visual experience, music and language. I asked if he would direct himself. “No. No,” he said quietly, but emphatically.

I shot a glance at him. Michael is at that mystical age of 30, still boyish, yet deeply weathered by experience. As his life contests, he is part cherub, part thug, with the face of an angel and the neck of a young boxer – unconsciously beautiful. Some men are like that. Johnny Depp is like that, totally irreverent about his looks. He beguiles you from his inner self.

Sitting there amongst the recording equipment he seemed just another guitar bum. Yet before the camera he becomes Jimmy Darmody the dangerous angel – stoic, soft spoken and menacing. The lame soldier who rises through the gangster ranks shoulder to shoulder with Al Capone. I asked him if he researched for his part of Jimmy. He devoured the period, finding in the 20s a parallel to the 60s in terms of social upheaval and dramatic political and cultural change. How much of Michael Pitt did he put into the role? “All of me and none of me,” he answered.

We talked awhile about fame. We agreed that it can be risky to get too much too soon. “I slowed things down for myself,” he said. “If I didn’t I’d be dead.” The spirits of the young dead were around us. Jimi, Kurt, Amy. But we switched over to life and its possibilities, the realm of the imagination as it merges with action.

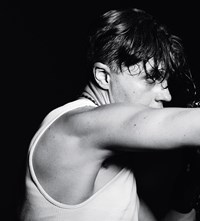

He was hungry so he darted across the street to Grey’s Papaya and bought two hotdogs. I got my camera ready. I was confident I could get a good picture of him but light was scarce. I knew the shot I wanted. There was some artificial light behind my vocal booth that lit up one of the space murals that Hendrix commissioned in 1969 to adorn the studio in which he was hoping to revolutionise music.

A photographer friend Steven Sebring stopped by. He came in from the rain with his own camera, and the last of his precious Polaroid stash. It was like having another kid on the playground that seemed cool. Michael had a digital camera. We all had cameras and bad light. I was using expired Polaroid film in a Land 250 with a collapsing bellow. He said I could use his camera but I don’t have a steady hand. So I set up the shot and Steven took the interior picture with a long exposure.

Then we went into the control room to see what Tony and the engineers were doing. We had a lull and Tony asked to hear Michael’s music. He had entrusted me with a CD, unreleased, unmixed, and still raw. He and Tony talked about speakers and we sat around to listen, not knowing what to expect. It was like a trip into the vortex. Psychedelic rap poetry drum circle. “It’s like the track has eaten mushrooms,” I said, and he laughed. It was nice to see him laugh. He spent time speaking the language of chord changes and frequencies with Tony and the engineer.

I had to leave as I suddenly realised it was feeding time at the zoo. It was still raining but we ventured to my place to feed the cats. I cleaned the litter box and he looked at my books. He picked up my old 1946 Martin guitar, made the year of my birth, and played for a time. I had another camera sitting on the piano with one shot left, so I just snapped him and left it on the piano bench unopened.

We went back to the studio. The rain was letting up. Michael smoked a cigarette and I took a couple pictures of him in front of Electric Lady. We just hung out. Tony was backing up our last track in the control room. We sat around talking about nothing. No tape running, just life. And, after a time, we left the studio. The rain was down to mist. The night was like silver, and we went our own way.

When I later asked Tony to send me the tape so we could transcribe it, he told me we never recorded anything. Michael and I had left it on pause. I remembered the red light flashing, but it was a warning, not a recording. There was 14 minutes that Tony taped of the guys rapping about technology, but that was it. I prowled around thinking about what to do. Michael was back on the set in Brooklyn and I had a heavy night ahead tracking our title song.

“What shall we do?” he asked.

“I don’t know, let me think.”

He had asked me three questions and recorded the answers on his phone.

“I have that,” he said.

The next morning I noticed the Polaroid on the bench and I opened it – Michael playing guitar with the cat zooming past. Somehow it seemed like an encouraging sign. I went to my favourite café and happily it was empty. I sat there for a couple of hours drinking coffee and wrote down everything I could remember. Then I headed to the studio. Back at Electric Lady I called him on the set. I was standing in front of the psychedelic space mural lining the hall where I have stood so many times since recording Horses in 1975. We found a few minutes to talk on the phone. I wanted to ask him just one more thing. The connection wasn’t great, but I could hear him through the crackling, like a voice seeping from an old gramophone record.

“Can you tell me a story about when you were a boy?”

He thought for a moment and then told me this: His father had an auto repair shop in New Jersey. In the summers he would hang out in the adjacent junkyard, a sort of graveyard for expired cars. He would spend his days making sculptures with spare parts, but his creativity was not appreciated. It just got him into trouble, as his dad said he was damaging engines and parts needed for repairs. He was alone most of the days and befriended a dog named Satan. A mangy Doberman that lived outdoors and roamed the work area, often getting sprayed with paint, covered in spots. Satan the dog became his friend and they spent the summer exploring, having adventures, and falling asleep together on summer afternoons. He was too young to know what the word Satan meant. He knew about the devil, but didn’t know his name. And Satan was his friend and he loved him.

That purity has remained within him, through anything he has experienced. It’s what will ultimately sustain him as an artist and a human being. I didn’t tape what he said on the phone but I remembered every word. And ultimately I realised that the most important thing that went down was never on tape anyway. We had become friends. A North Jersey boy and a South Jersey girl. And the best picture I got of him was not with a camera. It came from a memory, when he slept peacefully with Satan in the back seat of an abandoned car beneath the anvil of the sun.