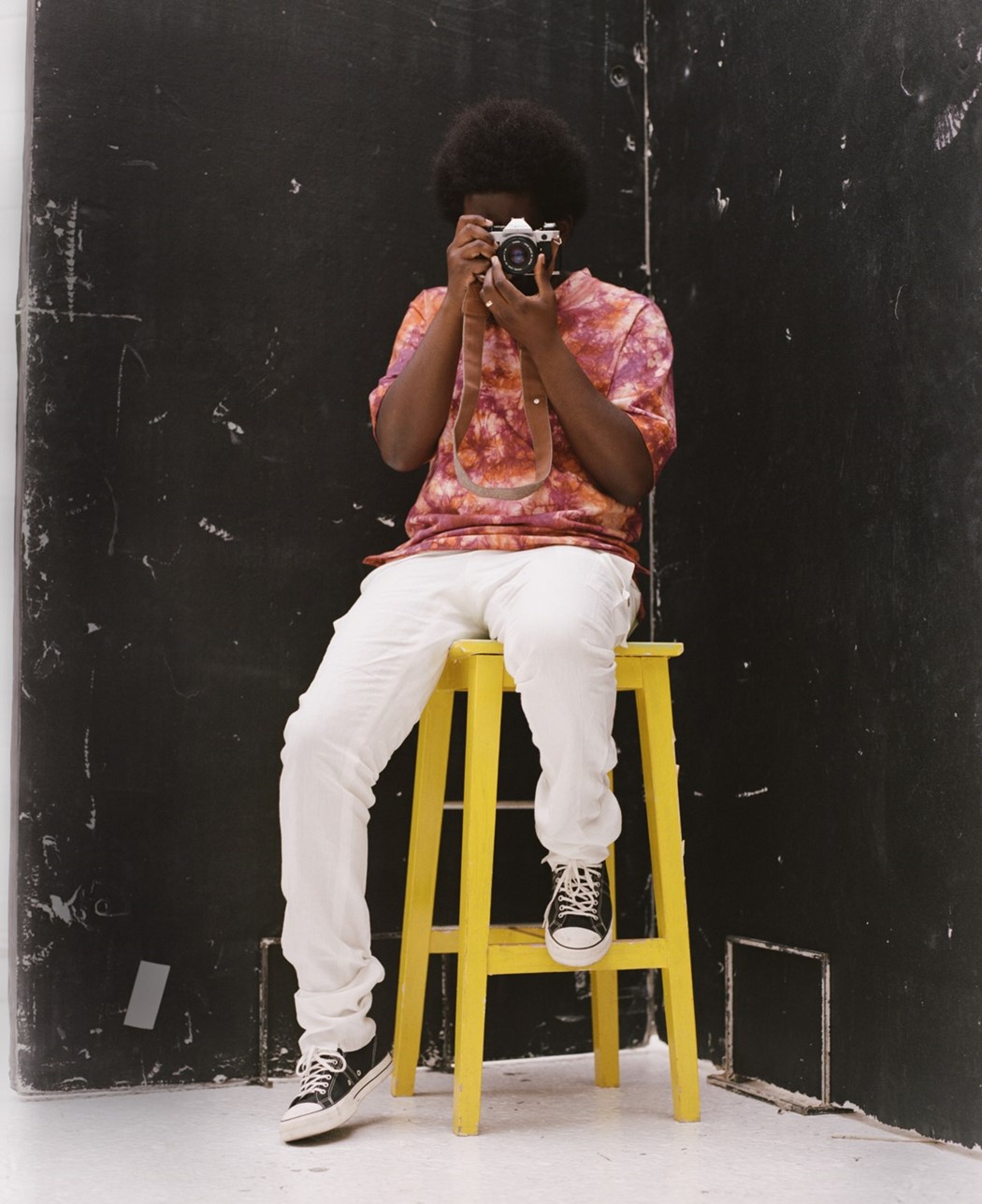

Michael Kiwanuka’s Music is Medicine for the Soul

- TextPaul Moody

The softly spoken singer opens up to Paul Moody about the 70s, self-expression and his self-titled new album, which comes out tomorrow

“I remember seeing Jimi Hendrix on a TV documentary when I was 12,” says Michael Kiwanuka, sitting in the front room of his house in Southampton. “It was from the Isle of Wight festival in 1970, and he was playing The Star-Spangled Banner on a white guitar. I’d never seen a black person with an afro on TV before. I thought to myself: ‘Maybe I’m not so weird after all.’” 20 years on, the singer’s own unique style is inspiring a new generation of musicians to follow their instincts.

Thoughtful and softly spoken, he’s a throwback to more meditative times, as happy enthusing about the opportunities for crate-digging (most recent purchase: Marvin Gaye’s posthumous You’re The Man) and thrift store shopping while on tour in America (“Atlanta is amazing for thrifting, I got a great 70s Wrangler zip-up jacket with corduroy collars there”) as singing his own praises.

Raised in Muswell Hill in a household almost devoid of music – the family record player remained broken for years – Kiwanuka, the son of two escapees from Idi Amin’s Uganda, learned to trust his own musical compass from an early age. A teenage Nirvana fan (“I still think Kurt Cobain is an amazing songwriter”), he found a deeper connection with American soul artists such as Bill Withers, Curtis Mayfield and Roberta Flack, whose music indirectly referenced his own African heritage.

“I know it sounds strange, because culturally there were lots of bad things going on, but I feel like in some ways the 70s was a less inhibited time,” he says. “Things didn’t feel as segregated as they are now in terms of music and fashion. Black people were playing guitars, bass, drums and keyboards, so there were lots of connections to rock and roll, which I love. At the same time, Malcolm X was looking cool in his Ray-Bans and the Black Panthers were wearing their hair out to express their African identity and wearing leather jackets. Everything linked together in a new form of self-expression. It wasn’t just about Nikes and sportswear.”

In an era when pop is so artfully manufactured, it’s sometimes impossible to tell the genuine from the fake, it’s this heightened sense of aesthetics which marks Kiwanuka out as the real deal. Having cut his teeth as a session guitarist for the likes of Chipmunk, he’s built a following the old-fashioned way, touring globally in support of Mercury-nominated 2012 debut Home Again and chart-topping 2016 follow-up Love & Hate, while gaining cultural traction through his music being featured on – among others – Baz Luhrmann’s Netflix series The Get Down, about the beginnings of hip-hop in New York, and HBO’s Emmy-winning Big Little Lies.

Recorded between New York, London and LA with Brian ‘Dangermouse’ Burton (Gnarls Barkley) and hip-hop producer Inflo, his self-titled third album seems set to reach an even wider audience. Musically, it mines the past with expert precision, combining nods to everyone from Shuggie Otis (future smash hit Rolling) to Fela Kuti (an Afrobeat-inspired Final Days) to Bobby Womack (You Ain’t The Problem). The lyrics, meanwhile, explore contemporary issues through the prism of the past. Another Human Being features a quote taken from a participant in the Civil Rights sit-in protests that swept through North Carolina in 1960, while Hero is a tribute to Chicago Black Panther leader Fred Hampton.

The title, he explains, is a reflection of the fact that, at 32, he is finally beginning to feel comfortable in the spotlight. “It’s taken me a while, because I’ve always had a tendency to overthink things,” he says with a grin. “I’ve learned not to be so hard on myself. If sometimes things don’t work out, it doesn’t necessarily mean you should blame yourself – it just wasn’t the right time. People start changing because they feel they need to fit in. But I don’t think that’s the healthiest way to approach life. You have to be true to yourself, and you need to stand up for yourself. You get the most out of life when you’re living who you really are.”

Ultimately, Kiwanuka is a record which finds him both celebrating his African roots while preaching a message of unification – of soul, spirit and mind. It’s a message brought together in the album’s centrepiece, the spellbinding Piano Joint (This Kind Of Love), inspired by the spiritual jazz-gospel of Alice Coltrane.

“All the tracks flow into each other, and my idea was to try and allow people to lose themselves in the music,” he says. “I wanted it to have the same effect as when you go to a gallery or an exhibition or watch an amazing film, when you’re transported somewhere else. When you experience something like that it makes you feel alive, and it fills you up with good energy. For me, that’s the prime purpose of art – to make you feel like a human being, and help you tackle the day.”

In troubled times, when depressing headlines are always just a click away, Michael Kiwanuka’s music remains medicine for the soul.

KIWANUKA is out November 1, 2019.