Miss Rosen charts the rise and fall – and rise again – of the late photographer Mel Roberts, who captured young men on the beaches of California

- TextMiss Rosen

Tales from another time... In a new series, titled Illicit Histories, Miss Rosen tells the stories of queer art’s pioneers, unpacking the lives and work of people who revolutionised gay erotic imagery – often in defiance of censorship laws.

Photographer and filmmaker Mel Roberts (1923–2007) lived and worked as an openly gay man at a time when it was illegal to do so. Hailing from Toledo, Ohio, Roberts started shooting 16mm films of his friend as a teen before being drafted in 1943, where he served as a cameraman documenting World War II in the South Pacific.

Like so many gay men of the era, he migrated to California after the war, drawn to the heady mix of freedom of expression and career opportunities. After getting his degree in filmmaking from the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, Roberts worked as a film editor and soon discovered Physique Pictorial magazine at a newsstand near the studio.

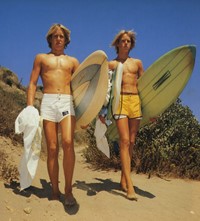

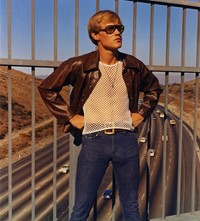

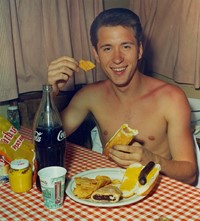

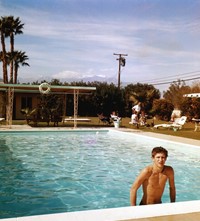

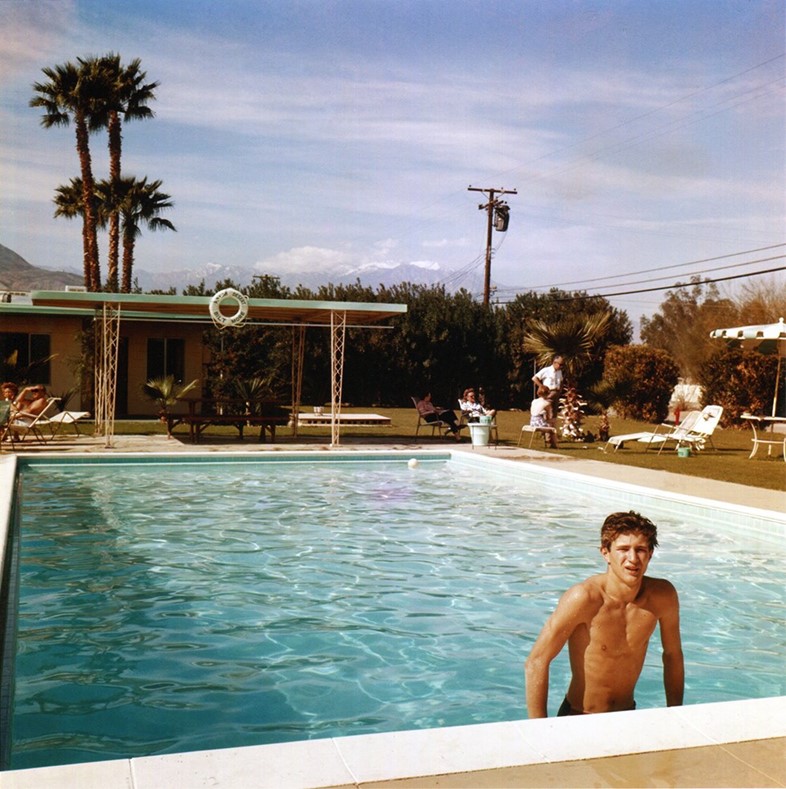

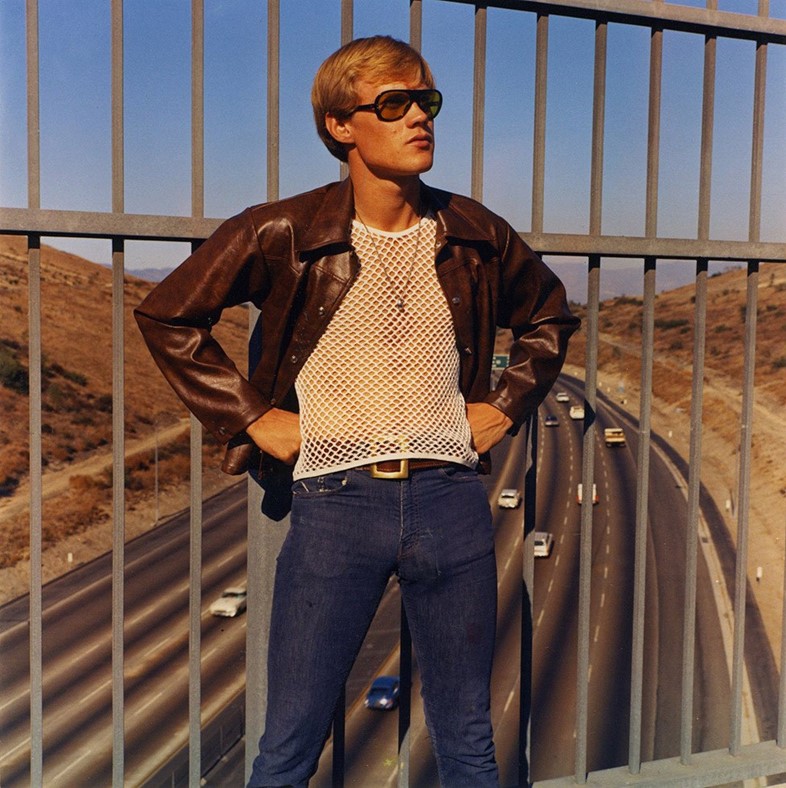

Inspiration struck and Roberts set forth to create a portrait of fun in the sun, California style. From the 1950s until 1981, he amassed an archive of 50,000 photographs of almost 200 male models. Eschewing the classic bodybuilder archetype popularised by Bruce of Los Angeles and Bob Mizer, Roberts preferred the boy-next-door aesthetic. He began publishing his work in Young Physique magazine in 1963, offering light and fun pictures made on day trips to picturesque towns like Yosemite, Idlewild, and La Jolla.

“There is a narrative aspect to his work that you could attribute to storytelling and moving film,” says Brian Paul Clamp, gallerist, who represented Roberts in the final years of his life. Each image has a simple scenario: the biker pausing en route, hitchhikers on the side of the road, a quick dip in the pool, and surfers on the dunes. Many of the models became lovers, others became friends, some became roommates, while others simply came and went.

“He didn’t have any hang ups about being an openly gay man,” Clamp says. “At the same time, he was cautious and understood some of the dangers of being out.”

While working for a large aircraft manufacturer in San Diego, Roberts was fired without cause. He told Clamp, “I was right in the middle of directing a film when I went to the office and was told to leave the building immediately. I couldn’t figure out why. They never told me. I didn’t pass the security clearance, obviously. I assumed there were two reasons: I had worked on [the blacklisted film] Salt of the Earth and because I was gay.”

Working the McCarthy Era, Roberts understood the dangers of government persecution. Shortly after graduating from USC, he took a job as music editor on Salt of the Earth, a 1954 Neorealist film about Mexican-American miners fighting for decent working conditions. Deemed subversive, the film was blacklisted over alleged ties to Communism. This did not stop Roberts from uniting with activists.

He joined the Mattachine Society, one of the earliest gay rights organisations in the United States, which was founded by Harry Hay in 1950 and headquartered in Los Angeles. Many of the founders were Communist and adopted a similar structure to the group, organising cells, oaths of secrecy, and different levels of membership. The group sought to unify the LGBTQ community, and educate its members of their rights, which were frequently trampled by the police and employers.

Knowing he could be sent to prison for full frontal male nudity, Roberts built his own colour lab at home to develop his photographs – after Eastman Kodak returned his transparencies with holes punched through where the genitals would otherwise be. For decades, Roberts was able to live on his own terms. Then, in 1977, the Los Angeles Police Department raided his Bel Air home, seizing all of his negatives, prints, cameras, and mailing lists.

“The police assumed some of his models were under 18 but Roberts had full proof all his models were of age. Everything was above board,” Clamp says. “The police were never able to find anything illegal and he was never charged with any crimes. He had to spend a great amount of time and money trying to get back what was rightfully his; when he would receive things back, things would be missing or damaged.”

Two years later, the LAPD raided his home again. No charges were filed but the damage had been done. Roberts was effectively forced to retire in 1981. That didn’t stop the LAPD from returning once more in 1992, failing once again to find any evidence of criminal activity.

Soon thereafter, photographer Rick Castro discovered Roberts showing his photographs in the back room of a video store in North Hollywood and organised Homosexual Overkill, a 1996 group exhibition at Rita Dean Gallery in San Diego that lead to Roberts getting a book deal from FotoFactory Press. In 2000, California Boys: Photographs from the 1980s and 1970s was published, and the following year The Wild Ones: The Erotic Photography of Mel Roberts was released – both of which have since become collector’s items.

Then, in 2003, Clamp featured Roberts in the group show Boys of Summer and made his most famous photograph, Indio, the poster for the exhibition. “He was a funny, humble guy,” Clamp says. “He was still hurt and angered by the harassment he received from the LAPD but he had moved beyond that and really appreciated the attention he was getting for his work.”