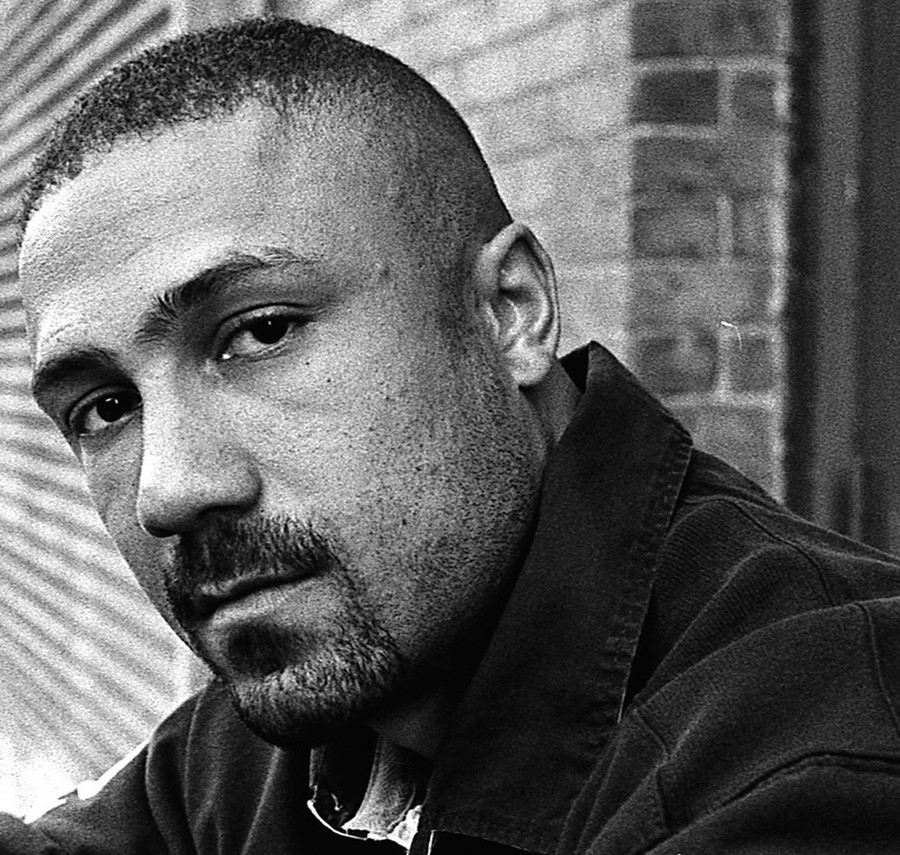

The Man Behind Black Mother, an Epic New Film About Jamaican Identity

- TextStuart Brumfitt

Khalik Allah is one of the most important and original filmmakers working today. As his latest feature hits cinemas, he opens up about his job, ‘the Beyoncé thing’ and his favourite films – plus, he shares some advice to artists

Background: Khalik Allah grew up in Suffolk, Long Island, New York, but moved between Queens and Harlem throughout his childhood. He has a Jamaican mother and an Iranian father who met when they were at university in Bristol in the UK. He has spent much of his life visiting Jamaica, but is yet to make it to Iran. He recently got himself Jamaican citizenship because of Trump’s election. “Once that happened, I said, ‘I want to get the fuck out of here.’ I need to at least have a little exit strategy.”

Job: He rose to prominence with his film Popa Wu: A 5% Story, his photography book Souls Against The Concrete and his documentary Field Niggas and a contribution to Beyoncé’s Lemonade (more on that later). His new release, Black Mother, out now, is a heady, hallucinatory study of Jamaica that looks at the “marriage between the profane and the sacred.” It’s not about motherhood, but his motherland. “Jamaica itself is the black mother to me. The first trimester of my film – as my film was broken into three trimesters – deals with the land, the food, the water. All of that represents the mother to me. The whole film is a unique perspective on Jamaica, because I’ve never seen a film about Jamaica that wasn’t about reggae, dance, or something to do with like marijuana. This film goes way beneath the surface.”

He’s Bigger Than His Beyoncé Contribution: “When I do interviews, people always bring up the Beyoncé thing, and that’s fine – I’m proud that I was able to work on that – but Black Mother was already in motion long before I started doing that thing. The funding of that film was going on long before I started doing that as well.”

He’s a Five Percenter: “The Five-Percent Nation was grown out of people that were street delinquent, young kids between the ages of eight and 16. Now a lot of those brothers are older, we call them the ‘older gods.’ I’m still active.” To Five-Percenters, Harlem is Mecca and Brooklyn is Medina. “Basically the Five-Percent Nation started when Clarence Smith, or Clarence 13X, was in the Nation of Islam under the leadership of Malcolm X, and he left the temple and started teaching that the black man is god. He took that to the streets. It was called ‘supreme wisdom’, with these 120 lessons, which you memorise and learn how to quote. He gave that wisdom to the children that were gang members, so it really helped give these young men direction. School ruins people’s appetite for knowledge. You don’t want to read anything after reading these books that they gave you. You’re just kind of like ‘Fuck a book’, but after being sparked, I was like ‘Wow, education is actually cool, it’s cool to read.’ That’s what the Five-Percent Nation did for me.”

He’s a Film Buff: He loves “old bible style movies” like Spartacus and Demetrius and the Gladiators. Also, “Hitchcock, stuff from the 70s and old epics.” Larry Clarke’s Kids, Kim Ki-duk’s Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring, and Hype Williams’ Belly are some of his favourites too.

He Loves His Cameras: His first camera was a Hi8 Canon, ES190, which his mum bought for him. For Black Mother, he used six different cameras to give different effects. “I used the Super 8 camera, a 16mm camera, the Bolex, a Lumix, the drone, the ES190 Canon and then a mini DV camera.” If he could just use one camera though, it would be the Bolex. “There’s a certain spirituality and nostalgia that I feel that the Bolex facilitates. And shooting it with a 10mm lens gives you that nice wide-angle effect. I also was alternating between the 10mm and the 50mm, which is more focused and narrow, because the whole film is mostly portraits. I’m a photographer, this is a photographer’s documentary.” He says he loves studying the different functions of cameras. “When I’m learning about cameras, I’m learning about how I could flip it. Maybe you’re meant to do this type of thing, but maybe artistically I could turn it upside-down and do something that’s unexpected and it give me a different effect. That’s why I love the technical side.”

His Advice to Artists: Allah decided he didn’t want to have to shoot weddings and bar mitzvahs, instead choosing to work in nursing homes and as a broadcasting technician for TV channels. “I always wanted to keep the camera separate from money, so I had a job to prevent me from doing film work just to make money. I wanted to keep the camera pure. He encourages artists to “keep your passions and things that you need to do just to survive separate, because you don’t want anything to corrupt something that means so much to you.” He also encourages artists not to hold their work back: “Put it out there and share it, because people will see it and they’ll start to share your vision and believe in your vision and might want to get behind it.”

Next Up: He’s ready to move away from documentary and into fiction narrative features. “I want to write a script. I don’t want to stay in my comfort zone. It would be easy to continue with this style of documentary, which gave me success and brought me all over the world, but I look at it just as a stepping stone to get to the next dimension of my own career.” He sees his career as something akin to writing a Qur’an or a Bible. “I’m 33 now and by the time I get to 73, I want to feel like, ‘I touched so many people through my work.’ To me it’s more than photography, it’s more than filmmaking, it’s actually about touching people and affecting people on a spiritual level. That’s my purpose here – like a minister, man. Film is just an excuse, photography is just an excuse for me to affect people in a spiritual way.”

Black Mother is out now