Miss Rosen speaks to Hunter Reynolds as he prepares to stage a new exhibition titled Drag to Dervish, which celebrates and chronicles the life of Patina du Prey

- TextMiss Rosen

After receiving his BFA from Otis-Parsons Art Institute in Los Angeles in 1984, Hunter Reynolds moved across the country to New York’s East Village. He settled into new digs on Eighth Street, sharing a flat with Aldo Hernandez, a DJ at the Pyramid Club and a fixture on the downtown underground scene that catapulted a new generation of politically-conscious drag performers like RuPaul, Lady Bunny, and Lypsinka into the spotlight.

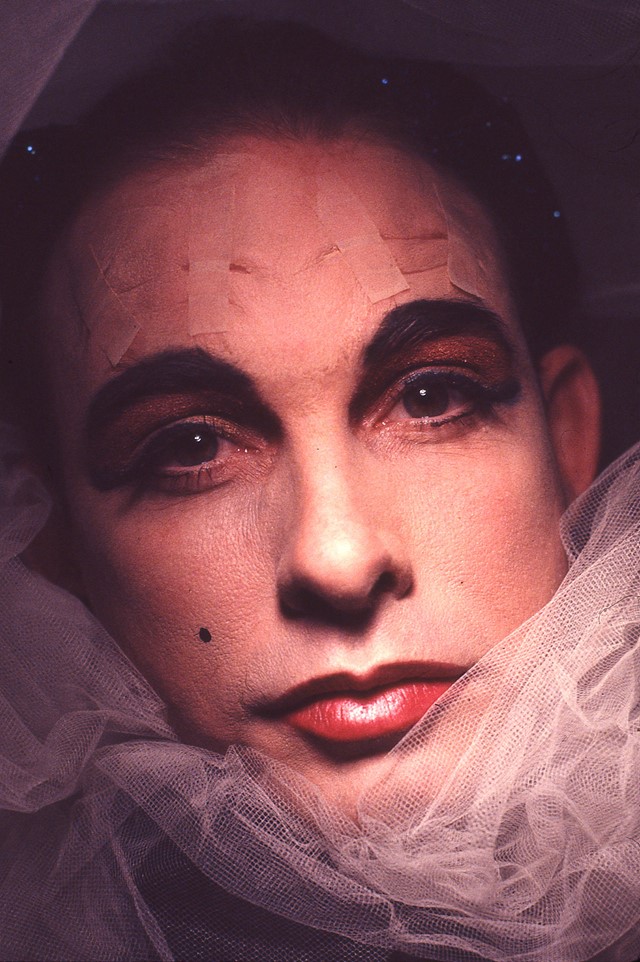

Inspired by their radical aesthetics, Reynolds instinctively knew that he wanted to take drag out of this context and explore it in his own way. “I started by removing my beard and putting make up on to transform into a feminine look. But not totally drag. I wanted to show my chest hair – [the] third gender is what I called it,” Reynolds tells Another Man on a break from installing Drag to Dervish, a retrospective exhibition chronicling the life of his alter ego, Patina du Prey.

Reynolds’ journey into gender-bending began in 1989 when he partnered with photographer Michael Wakefield for a private performance documenting the transformation process on film. “Three days later I got the pictures back and realised, ‘Oh my God!’” Reynolds remembers. “I confronted myself with my own identity. I threw them into a drawer and didn’t look at them for several months.”

But Patina was destined for the public eye. After a dealer offered to exhibit the work, Reynolds became emboldened to drag up and go out for a night on the town, to a performance at the Kitchen accompanied by Hernandez, then an opening at Leo Castelli Gallery. At first no one recognised him; then word got out. “That was the birth of Patina,” Reynolds says.

It was also the same year Reynolds found out that he was HIV positive. While in college, Reynolds participated in a UCLA study that had begun in the 1970s tracking the lives of gay men. “They had my blood work from 1982 to 1987 but I never asked for the results because I didn’t want to know,” Reynolds says. “I found out in 1989 that I had been positive since 1984.”

By that time, Reynolds had been a member of ACT UP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) for two years. His participation in the grassroots activist group gave him the courage, confidence and strength to launch Art Positive, an affinity group, in response to Mark Kostabi’s incendiary statement made in a 1989 Vanity Fair profile.

Kostabi was quotes as saying, “These museum curators, that are for the most part homosexual, have controlled the art world in the 80s. Now they’re all dying of Aids, and although I think it’s sad, I know it’s for the better. Because homosexual men are not actively participating in the perpetuation of human life.”

“I knew him and I lost it,” Reynolds says. “I had to do something so I got my voice together, stood up in front of the meeting for the first time, and created an action against him. 60 people showed up.”

Art Positive stayed together for the next four years, operating after Reynolds decamped to Berlin in 1992 for an artist residency. “It went on without me. I didn’t expect to be alive,” Reynolds says. “A friend of mine who died gave me his deathbed wisdom to not let this thing control my body – to take control of it. He said, ‘Just make your art.’ I got that and went with it. It ended up taking me through the years that this show is about.”

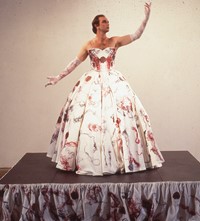

Drag to Dervish traces Reynolds’ intuitive path as Patina du Prey, focusing on the transformative power of art as a tool for catharsis, healing, and activism. Combining fashion, beauty, and dance, Reynolds became the canvas for a series of performances, guerilla actions, and collaborative projects that took on issues of systemic oppression and internalised phobias by harnessing the transcendent power of beauty.

Whether sitting inside an art gallery and undergoing the ritual transformation for Drag Pose Cage (1990) or dancing in a Dervish Dress for I-DEA: The Goddess Within (1993–2000), Reynolds’ work has a striking effect on the audience. In Europe, people treated him as a forest fairy, recognising a connection to their mythology. Whereas in Los Angeles, on Hollywood Boulevard, someone pulled a machete and threatened Reynolds. “My motto was ‘Keep moving!’” he says, laughing off the spectre of death once again.

But it is perhaps The Memorial Dress (1993–1997) that has had the most profound effect, a project that began during Reynolds’ Berlin residency. After seeing the NAMES Project Aids Memorial Quilt displayed on the Washington Mall in 1992, Reynolds decided to make a black silk ballgown bearing the names of the 25,000 people lost to AIDS.

When the dress was unveiled in the 1993 Dress Codes show at the ICA in Boston, Reynolds reveals, “I wasn’t prepared for the intensity of it. People found the names of their friends on the dress and began crying, having cathartic events in front of me. I did six weeks of performances almost daily and it changed the direction of my work, connecting to the body and spirit, with the dress as a spiritual vortex to the universe.”

With this new understanding of his work, people came into Reynolds’ life to guide him along the path. He began studying Sufi Dervish dancing in Berlin, stepping off the stage in his underskirt, and spinning in a trance-like state. Together, with photographer Maxine Henderson, they created I-DEA: The Goddess Within, a series of performances over a period of eight years, documented in more than 13,000 images.

In the whirlwind, Patina du Prey continued to evolve and ultimately ascend into another realm, disappearing after Reynolds returned to New York and 9/11 happened. But in Drag to Dervish, her spirit emerges once again, perhaps at a time when Reynolds needs her more than ever.

“Living as a long term survivor has been very difficult. I have had everything – HIV strokes. It doesn’t end. I have a lot of medical stuff going on right now that can bring you down,” Reynolds reveals. But as he installs the exhibition, Patina’s spirit re-emerges as a guiding light, allowing Reynolds to see her full glory brought together for the first time in his life.

“I was always trying to use my work to heal myself,” he says. “Sometimes I lose myself and my work is what brings me back.”

Drag to Dervish is on view at P.P.O.W. Gallery in New York until December 21, 2019.