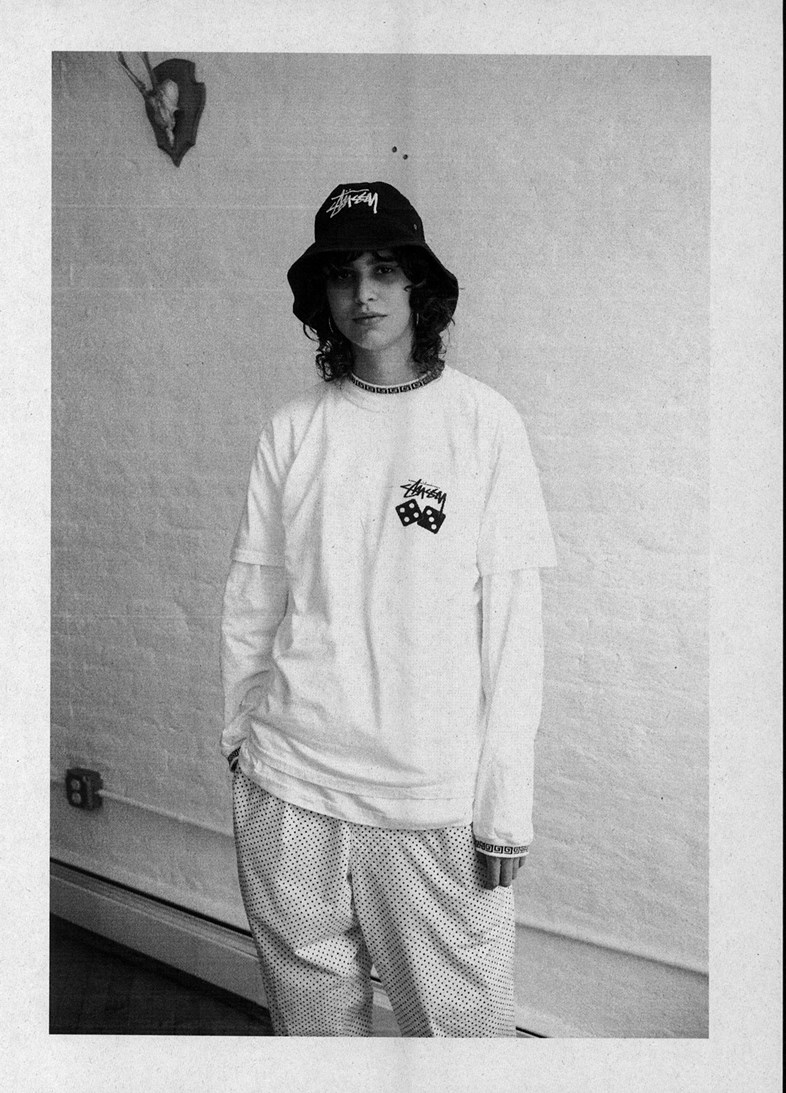

We preview a new book about the revolutionary brand and explore its influence on fashion, and why it was so ahead of its time

- TextCalum Gordon

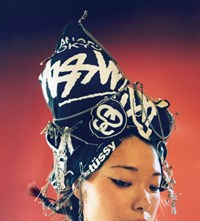

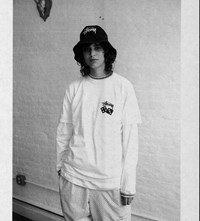

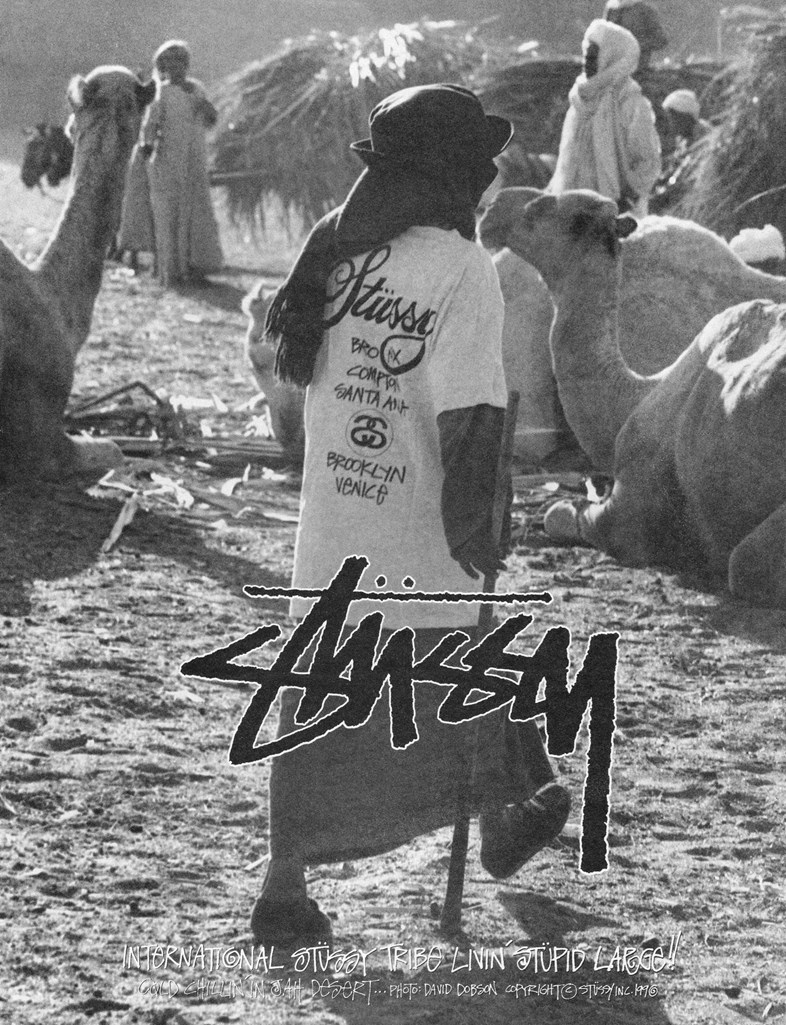

When looking at pictures of Stüssy t-shirts and campaigns, it’s often hard to distinguish what’s from the past and what’s current. The handwriting is the same, literally. In Shawn Stüssy’s inimitable scrawl, the brand has a rich visual language, one that feels slightly nostalgic – created long before the days of Photoshop, but still relevant.

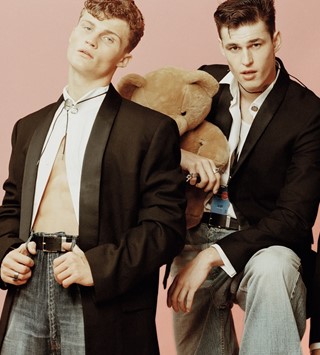

That relevancy is explored in Stüssy’s latest book, released in collaboration with London publishing house IDEA, which looks at the Californian brand’s t-shirts, spanning from the early 80s up until present day. Under the guidance of stylist Alastair McKimm and Ryan Willms (the founder and former Editor-in-Chief of Inventory magazine who works with Stüssy on special projects), it does an excellent job of further blurring the lines between old and new, as old yellowed t-shirts are shot by contemporary photographers such as Alasdair McLellan, as if to hammer home the point that it doesn’t really matter. What matters is that Stüssy remains as intriguing and exciting as it ever was. But how did it get here; from hawking hand-shaped surfboards by the beach to becoming one of the most influential fashion brands in existence?

While Shawn Stüssy started out making surfboards – and still does to this day, having exited his eponymous brand in 1996 – it was ultimately his t-shirts that thrust his work into the spotlight. It was a time where there were few ways of identifying yourself as being different, according to Chris Gibbs, owner of Los Angeles streetwear store Union (which also once shared a retail space with Stüssy’s): “Before street wear (sic) you often would wear something from your favourite team or band or sports brand. Or take it step further a lot of kids would wear clothing from brands that didn’t represent them at all,” Gibbs said. Stüssy – arguably the first of its ilk – was the antidote to that, deftly blending skate and surf, hip-hop, punk and club culture. It came about as a combination of Stüssy’s inherent fascination with underground subcultures, and a happy accident – he first printed t-shirts with his iconic writing style as a promotional tool to help sell his surfboards.

“Stüssy – arguably the first of its ilk – was the antidote to that, deftly blending skate and surf, hip-hop, punk and club culture”

While the brand was not an overnight success, by the end of the 80s it had come to be adopted on both coasts of the US, with knowing nods being exchanged between strangers wearing one of the brand’s pieces. The curatorial aspect to Stüssy’s designs was key, often using t-shirts as a canvas to deliver an eclectic mix of graphics and counter-cultural cues. That in itself was a radical act – at that point, no brand had ever considered appealing to the otherness of teenagers. Now, it accounts for a whole sub-genre of fashion design, seeping into the work of everyone from Raf Simons to Neek Lurk of cult internet brand Anti Social Social Club. (Lurk also works for Stüssy, maintaining a job at the company despite the meteoric rise of his label).

But arguably Stüssy’s most powerful and lasting act came in its decision to begin subverting the logos of other brands. When, in the middle of that 80s, Stüssy created an interlocking ‘S’ emblem in homage to Chanel, it inadvertently spawned a whole new mode of t-shirt design. It might not have been the first to riff on the iconography of other brands, but it certainly pushed the idea into the consciousness of the fashion mainstream. Without it, there would be no DHL by Vetements, no Gosha-does-Hilfiger, and no Palace spin on the Versace Medusa head.

“Without [Stüssy], there would be no DHL by Vetements, no Gosha-does-Hilfiger, and no Palace spin on the Versace Medusa head”

It was not simply Shawn Stüssy’s visionary design outlook which endures today, the brand – under the guidance of its founder – also pre-empted “influencer marketing”. Except, rather than #sponsored #ad bloggers, he created a global network of friends and confidants – a mixture of DJs, club kids and sharp dressers – who would ultimately spread the word about Stüssy in their respective cities of Tokyo, New York and London. This loose group of affiliates was dubbed the International Stüssy Tribe (IST) and, like Stüssy’s Chanel-homage, continues to influence fashion to this day. Arguably one of the biggest talking points in fashion of the last year, the Louis Vuitton x Supreme collaboration, can be traced back to Michael Koppelman, owner of London’s Gimme5 and an original IST member. Not only did he help establish Stüssy in the UK, he did the same for Supreme, as well as giving a start in fashion to a young designer by the name of Kim Jones. Hiroshi Fujiwara, another original recent collaborator of Jones’ at Louis Vuitton was another key Tribe member.

“I think that Stüssy was definitely a pioneer in creating a community with subcultures around the world,” says Willms when asked about the unique nature of the International Stüssy Tribe. “I met Lono Brazil in Paris two years ago, he’s a 50 year old music producer and model and he threw the original Stüssy party in Tokyo. Through that connection I’ve got to hang out with him, photograph him for other jobs, listened to his music and learnt about Chicago house, and met other people in his community. So the reverberation from these interconnected subcultures around the world have been echoing for nearly 40 years now, bringing an unlikely group of people together to create something really special.”

“I think that Stüssy was definitely a pioneer in creating a community with subcultures around the world” – Ryan Willms

The irony of it all is that when Mr Stüssy departed his brand, he cited creative differences. In a 2013 interview with Acclaim Magazine, he said of his departure: “I saw the next phase that wasn’t a skateboard or surfboard company. A.P.C. was just happening, and you’ve watched agnès b. all those years, COMME des GARÇONS, and Yohji, so I would come back with this vision of the next phase, of evolution, and it was what it was and nobody else wanted it to go any further.” Now, those kinds of brands – the kind that show at Paris Fashion Week and are stocked in Dover Street Market – are selling variations on ideas that Stüssy created, collaborating with his former Tribe peers, and then marketing them to us in a manner that he pioneered.

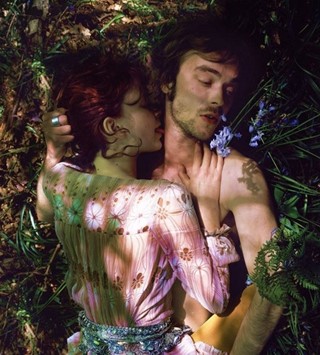

While Stüssy’s rise has not been without its challenging moments – it has skirted dangerously close to becoming an American “mall brand” at points – it remains sought after. For any label to continue to command the attention of swathes of kids, nearly four decades after it first printed its logo onto a blank t-shirt, is a remarkable feat. Throughout those years it has also brought together a bevy of top-class photographers – Ari Marcopoulos, Juergen Teller, Willy Vanderperre and Tyrone Lebon all feature in this book – whilst continuing to influence brands at both ends of the fashion spectrum. An IDEA Book About T-Shirts By Stüssy is an immersive look at this specific kind of genre-blending brilliance – it’s also a template for others looking to catch up.

An IDEA Book About T-Shirts By Stüssy is available exclusively via IDEA and its partner stores and also at Stüssy stores from August 25.