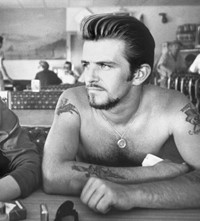

An exhibition of the late actor and artist’s 1960s photography has opened in Los Angeles

- TextMiss Rosen

With the 1969 release of Easy Rider, Dennis Hopper transformed Hollywood filmmaking with the introduction of ‘the auteur’, sparking the American New Wave movement. As director of the landmark counterculture film, Hopper reimagined the classic buddy film as a couple of antiheroes’ road trip across 1960s America, using the then-radical cinéma vérité style.

Easy Rider marked Hopper’s triumphant return to the silver screen after being blacklisted a decade earlier. The death of Hopper’s good friend James Dean sent the young actor into a maelstrom that ultimately resulted in a confrontation with director Henry Hathaway on the set of From Hell to Texas in 1958.

Liberated from the constraints of the studio system, Hopper spent the 1960s pursuing art, first traveling to New York to act in the theatre before being given a Nikon by then-wife Brooke Hayward in 1961. With a camera in hand, Hopper could actively engage in the changing landscape of 1960s America.

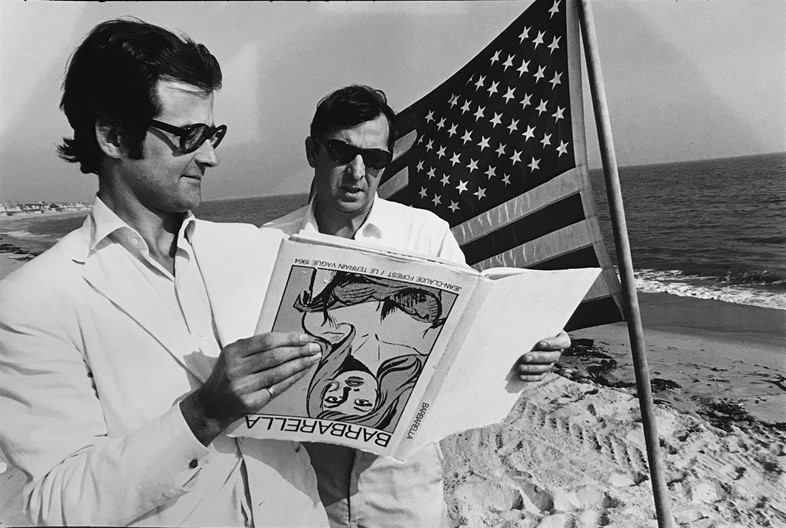

“Dennis was an insider, a friend, and a participant with his camera in hand,” says David Fahey, pioneering Los Angeles photography gallerist who has worked with Hopper since the 1970s and curated the new exhibition, Dennis Hopper in Dreams. “His pictures are unconventional. They have a quirky, fly-on-the-wall kind of way of capturing the moment. I think he tried to free himself from any kind of preconceived idea. He wanted to make an engaging picture as well as capture the significant moment.”

Hopper’s most fertile period of work was made between 1961 and 1967, just as art was emerging from the age of Abstract Expressionism and starting to go Pop. Hopper surrounded himself with artists including Andy Warhol, William Claxton, Joseph Albers, and Ed Ruscha, collecting and even collaborating. His famed 1961 Double Standard photograph was the poster for Ed Ruscha’s first show of gas station paintings; he also appeared in one of Warhol’s earliest films.

“Organic flow is very pertinent. The anthem of the day was Duchamp’s ‘If I Call It Art, It’s Art; or If I Hang It in a Museum, It’s Art.’ It was an atmosphere of anything could happen so anything can be photographed,” Fahey says. “It was all about the accident, the spontaneous discovery, and exploiting the accident. It was not about a preconceived idea. It was about entering into the experience.”

Hopper brought this perspective to Easy Rider, pushing the boundaries on every front, incluing hiring Barry Feinstein, a still photographer who also shot documentaries, as a cinematographer. Feinstein ran a photo lab and had given Hopper his first exhibition in 1961 – which saved many of his negatives and prints from being destroyed in a fire that raged through Bel Air at that time, destroying Hopper’s home.

“When you look back at Easy Rider, you can see photography was very much a part of how he chose to create that film. The story is one thing but how you interpret it with visuals is another,” Fahey says. “It opened the door to one of the greatest eras in filmmaking.”

Dennis Hopper in Dreams is on view at Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles until Match 21, 2020.

Dennis Hopper: In Dreams – Scenes from the Archive edited by Michael Schmelling was recently published by Damiani.