As a new exhibition of his work opens at the Whitney, we provide a four-point guide to the radical art figure

- TextMiss Rosen

As a new exhibition of his work opens at the Whitney, we provide a four-point guide to the radical art figure

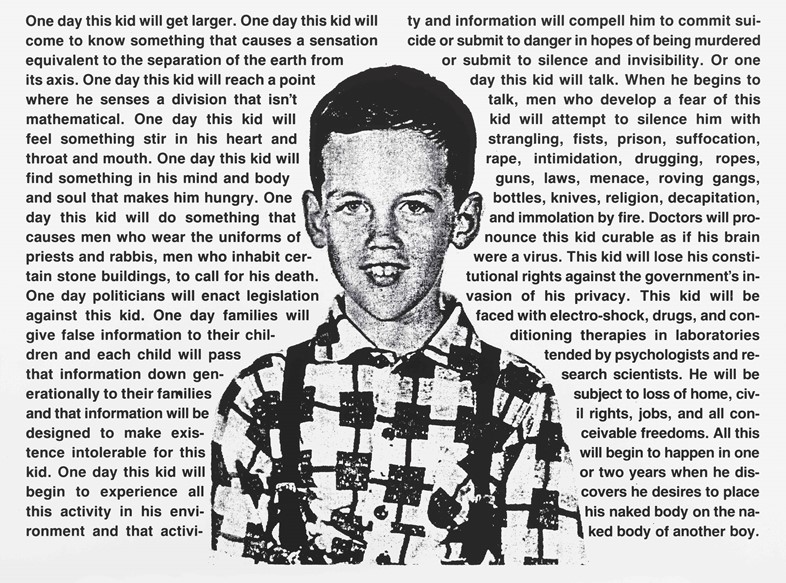

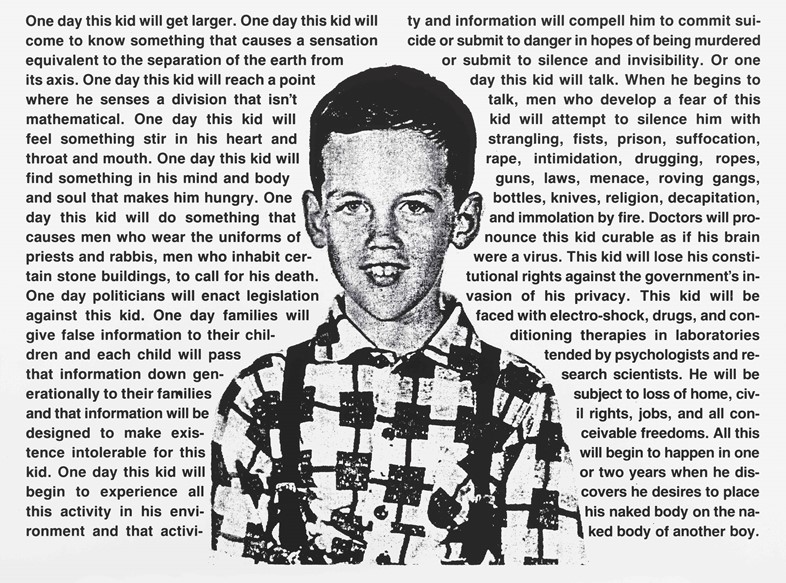

At the pinnacle of his career, American artist David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) was the preeminent symbol the 1980s East Village art scene. Like his contemporaries Kathy Acker, Jenny Holzer, and Barbara Kruger, Wojnarowicz used art as a form of resistance and to unravel the mythical image of America.

Wojnarowicz came of age in New York City, where he was the victim of shockingly brutal childhood abuse. Pushed to the margins, he became a street hustler in his teens in order to survive. By the late 1970s, as a new avant-garde street culture came into vogue, propelled by the DIY ethos of punk, hip hop, No Wave, and graffiti, Wojnarowicz began to create art as a vehicle for political activism, rebellion, and rage against the institutions that oppressed and exploited the vulnerable.

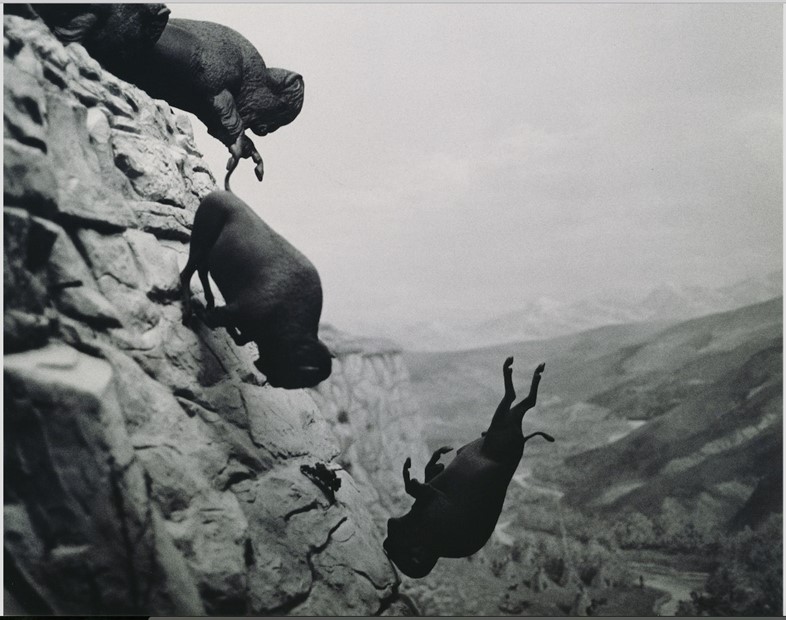

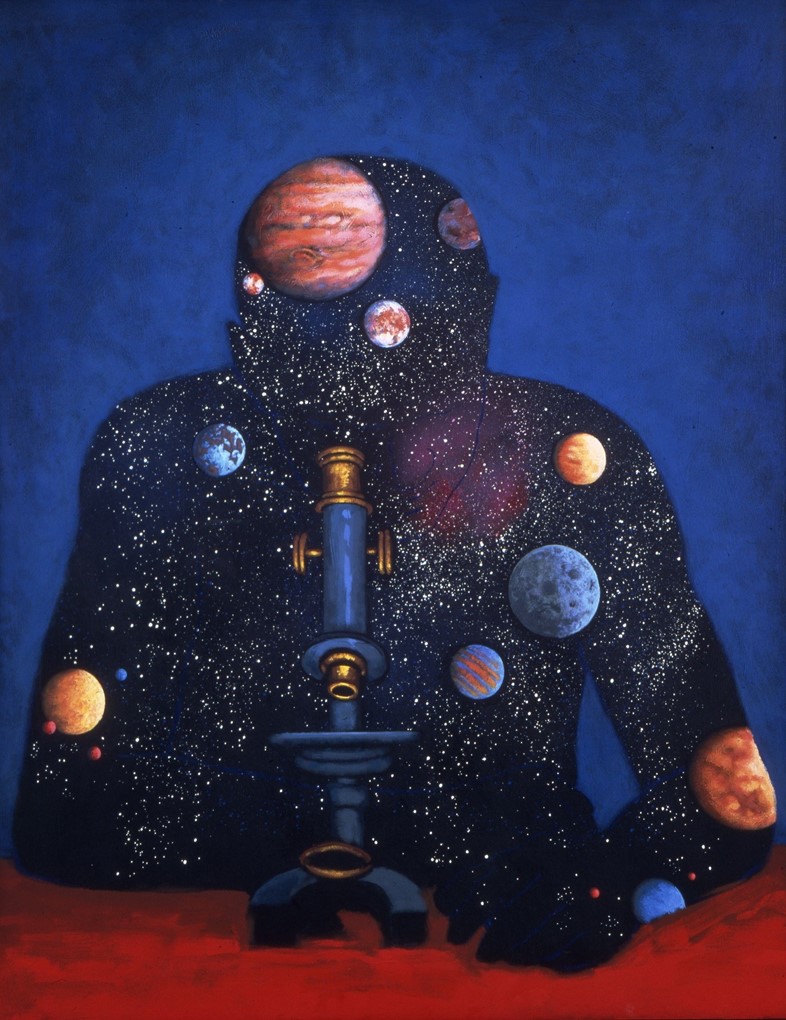

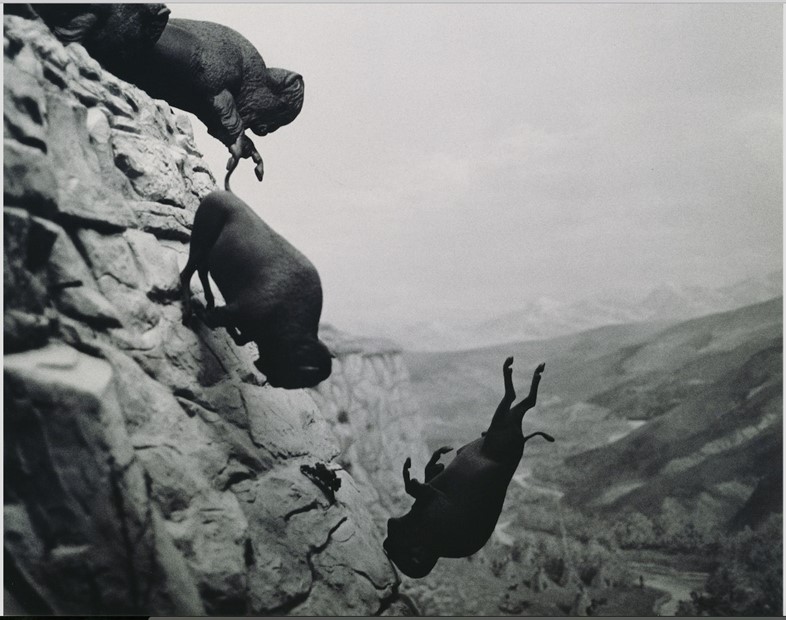

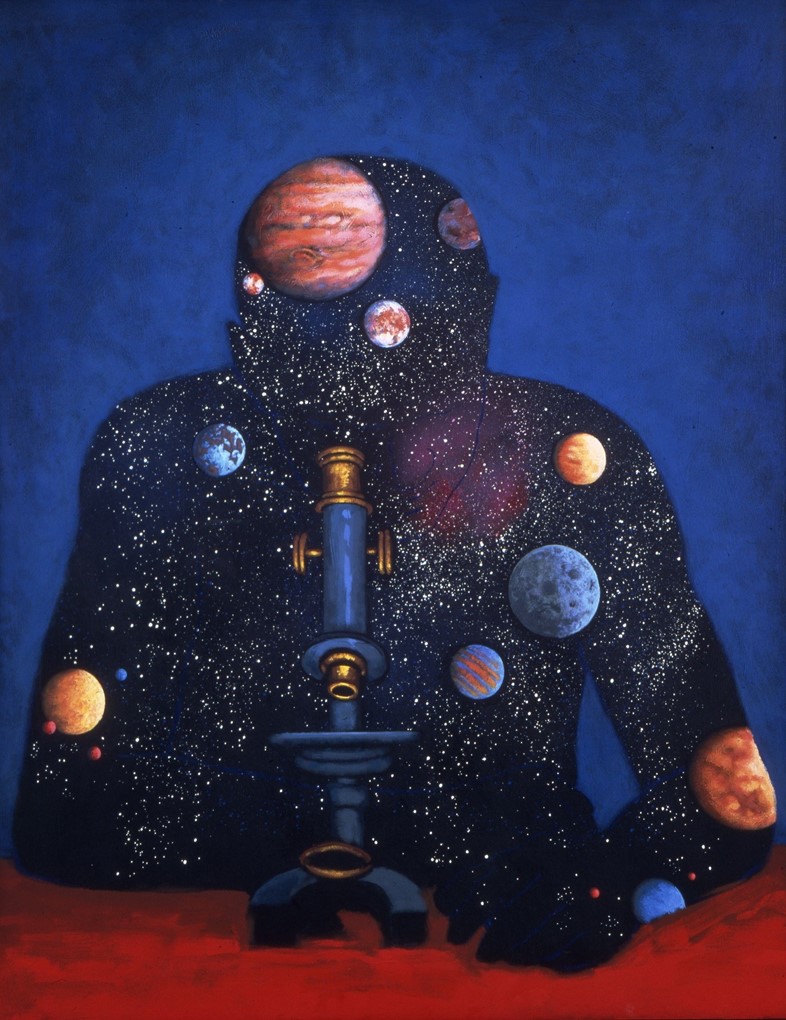

Over a period of about 15 years, Wojnarowicz produced a body of work that was innovative as it was excoriating, working across a range of media – including photography, painting, collage, music, film, sculpture, writing, and performance – using art as a tool of exploration and a weapon to fight the power structure. An AIDS activist until his dying day, Wojnarowicz posed some challenging questions about American culture and history, tearing apart the respectability politics of polite society in search of the truth.

His death on July 22, 1992, which was caused by AIDS-related illness, cut short the life of one most incendiary artists of our time – he was just 37. Now, in celebration of his legacy, the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, presents David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (July 13 – September 30, 2018), which will be accompanied by a catalogue of the same name published by Yale University Press. Here, we spotlight everything you need to know about David Wojnarowicz.

In the years following Stonewall and the Gay Liberation Movement, Wojnarowicz valorised homosexuality in his writing and his art, as well as his personal life. For Rimbaud in New York (1978-79), his first mature series of work, the artist photographed his friends wearing a mask of the 19th-century French poet’s face in different locales such as Times Square, Coney Island, DUMBO, the Meatpacking District, and the West Side Piers when all of these sites were in an abject state of decay.

His decision to photograph at the Piers was a nod to cruising culture: of anonymous sex in a dilapidated setting. The mask, with its cigarette-burn sized slots for eyes, acts as a barrier between the subject and the world, protecting the subject from the prying eyes of the viewer. Here, Wojnarowicz has transformed “Rimbaud” into a symbol of modern life, of the freedom to pick up strangers, shoot heroin, or enjoy a simple meal.

Wojnarowicz came into his own just as the East Village art scene took shape, showing work at galleries including Civilian Warfare, Gracie Mansion, and PPOW before being chosen for the 1985 Whitney Biennial, which focused on the emerging East Village and graffiti movements.

In Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz (Bloomsbury, 2012), his biographer Cynthia Carr wrote, “When I congratulated him, he had such a look of distress on his face. He told me he hated the art world. And then, I believe the exact sentence went: ‘If I were straight, I’d move to a small town right now and get a job at a gas station.’”

Wojnarowicz recognised that his inclusion in the Whitney Biennial gave him a credibility that he did not previously possess – yet fame and wealth only served to contaminate the integrity of the work. Wojnarowicz was not seeking status or material gain; he was a romantic who believed in the transformative power of expression and political efficacy in his art.

Wojnarowicz was deeply ambivalent about the art world, recognising that it could easily become a trap. His relationship with photographer Peter Hujar (1934-1987) allowed him to maintain a critical distance from the industry.

As the AIDS epidemic, which would eventually take both his and Hujar’s life, grew exponentially during a period of willful and dangerous political neglect, Wojnarowicz understood that the art world was just as much a danger to the people as the government. In his essay Postcards from America: X Rays from Hell, he wrote, “major museums in New York, not to mention museums around the country, are just as guilty of… selective cultural support and denial” in dealing with the ever-growing crisis.

In History Keeps Me Awake at Night (For Rilo Chmielorz) (1986), Wojnarowicz shows a man in bed, his form outlined against a map of the world. Above him, a burly white man points a gun directly at the viewer. Within the work are images of money, war, factories, and fallen empires. It’s an evocation of the truth about America that many are just beginning to grapple with today.

He transformed anger into an empowering force, one that compelled him to prolific levels of work that was as conceptually provocative as it was aesthetically innovative. For Wojnarowicz, rage was his muse, guiding him towards not just the creation of powerful work but away from something worse.

In the catalogue, Julie Ault quotes a conversation wherein the artist is asked, “When you’re making art, it’s like a way of not going to the top of the tower and shooting passers by?” Wojnarowicz replied, “Exactly. It’s identifying the impulse to do that and giving it a different form so that I don’t end up going up to the tower.”

David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night is at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, from July 13–September 30, 2018