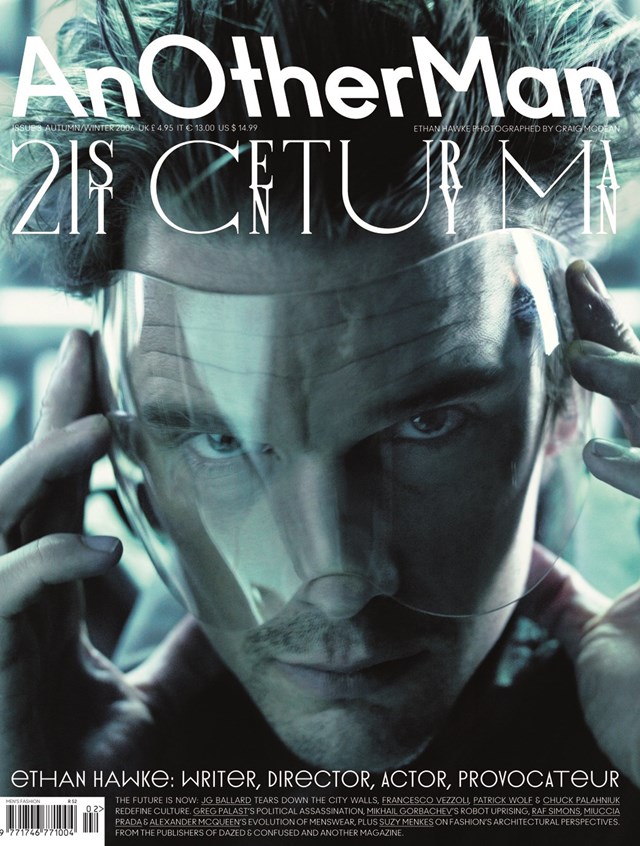

Ethan Hawke

Ethan Hawke is pounding the sidewalk of New York’s Ninth Avenue, a cigarette in one hand, his dog’s leash in the other. It’s almost midnight, but the temperature is still well into the 70s and Hawke is talking fast and free. He’s been chatting for a couple of hours at his local Chelsea cafe, drinking red wine and coffee, and now, he is reminiscing about his friendship with River Phoenix. The pair made Joe Dante’s The Explorers together in 1985 when they were just 15 and neither had made a movie before. Hawke remembers how they became firm friends during the shoot, and how they talked fiercely between themselves, as 15-year-olds do, about staying true to yourself and what it meant to be a good actor. Hawke recalls how Phoenix – young, smart and ballsy – was steadfast in his disdain for Hollywood bullshit. Interviews were for pricks. Publicity was for morons. Playing the game wasn’t cool, and taking a bad role in a film just for the sake of it – for the cash – was totally off-limits.

“When I was young, wanting be famous was like saying you wanted to be mediocre,” Hawke says, his patter quick and spirited. This evening, his baggy pants, loose checked shirt and old trainers give him the look of a veteran skater. He’s 36, and looks good for it.

“If you wanted to be fucking serious, like a great artist, you wanted to be obscure. If you were celebrated, you were obviously a phoney. That attitude doesn’t exist now, I don’t see that anymore. I meet all these young actors who are dying to be on magazine covers.”

Later on, as we sit down on a bench to smoke a cigarette and check on Hawke’s dog, who’s tied up outside the cafe, he softens his attitude and admits that there are indeed some young actors who he likes and whose singular approach to the profession impresses him. Gael Garcíía Bernal is one, and Mark Webber; the star of Hawke’s new film, The Hottest State, is another. It’s just that Hawke is fed up of encountering young actors with their publicists at their side – “and if not right there at their side, then on their mind, anyway.”

It’s been a long day. Hawke spent the morning on the set of Serpico director Sidney Lumet’s new film, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, in which he stars alongside Philip Seymour Hoffman and Albert Finney. That done, he dashed across town and switched caps (“moonlighting” he calls it) to oversee the final stages of the edit of his second movie as a director. The Hottest State is an adaptation of his 1996 novel of the same name, a Lower Manhattan tale of a confused 21-year-old’s first, awkward love affair in the wilds of the city. Thinking of the film, Hawke feels confident about its quality but also nervous about its future. He says that The Hottest State is a straighter affair than his 2001 experimental digital movie, Chelsea Walls, and the day after our interview, he explains, a rough-cut will be scrutinised by the programmers of the Venice Film Festival. He admits that he harbours a romantic dream of taking this new, deeply personal film to the same Italian film festival where Dead Poets Society was released back in 1989 when he was just 18 years old and barely anyone recognised this new face from New Jersey.

“In a way, it was overnight success,” Hawke considers, as he casts his mind back 15 years. “But I got to share it with a group of peers. We had the experience of being wildly successful, but at the same time it was always ‘we’ instead of ‘I’. I wasn’t ‘Ethan Hawke’, I was ‘one of the of kids from Dead Poets Society. The film’s director, Peter Weir instilled in us a real mistrust of celebrity and faith in the integrity of cinema.

“There were conversations that (Poets star) Robert Sean Leonard and I had when Dead Poets Society came out that I’m not sure young actors have today. I remember Robert was asked to do a Gap ad, and he said, ‘No, no way!’ And then, when he said no, they asked me, and I secretly wanted to do it – I think Annie Leibowitz was the photographer – but I couldn’t do it because I knew Bob would think I was such a sell-out. Now, everyone’s doing ads.”

A lot has happened since then. After Dead Poets Society came White Fang, Hawke’s first true lead role, and a clutch of other so-so early movies such as Dad and Alive, which propelled his name a little further into the public consciousness and his face on to the bedroom walls of a more sensitive type of teenage girl. Like many a fresh-faced actor to come before and after, Hawke enjoyed a brief moment as Hot Young Actor – a peril which he survived and sidestepped by choosing more interesting roles such as 1992’s offbeat, Norfolk-set Waterland, in which he appeared opposite Jeremy Irons and Sinééad Cusack. His reputation grew slowly. In 1994, in Ben Stiller’s Reality Bites he was the ultimate mid-90s, goatee-sporting Gen-X provocateur. A year later, he elicited more sympathy as Jesse – the American backpacker who spends a summer’s night in Vienna with Julie Delpy – in Before Sunrise. That film was the first volley of an ongoing collaboration with director Richard Linklater, and a film that further confirmed Hawke as a frenetic, charismatic and, crucially, thinking acting spirit. He was developing a reputation for playing characters with a smart mouth and a naked brain, confirmed again when in Michael Almereyda’s Hamlet, he delivered the “To be or not to be” speech in a Blockbuster video store as a rich, upstart wannabe-filmmaker.

Slowly, the slacker symbols – the angsty chit-chat, the goatee and the greasy hair – have disappeared from Hawke’s films. But the self-questioning attitude has stayed with him. Perhaps the most revealing of his recent movies was 2004’s Before Sunset – the sequel to Before Sunrise – in which he again plays the character of Jesse, by now a successful novelist, who bumps into Julie Delpy’s Celine while on a book tour of Paris. It’s the first time the pair have seen each other since saying goodbye in Vienna nine years earlier and the next hour-and-a-half is taken up with an animated conversation about growing up, becoming an adult and the difficulty of staying true to your ideals. Hawke says he and Delpy had a hand in much of the dialogue in Before Sunset (they’re credited as co-writers), and it’s clear from our conversation that these are the same issues that continue to be of prime concern to him.

“Most actors end up dead, you know? And if not dead, then spiritually dead,” he says. “It’s easy to be young and idealistic. It’s harder when you get hit with the brass tacks of living. The easy thing to say is, ‘Well, I’m paying the bills...’ But what’s hard is to put your money where your mouth is and contribute – and to contribute at the level at which you’re capable of. I still have high hopes, I still have a strong desire to contribute, and the only way to do that is to grow and to learn and to get better. It’s hard to do, and life beats you up a little bit.”

Hawke has written two novels, The Hottest State and Ash Wednesday. He’s founded and disbanded a successful theatre company, Malaparte. He continues to work in theatre, and will take to the stage this autumn at New York’s Lincoln Center in The Coast of Utopia, Tom Stoppard’s trilogy about the Russian revolution. On the personal front, he has two children from his six-year marriage to Uma Thurman, and he explains the late hour of our meeting is because he wanted to go home first and put his kids to bed.

Hawke’s friendship and ongoing collaboration with the director Richard Linklater, remains a bedrock of his work. He has a cameo in Fast Food Nation, the film of Eric Schlosser’s book, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May, and is the sixth movie that he and Linklater have made together. He talks about another, longterm project that the pair are working on: each year for the past five, Linklater has made a short film in which Hawke and the same child actor play out the roles of father and son. The child was six years old when they started the film, and they plan to repeat the same process once a year until the boy is 18.

“It’s the weirdest thing I’ve ever worked on. We write it as we go. It will feel like a documentary, and we’re all bringing to it our childhoods and our experiences as parents.”

What exactly makes for a good interview?” Hawke interjects; not for the first time switching the conversation back to me. By now, considering that we’ve only been together for an hour-and-a-half and it’s not me that’s the one being interviewed, he knows an unusual amount about my life, and the questions keep coming.

“Who’s the most interesting person you’ve interviewed?” he continues, before adding, “I always wanted to be a journalist, I think I’d like that.”

This might sound like well-focused charm on Hawke’s part, but in truth, he’s simply curious and obviously interested in other folk and the world around him, which perhaps partly explains his desire to write and direct. While talking outside the cafe, the young waitress comes out and plants a long kiss on the mouth of her boyfriend, who’s sitting outside and straddling a motorbike. “Oh my god, how weird,” Hawke suddenly interrupts. “I come here all the time, and I’ve never seen her with a guy before. It’s funny how you only ever see one part of most people’s lives.”

He wrote his first novel, The Hottest State in 1996, and it’s good – a semi-autobiographical, first-person account of a doomed love affair. It’s clear the book’s narrator, 21-year-old William Harding, is Hawke’s alter ego. Like Hawke, Harding is an actor who left Texas as a child when his parents split, and then moved with his mum to New Jersey. It’s a novel that’s defined by 20-something curiosity and paranoia about women, relationships and the shadow of parents, and it’s full of smart insights and funny episodes. It’s a good thing that Hawke has turned the book into a film; it should make for a witty coming-of-age movie.

“When I first started acting, my real dream was to be a writer,” Hawke explains. “That’s what I thought I was going to be, and I went along to some auditions to earn some money. Then the acting thing went really well and started to create a lot of opportunities, and it still does. It’s a tremendous amount of fun, and I get to meet a lot of smart people, but I constantly wish I was writing more.”

Of course, some have sneered at Hawke’s desire to find success as a writer, but The Hottest State, as Hawke proudly points out, is now “in its 20th printing”. In 2001, followed the more ambitious Ash Wednesday, which he considers “a better book”. Critics tend to agree and have widely praised his prose with its hints of JD Salinger and desire to nail the yearnings and crises of the modern American man. Like William Harding, his protagonist, Jimmy Heartsock, is a guy trying hard to overcome his shortcomings and stay attached to the woman he loves.

“I wanted to show that I wasn’t a dilettante,” Hawke explains of his second stab at writing a novel. “It’s so eccentric to other people that an actor is writing a book that I felt I needed to write another quickly to show that I wasn’t just having a hoot and that I was serious about it.

“I remember I got a letter – I hope he won’t mind me saying so – from Graham Swift, who I had the privilege of meeting once because he wrote Waterland. He wrote me the funniest letter saying that he had read The Hottest State, and something along the lines of how disappointed he was in me because I had written a book and he loathed the idea of celebrity fiction and it bugged him. But then, he said that he was quite surprised and thought it was ‘not half bad’!”

This touches on a theme that emerges several times in our conversation: the power of peers and mentors in Hawke’s life, from River Phoenix and Robert Sean Leonard to Peter Weir, and, of course, Richard Linklater. Talking of other actors, he contrasts his own trajectory – quick and young – to that of his current co-star Philip Seymour Hoffman, an actor who spent years impressing in small character roles before only recently landing more substantial parts such as the one that won him an Oscar in Capote. “He’s had a harder road home than me,” Hawke considers, even sounding a little embarrassed. “When I was 18, I was playing the lead in White Fang in Alaska, learning my lines in the car on the way to set. Whereas he has had to fight for every line.”

He talks of Albert Finney too, his other co-star on the new Sidney Lumet picture, and how in conversation the veteran actor harbours a much greater fondness for his theatrical career than his film work. “He kind of lights up when he talks about theatre.” Hawke, too, admits that he responds so much better to fans of his stage-work than to “somebody who comes up to you and says: ‘Oh, I loved you in Reality Bites.’” For him, theatre is the real deal, where the real graft is done (“without sounding corny, I think it’s my first love”). It’s also a matter of pride, to be successful in theatre as well as cinema. Stage actors can’t ride on the skewed values of Hollywood, where privilege and youth, beauty and hype rule the day. Theatre is about craft, pure and simple. And that suits Hawke just fine.

As we continue to talk and drink, the conversation darts all over the place. Hawke’s a good storyteller. There’s the one about his good friend, an actor, who at every audition used to leave behind a briefcase containing a dictaphone so that he could return later, collect it, and listen to what the director thought of him. “He has a tape of Francis Ford Coppola saying that he’s a terrible actor – he wept.” Then there’s the one about another friend who was recently having a phone conversation with one of Bob Dylan’s sons – “Jakob or Jesse, I can’t remember, they both work in the film business” – and he realised that Dylan himself was strumming his guitar in the background, much to his son’s annoyance: “He hears the son say, ‘Dad, will you give me a break,’ but Dylan carries on until the son can’t concentrate on what he’s saying and just shouts, ‘Dad! Shut the fuck up!’”

A friend pops into the cafe to say hello after recognising Hawke’s dog outside. It turns out that it’s one of his fellow actors from the Tom Stoppard play, and they talk for a bit about the research material that they’ve been sent by the Lincoln Center. “It’s part of my job now to read Turgenev and Dostoevsky. I get to sit around on a film set and instead of flicking through a comic book, I can read and consider it work.”

Work and friends go hand-in-hand for Hawke. Just think of Linklater and the 12-year project to which they’ve both committed; “You could only do that with someone you know well and who you can be confident you’ll be friends with in ten years time.” And think back to some of his smaller, more personal films. His 2001 directorial debut, Chelsea Walls – “a weird little DV movie” he calls it – was made from Nicole Burdette’s script (and based on her play), but its subject – it’s an inquisitive slice-of-life piece that dips into the lives of about 30 people staying at the Chelsea Hotel – is pure Hawke. Two of its cast, his friend Robert Sean Leonard and his then-wife Uma Thurman also joined Hawke the same year to make Linklater’s Tape. If any film offers a window into Hawke’s soul, it’s this one: it stars only the three of them, takes place in a dingy motel room and deals darkly and claustrophobically with failed friendships and doomed relationships. It’s intimate, challenging and, crucially, allowed him to work with his best friend and wife.

“A lot of actors get by in life by having a nice smile,” Hawke ponders as we leave the cafe before eventually parting on the corner of his street. It’s past midnight now, and he plans to be in the edit suite early in the morning to polish off the final touches to The Hottest State.

“There’s a line in my first novel that my grandmother once said to me: she used to tell my mother that she prayed everyday for her to have fat legs because she believed that women who were good-looking give themselves permission to be uninteresting.

“I pray for the same thing for my daughter and my son. It’s a hard thing to learn, but without a little suffering, without a little challenge, we all just want to eat cupcakes, smoke cigarettes and get laid: none of those things make a valuable life.”