As Dark Waters hits UK cinemas, director Todd Haynes opens up about the influences and impact of his film about one man’s battle with a US chemical giant

- TextDaisy Woodward

The work of American director Todd Haynes is, on the whole, experimental, colourful and emotionally wrought – from his pioneering early contributions to the New Queer Cinema movement, like 1991’s Poison, to 1998’s outré ode to glam-rock, Velvet Goldmine or, indeed, the sumptuously shot 1950s period pieces Far from Heaven (2002) and Carol (2015). Which is why his latest endeavour, Dark Waters, may come as somewhat of a surprise. A gruelling, sludge-paletted whistleblower drama, based on the true story of a corporate lawyer’s battle against one of the world’s biggest chemical manufacturers, the film is a far cry from anything Haynes has made before.

Haynes himself was taken aback when Dark Waters’ star and producer, Mark Ruffalo approached him to direct the feature. “It was so interesting that he thought of me for it,” he tells Another Man, ahead of the film’s UK release, “and I was so honoured, because it’s the kind of film I really love: those darker, more disquieting examples of the whistleblower genre from the 70s”.

Ruffalo, a keen environmentalist, was stirred into action after reading a 2016 New York Times exposé about the doggedly determined lawyer, Rob Billot, and his quest to hold chemical giant DuPont accountable for withholding information about one of its highly toxic chemicals, PFOA, which poisoned an entire West Virginia community. (Used for non-stick pans, waterproof coating and an alarming number of other products, PFOA is directly linked to six severe illnesses). “When I read the piece, I was astounded,” recalls Haynes. “It couldn’t be more relevant for a film – it had so many shades of complexity.”

The story begins with a horror-tinged preface which sees a group of teens swimming in a contaminated lake in the 1970s, before fast forwarding to the late 90s and the beige Cincinnati law firm where so much of the action – and lack thereof – takes place. Billot is a modest, unassuming man who’s just been made a partner in the business, which specialises in defending corporate clients (including DuPont) against the very type of environmental lawsuit that he himself will soon be launching.

His change of heart is the result of a weather-worn farmer (a bushy browed Bill Camp) who marches into the office with a pile of stomach-churning video tapes documenting his swiftly depleting herd of apparently poisoned cattle in Billot’s own hometown of Parkersburg, WV. He’s sure it’s down to the local DuPont plant and its dumping of toxic waste, but doesn’t know how to prove it. Compelled by the evidence (and the farmer’s connection to his grandmother), the cautious Billot starts to investigate, opening up a horrifying can of worms in the process, and setting the wheels in motion for the groundbreaking class-action lawsuit that would change US legislation forever.

“I was looking at the great 70s paranoia filmmaking attributed to Alan J. Pakula and Gordon Willis – the way those movies really put you inside the process of discovery,” Haynes says of the films that inspired his slow-burn approach. “They trust in audiences’ patience and attention to detail and nuance – you don’t particularly love the characters, as you might in a movie like Erin Brockovich, there’s something else going on.”

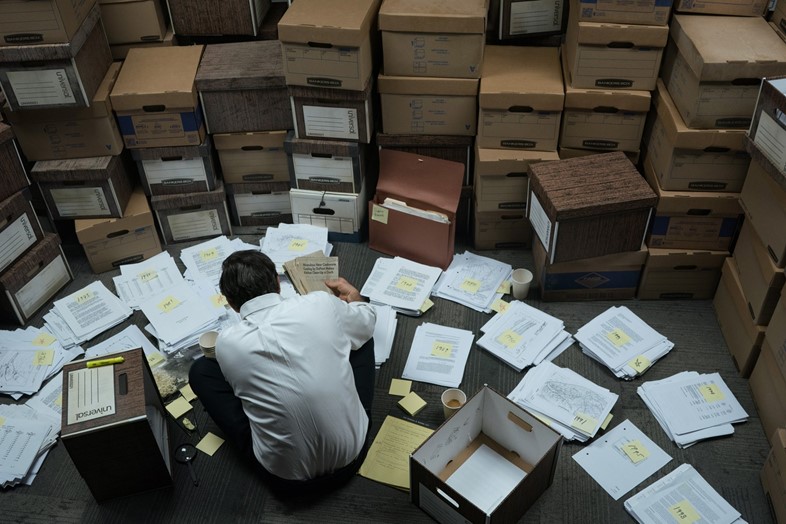

This, he explains, is achieved by confining the audience to the same mental and physical space as the protagonist. “In films like The Parallax View and Klute and later movies like Silkwood or The Intruder, the spaces and locales that these characters occupy, and how much they appear to be trapped within them, really sticks with you. It’s a visualisation of the systemic pressures and burdens they’re undergoing, and as the stories get bigger, it’s almost like the walls are closing in and their lives are getting smaller – which is very much how Rob described his experience.”

Billot’s involvement was key to the filmmaking process as a whole. He not only consulted on the script but also made himself available to Ruffalo, in his masterful embodiment of Billot’s grim perseverance, and Haynes throughout pre-production and filming. “We’d heard that Rob was extremely guarded about sharing his experiences, but I found him to be anything but,” Haynes enthuses. “At first I was wary about having the guy who we were making a film about around, but I very quickly became dependent on it.”

Haynes was moved to notice the effect that Ruffalo’s performance had on the man he was impersonating. “Mark had to reconfigure himself inside a very different temperament to his own – and a lot of the very outspoken and passionate roles we associate with him. Rob is tentative, cautious, hesitant to smile – he seems to feel the weight of the world on his shoulders. But as we were making the movie, and Mark was becoming Rob, Rob started to change physically himself, as if he was being unburdened by the very fact that his story was finally getting told.”

And it’s a story that needed telling – in spite of the success that Billot has so far accomplished, there is still more to be done. “There remains an entire family of these ‘forever chemicals’ (once they enter the bloodstream, they never leave) being utilised in the marketplace and it needs legislation,” Haynes explains. “The film has really drawn attention to this: there are bills in the House and the Senate now, bills being sponsored by Republican senators in Florida.” Moreover, it’s an important reminder that individuals really can make a difference in a seemingly unshakeable system that prioritises money over people. “This story reveals all these grim cultural and social realities and forces us to absorb them,” Haynes says as his final sign off, “so the film’s message feels particularly important as we look ahead this election year and make decisions about our safety and health”.

Dark Waters is in cinemas nationwide from February 28, 2020.