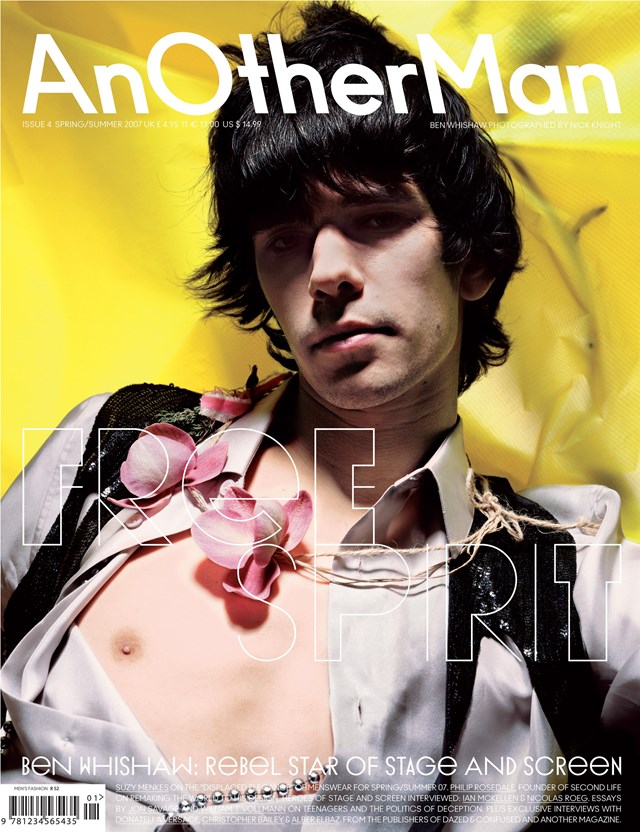

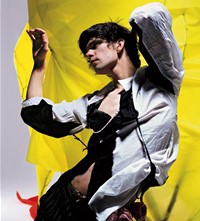

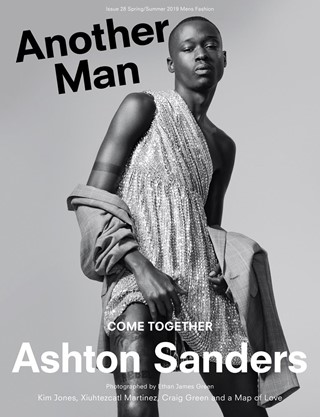

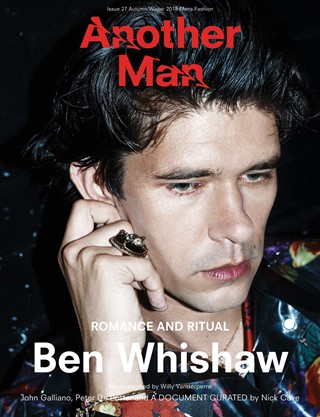

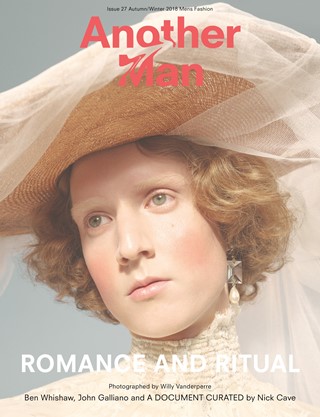

Ben Whishaw

Ben Whishaw is intense in person and he’s intense on screen. He stalked pre-revolutionary France in eery silence for Tom Tykwer’s Perfume: The Story of a Murderer. He stole the role of theatre’s most troubled teenager, Hamlet, at London’s Old Vic when he was just 23. And now, at 26, he’s playing Bob Dylan at his most poetic for Todd Haynes’s experimental take on the singer’s life, I’m Not There. It was exactly the sort of role he yearns for: tough, introspective, complex.

“It’s joyous to spend time thinking about Bob Dylan and listening to his music,” says Whishaw, who reflects just one of the musician’s many faces in Haynes’s new film. “He’s someone who has staunchly refused to be categorised or pinned down as one thing.”

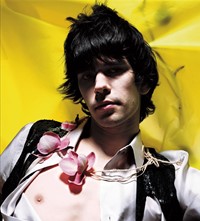

Whishaw is British cinema’s most intriguing young actor. He’s too smart to be a pin-up, and yet he has a vulnerable, attractive beauty. He’s too intelligent to furnish anything but the most challenging of films, and yet he’s already been entrancing huge audiences worldwide with his turn as a near-mute serial killer in Perfume. His performances display a hint of the disturbed, a touch of the autistic, and a dash of the childlike genius. Directors adore him. “There’s a substantially older soul in this younger body,” says Tykwer. Adds Haynes, “That kid is just unbelievable, there’s no telling where he could go from here.”

Over lunch in London in January, and with the exhausting release of Perfume only a few weeks behind him, Whishaw fidgets the entire time. He plays with the buttons on his shirt and toys constantly with his knife. Combine this with a habit of rolling his eyeballs speedily from side to side as if considering a philosophical problem, and you realise you’re in the company of a young man who can’t help but exude an aura of nerves, tension and thoughtfulness. If you look at the roles he’s played – Hamlet, Dylan, Jean-Baptiste Grenouille in Perfume, a small role as Keith Richards in Stoned, an immature drug dealer in Layer Cake – they’re all mercurial, wispy and damaged. If you take a close look at him in the flesh – piercing, vulnerable, good-looking – you can see why he’s so in favour for the sort of roles he’s becoming known for.

He’s full of nervous energy, always stumbling to explain himself, and regularly apologising for not making sense. “Is this a bit boring?” he worries at one point. Mostly though, he’s smart and reflective, and, with a bit of prodding, happy to recall his career so far. It’s his film work that’s currently grabbing headlines, but it’s his love for theatre that shines through. It’s apparent in conversation: he mentions in passing that he was comparing notes recently with British actor Simon Russell Beale; later, he jokes that he wishes he could dismiss interviews with the same force as Michael Gambon.

“It’s funny because when I go to theatre auditions people say, ‘Oh, you’ve done an awful lot of film, you’re really a film actor,’” says Whishaw, tucking into the most economic of lunches: a bowl of soup. “And then when I go and do a theatre audition they say, ‘Oh you’ve done an awful lot of theatre, you’re really known for that.’ But I feel like I’ve actually done equal amounts of both, so I feel quite comfortable with the two.”

The word on Todd Haynes’s new film, I’m Not There has been mysterious ever since it was first announced two years ago. From the beginning, Haynes stressed that I’m Not There would be a film about Bob Dylan’s life and music, but not a traditional biopic in the way, say, Walk the Line was about Johnny Cash or Ray was about Ray Charles. Instead, it’s more helpful to think of less obvious, more imaginative takes on music biography, such as Gus Van Sant’s Last Days. For a start, in I’m Not There no less than six actors play seven versions of Dylan (Christian Bale has two cracks of the whip), and each of them reflect a different aspect or mood of the ever-mutating musician. Moreover, one of the six actors is a woman, Cate Blanchett, and it was even rumoured at the casting stage that either Beyoncé Knowles or Venus Williams would play Dylan (neither did in the end). Amusingly, even Richard Gere plays one “Dylan”.

To give his new film some context, it’s worth remembering that it was Haynes who, 20 years ago, made Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story – a work that blew film biography out of the water, turning it into a plaything of the experimental indie auteur. That spine-tingling and crazily inventive 43-minute film recounted the life and death of Karen Carpenter using only Barbie dolls, music and television clips, and contrasted the sweetness of the Carpenters’ music with their troubled home life and a corrupt Nixon presidency. Following a successful lawsuit from Richard Carpenter, the film is no longer in circulation (although you’ll find it easily on the internet). With this in mind, it was never likely that Haynes would craft a stodgy, formulaic Hollywood biopic about Dylan – an artist who he freely admits to worshipping, and who has taken the rare step of giving Haynes permission to use his music in the film.

“The film’s a big sprawling concept that brings together all the different facets of Dylan’s life,” Haynes explains from his home in Portland, Oregon. “It allows these facets to maintain their distinctiveness rather than forcing them into a single arc that biopics so often suffer from. It seems cruel to distill a person’s whole life into a few narrative notes.” Whishaw plays a version of Dylan from the years 1965 and 1966, a time when the singer was giving increasingly loopy interviews to the media, and channelling the influence of Arthur Rimbaud and other French Symbolist poets in his conversation and lyrics.

Whishaw’s Dylan is “Arthur”: he pops up throughout the film, always alone in front of the camera, standing against the wall and answering the questions of an anonymous interrogator from behind the lens. It’s only late in the film that it’s revealed that Arthur has been arrested, and the questions are actually coming from the police.

“I remember the first time I encountered the texts of these rather famous interviews from the mid-60s,” Haynes recalls. “They sound remarkably like the lyrics he was writing at the time, there was a lot of playfulness, absurdity, surrealism and, one suspects initially, a kind of refusal to address the literal questions being asked. But when you really look at his answers he’s answering them on so many levels – but with a playful and irreverent style that was completely his own.”

Whishaw first met Haynes when the director was casting the part of Arthur. He visited Haynes at home in Portland, where he’s lived for several years since leaving New York, and the two hit it off straight away. To explain his ideas for I’m Not There, Haynes told Whishaw a story about how in New York, he’d once seen a live show by a man who dressed up as Joni Mitchell, wearing a wig, sitting at a piano and singing. “Apparently, on the one hand, it was absurd and ridiculous and funny, but on the other quite moving,” Whishaw explains. “This guy is able to channel something of her spirit or whatever. I think Todd wanted to do a similar sort of thing. He’s not asking anyone to believe that Cate Blanchett is Bob Dylan, but there’s something that removes the audience from that expectation, so they can experience it differently.”

Whishaw might now be playing Dylan for one of America’s most imaginative filmmakers, but not long ago, he was a teenager who didn’t care about much else than after-school theatre. Born in 1980, Whishaw says that he always cared more about acting than the traditional pursuits of the classroom. “I’ve erased a lot of my school memories, I never think about it. I don’t think I was particularly happy, and it wasn’t a very nice school really.” He grew up in Bedfordshire, not far north of London, and threw himself head first into the life of Big Spirit, the local youth company in nearby Hitchin, Hertfordshire when he was just 13 (“Not that young really,” he says). “I’ve never come up with a good story about how it all started,” he reflects, shrugging his shoulders, not in the least bothered about giving his tale a good spin.

“I just knew that I wanted to act, but I can’t remember exactly why or how. And nobody ever said: you can’t do that. My parents never said that it wasn’t a good idea.” He raves about youth theatre and everything he learnt there. “We were doing really amazing things. Adaptations of novels by Primo Levi. Brecht plays. We devised adaptations ourselves, and had an amazing director with extraordinary ambition and interest in what was happening in theatre at that time. We’d go and watch plays in London, and then copy people. I miss the uncomplicatedness of acting at youth theatre. It was just about the pure joy of doing it.”

The bridge between teenage bliss and the first glories of professional life came quickly for Whishaw, with little time for struggle or worry about what the future might bring. He doesn’t remember being much of a star at the Royal Academy for Dramatic Arts, where he went to study when he was 20, but he was “given character roles, supporting roles, which I loved”. When he left RADA, he started firing off letters. “I still had this mission to do theatre, I was desperate to do it.” He soon found work and had a small role in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials in early 2004 at the National Theatre in London when he was invited to audition for Trevor Nunn’s new production of Hamlet at the Old Vic.

“I never believed that I would leave drama school and play Hamlet six months later,” he says. “Never for a second.” And yet, from April to July 2004, Whishaw attracted rave reviews for his performance as the Danish prince in a production that took literally Shakespeare’s suggestion that Hamlet is a brooding, teenage university student. Whishaw’s Hamlet – defined by the actor’s feather-like frame and prominent jaw bones – was not a strong-willed young man full of revenge, but instead, a grief-stricken teenager, not much more than a kid who was damaged by familial strife and listened to The White Stripes to blank out what was happening at home. “I don’t even remember finding it particularly difficult,” Whishaw says, not in a spirit of arrogance, but rather to explain how young he was then and how quickly it all happened. “I think in a way, I was still quite innocent about the world and the world of acting and theatre. I didn’t really understand the risk and what could be lost. It could have been a catastrophe.”

Nunn took a gamble on Whishaw, and it paid off. It’s a pattern repeated in Whishaw’s relations with film directors. When Tom Tykwer, the German director of Run, Lola, Run, was looking for someone to play the lead role of Jean-Baptiste Grenouille in Perfume, he met around 100 actors until a casting director suggested that he go and see Whishaw in Hamlet at the Old Vic. “That was my moment of discovery,” recalls Tykwer. “I’d been looking for the right guy for over a year. The problem was that we were looking for such a complex set of skills, it’s quite a contradictory character. What I saw was the most contemporary, lively, interesting Hamlet, and performed by a 23-year-old guy. I wanted to make a modern film in a period disguise, so he was exactly what I was looking for.”

Whishaw’s performance superbly indulges the sheer weirdness of Jean-Baptiste Grenouille – a baby dumped at birth in a stinking fish market in 18th-century Paris, and who survives the vicious regimes of an unforgiving orphanage and a gruelling tannery to develop the most sensitive nose in all of Europe, going on to become a master perfumier. In his quest to concoct the perfect fragrance, he becomes a serial killer along the way. Whishaw plays the role almost in absolute silence, presenting a character who’s certainly locked in his own bizarre world, but not someone who we’d ever perceive as simply evil. Talking to Tykwer, it’s clear that filmmakers are drawn to Whishaw not only because he’s a good actor but because he’s a good talker too, someone with whom they can debate a character and the direction of their work.

“We crawled into some peculiar tunnel together and never left it,” describes Tykwer. “I needed someone who enjoyed talking as much about the entire concept of the film as they did about character. The two are inseparable. As much as you have to talk about this guy’s identity, you have to know what kind of movie we’re trying to make.”

It’s no surprise that Whishaw has recently been working with Pawel Pawlikowski, the Polish-born British filmmaker whose features such as My Summer of Love and Twockers are crafted by way of his background in documentaries: he researches his films intensely with his actors, filming them in real situations and fully developing their characters before writing a full script or filming the movie proper. His latest film The Restraint of Beasts, is an adaptation of the Magnus Mills novel about three fence-builders from Scotland – played by Whishaw, Rhys Ifans and Eddie Marsan – who go to work in Yorkshire. “I’m the foreman,” says Whishaw. “Nothing much happens but they accidentally start killing people. We don’t know how the film is going to end because Pawel hasn’t finished writing it.” At the minute, however, the film may never be finished: production was halted halfway through when a personal tragedy hit one of the core crew. “Pawel was totally unlike anyone I’d worked with before,” Whishaw says, relishing the film’s unusual process, which involved him, Ifans and Marsan spending several weeks learning the trade of their characters. “I’m pretty good at building fences now, not bad at all.”

He’s pretty good at making movies too. In a few short years he’s gone from being an interesting presence in the background of a few British films – he was a twitchy guy in the back of a classroom in Roger Michell’s Enduring Love, and he appeared all too briefly as Keith Richards in Stoned, Stephen Woolley’s film about the death of Brian Jones – to being celebrated by serious, inventive filmmakers such as Tykwer, Haynes and Pawlikowski, in Britain and beyond. His work in theatre continues to go from strength to strength too: in autumn 2006, he played Constantine in Chekhov’s The Seagull at London’s National Theatre. Now he’s even being offered film roles by people who’ve never even met him, which he finds flattering but also troubling.

“I keep – well, not keep – I now get scripts occasionally from people saying, ‘We’re offering you this role.’ And I can’t imagine just saying, ‘Yeah, sure, I’ll do your part,’ and then turning up on the first day, without a discussion, without a relationship. I’m always a bit suspicious because I think that if I was making a film I’d want to meet the actors before I offered them something.”

Just as his directors are thankful of his commitment and readiness to debate and discuss his work, so Whishaw wants the same from the directors he works with. You sense that the spirit of theatre – of collaboration, of closeness, of locking heads together intensely for a period of time – is deeply ingrained in him. He loves working in theatre, and he wants to have the same experience when he makes films. You feel this strongly when he speaks about his relationship with Tom Tykwer. He wants a meaningful collaboration with a director – or nothing at all.

“We were quite close by the time we started shooting. And I think I always look for that now. It’s important to me that the experience is a stimulating or enriching one. I didn’t read the reviews of Perfume, and in a way that doesn’t matter because the film was such a wonderful experience to make that I feel I at least got something out of it. I’m proud to be a part of it, so in a way it doesn’t matter what people think.”

And what of the attention that success brings? And the responsibility of having to carry a film like Perfume, appearing on screen for almost the entire film and then having to be its ambassador in the world at large? He’s clearly quite a sensitive soul; doesn’t it weird him out just a little?

“Yeah, I never really think about that because I find it frightening, and then I just freak. So I try not to dwell too much on the fact that it’s a lead role, and just keep my head down and do it. That’s the only way I can cope.”