AI Poetry, Orlando and Raves: The Another Man Field Guide

- TextBen Perdue

All aboard a freewheeling train of thought via random literary connections and strange musical attractors. Calling at: AI poetry, Orlando, Spiral Tribe raves and the past, present and future of Africa

BLISS TO BE ALIVE

A musical mystery tour from Whitby to Deià via the Berlin underground.

As seafood-based rock legends go, it doesn’t share the clickbait grot of Led Zeppelin’s mud shark, but Leeds indie band Cud’s prawn myth is just as controversial. Their song Only a Day in Clichy became Only (a Prawn in Whitby), from 1989’s When in Rome, Kill Me, after their manager saw renowned vegetarian Morrissey eating prawn curry in a local Chinese restaurant. Zeppelin’s shark meat groupie sex-toy rumour was actually about Vanilla Fudge, and Mozzer turned out to be a lookalike, but the power of storytelling remains the same. The connection is made.

By 1989 The Smiths had split, Johnny Marr had joined Electronic, and a pre-toxic Morrissey was riding on the success of Viva Hate. It was also the year – coincidence, or fate – that New York rapper JPEGMAFIA was born, whose track I Cannot Fucking Wait Until Morrissey Dies, from the 2018 album Veteran, deftly states his views about the singer today. As for The Smiths, the rise and fall of their frontman shouldn’t detract from the band’s legacy, written partly in the impact of This Charming Man and its flowerstrewn video that perfectly translates how their dour camp took a blunt instrument to 80s pop.

When These New Puritans came on stage at The Dome in Tufnell Park earlier this year, touring their recent Inside the Rose, drifts of flowers reappeared, banked against the drum kit. They elevated the idea of floral props into a fleetingly beautiful backdrop to their music’s dreamlike descent into dark nature. The radical tone was shaped in the band’s Berlin studio.

“Berlin is a good place to follow your instincts,” says the band’s Jack Barnett. “We set up in a 50s DDR recording facility where they produced radio plays and propaganda. I’d ride through seas of broken glass to get there, chemicals from the cement works blowing in my face. Once, I saw two men fighting. One was swinging a metal pole at the other, but every time he swung, his trousers fell down round his ankles, showing his bare arse. He’d just pull them up and swing again. There’s nothing like persistence. Or Berlin. It’s a good place to be nocturnal.”

That’s how artist Seana Gavin felt when she arrived there in 1996, after a summer raving across Europe with Spiral Tribe’s sound system. The photographs she took that August, shown this year at her Spiral Baby exhibition at Galerie PCP in Paris, bring to life the creative freedom and lack of police authority she experienced. “There was a real punk mentality and energy,” she says. “If you were a young traveller passing through you stayed in squats for free, not hostels. Twenty of us slept in a room, which was a boxing ring. And it was run by militant anarchists, and had a bar, cinema and sauna.

“It wasn’t long after the Berlin Wall had come down, so it was a transitional period in time. I remember seeing random furniture on the streets that people had turned into installations and artworks. The walls of the streets were covered in graffiti, and everywhere I went, I found street mimes, poets and performance art.” This feeling of flux is picked up again by photographer Brad Feuerhelm, editor-in-chief of visual culture archive American Suburb X, in his new book Dein Kampf, published by Mack. Shot in modern-day Berlin, the images capture a pervading grittiness that endures.

“The city, though it still had fragments of previous ideologies pushing to the surface from its troubled past by way of its architecture and monuments, had also turned into a commercial Disneyland,” he says. “The citizens and ghosts of the past shared a distension from the ghosts of its future; high-rise advertisements overlooking the trinket vendors by Checkpoint Charlie.”

Writing about Berlin’s emerging club scene for The Face in 1992, the late Gavin Hills, voice of a generation of young British men swapping football hooliganism for acid house, discovered a hedonistic underground rooted in its avant-garde past. “You should understand, things have always been hardcore here,” said Johnnie Tresor, a deep-eyed young East Berliner who earned a crust from the shady club circuit. “Always the extremes.”

“Tresor isn’t strictly legal,” Hills wrote. “The risk is minimal as, unlike the bothersome bobby, Berlin police don’t seem to be worried about evening excesses. It was this tolerance that enabled Berlin to blossom in the late 20s into the liberal bohemia recorded in Christopher Isherwood’s novels. People stripped off, danced, abused drugs and indulged in their sexual preferences under the eyes of a tolerant, often indulgent police force. Germany is seen from the outside as soaked in authoritarianism. But there is a rival liberal tradition, and this is enabling the current scene to emerge from a reborn city.”

The book of Hills’ collected writings, released in 2000, three years after his accidental death, reveals a young journalist driven by love, idealism and chasing the party. His ability to capture the moment is summed up in its title: Bliss to Be Alive. The same sudden sense of clarity that inspired DJ and sound producer Yasmina Dexter, aka Pandora’s Jukebox, to create this exclusive playlist – soundtrack to a memory of Mallorca. “I’m in the car with my friends, driving to Deià for dinner,” she remembers. “Windows down, breeze blowing my hair, and golden sun washing over the beautiful landscape opening up before us. Summer tunes on full blast to hug it all up. I stopped and thought: ‘This can’t get any better, this is happiness, take it.’”

Let’s Make the Most of Our Time Here – Bruce

Dark River – Coil

Sentiment Océanique – Basses Terres

Kathy Lee – Jessy Lanza

Heaven – The Rolling Stones

Xerrox 2ndevol – Alva Noto

Planet Caravan – Black Sabbath

(Three Fingers of) Love – Art of Noise

L’Hôtel – Yello

Half Light of Dawn – Abul Mogard

Summer Madness – Kool & the Gang

OUR MYTHS, OUR SELVES

There’s a reason why we stopped giving computers human names. The balance of delinquent elegance in author and activist Jean Genet made him the perfect anti-hero. His seductive characters are autobiographical: rogue icons who subvert traditional masculine values by blurring moral ideals until concepts like courage, deceit and survival become impossible to decouple. “I recognise in thieves, traitors and murderers, in the ruthless and the cunning, a deep beauty – a sunken beauty,” he said. His semifictitious adventures appeal to both our primal and more nuanced selves, transcending the boundaries and sexual norms of society. Which explains their impact on artists like the Fat White Family, and how Prisoner of Love, his posthumously published account of being embedded with Palestinian fighters and the Black Panther Party, became the creative bedrock for the lyrics and video of Feet, from their 2019 album, Serf’s Up.

Fragrance may be a less obvious area for Genet to have influence, but the Brooklyn-based artist Parid Cefa’s Couteau de Poche project – named after The Thief’s Journal’s flick-knives – celebrates the novelist’s irreverent attitude through scent. Cefa’s unisex perfume Fumabat is a nod to “intellectual renegades” like Burroughs and Caravaggio, updating retro notes of oak moss, patchouli and vetiver with a new edge. “Like Genet, they were geniuses who didn’t obey the law,” he says. “But Fumabat could have had a different name and retained its character. In the same way Mozart’s Lacrimosa, or Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah could be about love, if the lyrics and title changed.”

If character is what counts, does a work’s creator need a human personality? Or could our next generation of flawed geniuses be machine minds? To test this, visionary technologist and artist Ross Goodwin fed the title Intellectual Renegades into his latest artificial neural network language model – or AI poet – called GPT-2. “It won’t ever have a human name,” he warns. “Anthropomorphising them can only have negative consequences as the technology improves. The model that created this poem was at iteration 466,944 of training after running on an Nvidia P40 GPU for 330 hours, on about five million words of handpicked modern poetry. But it’s still learning, so will only get better.” This is what the AI wrote for us:

Intellectual Renagades

I just returned from a visit to my friends

and the monastery

my body covered with tattoos.

It seem you would have put out

a little cigarette but I wasn’t looking for that

out of the enzymic field.

I just started dancing and sat there

stiff as a blind man

hisself, the kind of thing he does

when it’s his own country

staring at him

and tells him his country

is holding him back.

Isn’t that so why we exile him

from our shores? And the woods

for the resuming of our woods?

The woods are woods

and we must write about them

the way our parents did

when they were a boy

and I am just a young man

caught in the kind of conversation

that was always half-spoken

in the silent resort

we could tell our children

the one thing that was special

about their foreignness

was the kind of conversation

and outside of us in the outside

there was still the uncomfortable dance

of our voices growing increasingly abstract.

If our poets can be programs, we’re living the future now. So, where does that leave history? According to Marlon James, author of the African fantasy novel Black Leopard, Red Wolf, we’re living the past now too. “Talking about time in Africa, and African stories, we have to talk about continuum,” he said in his Tolkien Lecture on fantasy literature at Pembroke College, Oxford. “There is a reason why black people in the diaspora still speak present tense. I talk about a hundred years ago and use present-tense verbs. I don’t think we realise it’s because, for a lot of the nations and tribes we come from, it’s a continuum. If your grandfather is not really dead, and his spirit is just in the iroko tree, and he appears at the noon of dead and chills with you, then death is just part of that continuum.”

When past, present and future exist simultaneously, folded and stacked instead of linear, Africa’s myths and monsters can exist in a dialogue with its science fiction, in a kind of creative cognitive dissonance. Referring to ancient Rome in a quote on Gucci’s 2020 Cruise show invites, the French historian Paul Veyne wrote: “Only pagan antiquity awakened my desire, because it was an advanced world, because it was an abolished world.” Primal and sophisticated, analogue and digital, sorcery and science. Like the art nouveau designer Carlo Bugatti’s genre-agnostic throne chairs inspiring the Afrofuturist interiors of Black Panther ’s Wakanda. Or dub pioneer Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry imagining Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line – a 1920s shipping company created for the African global economy – embarking on an intergalactic voyage on African Starship, from his 2019 album Rainford.

Time as a continuum, in the context of Afrofuturism, is a core theme in the work of artist Zak Ové, curator of Somerset House’s summer exhibition celebrating black creativity, Get Up, Stand Up Now. Pieces like his Time Tunnel, a series of dials, were designed as catalysts for aligning past and future in the now. And after Marlon James stayed with the collector who owns it, Time Tunnel inspired James to contact Ové about how continuum could be defined using the artist’s found objects, as well as words. “At the back of the room there’s always this connection to Africa past, and Africa future,” says Ové. “In mythology, medicine and African religions. Working in Trinidad, I got into the history and culture of carnival, and it’s importance to Afrofuturism. Because behind the masks and costumes was this idea of escaping colonialism by breaking its thinking. If you could transform into a character, it became a way of using performance art as a way out, shape-shifting through dance and movement. The timelines are fascinating. Dancers play the devil covered in mud and indigo blue to protect your soul from evil, and mud linking to Yoruban culture where it was used as a kinesis to the earth. To connect with your extraterrestrial self. Afrofuturism is obsessed with these links, like the connection between Dogon people and the Sirius binary star system. How can this African culture, from the beginning of civilisation, have a cultural relationship with planets we can barely see?”

ALL I WANT TO BE

“We write, not with the fingers, but with the whole person.” Virginia Woolf, Orlando

When guest-editing the 2019 summer issue of Aperture, Tilda Swinton drew upon the transfigurative themes of Virginia Woolf’s novel, Orlando – about an Elizabethan nobleman who lives for three centuries without ageing, mysteriously shifting gender along the way, and basis for Sally Potter’s 1992 film, starring Swinton in the lead role. Her accompanying New York show included images celebrating openness, curiosity and human possibility in the same way, from Collier Schorr’s photographs documenting model Casil McArthur’s transition, to the hybrid bodies captured by Viviane Sassen’s classical statues at Versailles. “Woolf wrote Orlando,” says Swinton, “in an attitude of celebration of the oscillating nature of existence. She believed the creative mind to be androgynous. I have come to see Orlando far less as being about gender than about the flexibility of the fully awake and sensate spirit.”

“Don’t call me Marc. Call me Coco, that’s my stage name. After my transition, my name will be Eve-Claudine.” Swinton’s oscillating nature of existence resonates with the multi-layered life of Coco, the performance artist, transgender activist and fashion model whose story plays out in a new photography book, Coco, shot by her lover Olivier G Fatton. His photo essay follows the journey of her sex reassignment surgery through intimate portraits and impromptu fashion shots, the only record of an intense existence on the fringes of society that was cut short by suicide. “Coco was incredible!” Fatton remembers. “Smart. Polymorphic. So far ahead of her time.” She was an enigma who suffered from being born male, but also recognised how being transgender made her uniquely desirable in the early 90s fashion world, and how she would lose that by becoming a woman.

Using transformation to accentuate rather than move away from masculinity, the artist Alex Foxton explores the expressive side of male image, bringing to life the vulnerability and tenderness that men suppress. “I paint them how I see them,” says Foxton. “Men are sensual, they always have been, and it’s problematic to deny that.” His recent lipstick portraits on paper, shown at the 0fr. bookshop and gallery in Paris, illustrate one approach, while his depictions of historical characters – Napoleon as a pirate, Nelson in a bright pink uniform – aren’t subversive for the sake of it: they create a tension between romance and kitsch, lending them the sense of an interior life. Their physicality is boldly emphasised. “That distortion is a result of trying to give the figures expressive power,” he says. “It’s more lifelike that way – they have more presence. When I’m constructing a powerfully masculine figure it’s natural that they end up with huge shoulders and giant hands.”

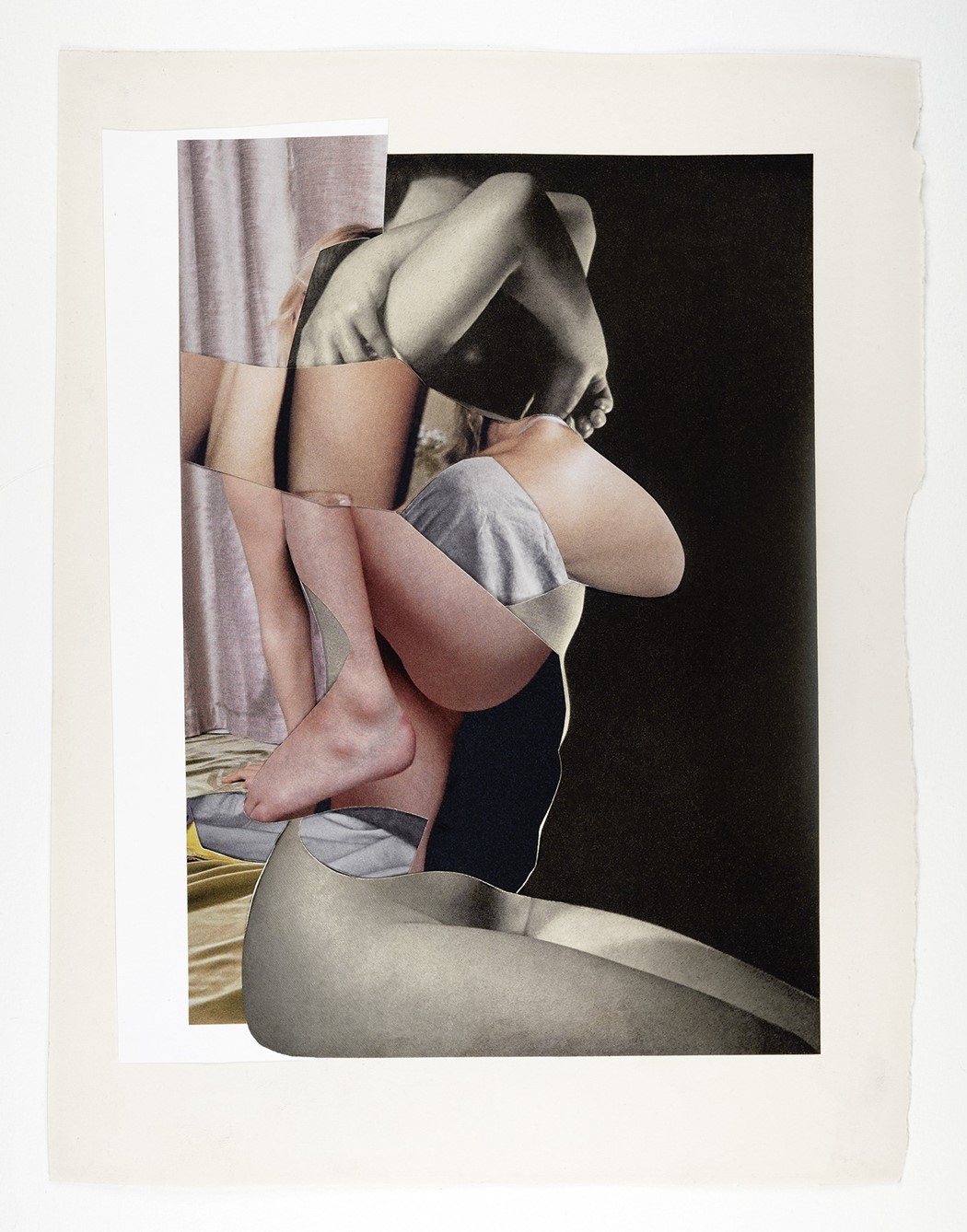

The narrative power of distortion drives collage, merging unrelated cut-up elements until a story appears. K Young is an artist using collage to form original images with the credibility of a photo, maintaining enough reality to describe a figure in a believable space that doesn’t actually exist, but feels like it could. “At the same time,” Young says, “the act of abstracting, deleting, sparing and omitting also allows the picture to be viewed not as a static snapshot in time like a photograph is, but a collection of glimpses, moments and suggestions; almost like a memory or dream. Place and time are kept vague. This expands the story and actively asks the viewer to make sense of what is happening; they have to create their own meaning.”

But if this process of deconstruction were reversed, could the same story be told using the source material? A series of unrelated images? Because this is what an Instagram feed can be: a stream of posts that tell its owner’s story, true or otherwise. To explore the narrative capability of unconnected moments, designer Miro Bijelich, whose Telepathic People feed has a bio that reads “Love, sex, money & fame. Desire, lust & sin”, created this exclusive visual anecdote. Four found photos were brought together to construct an original character, complete with backstory, introduced by Bijelich like this: “The lonely boy with the rat tail, breeds sugar gliders, loves his Venus fly trap and rides an off-road motorbike for kicks.”

Ultimately, the thread that ties all of the above together is identity. Or, more specifically, shifting identities, something that the influential make-up artist Thomas de Kluyver understands. Growing up in Perth, Australia, in the early 2000s, he and his friends used make-up as a form of self-expression at a time when you were either gay or straight. “There wasn’t anything inbetween,” he says. “So we explored gender and sexuality without necessarily knowing what to call it.” This is why personal spaces such as the bedroom, feature so heavily in his book, All I Want to Be, published by IDEA and shot by photographers including Sharna Osborne and Harley Weir; they are safe places to experiment with creativity and identity.

“Because the beginnings of these things are always formed in the spaces where we feel most comfortable,” de Kluyver says. “For the first time gender categories are disappearing, and being individual is celebrated more than ever, and I love that authenticity. Like I love scars and beauty spots and birthmarks, because they give people character. Today I’m wearing chipped nail polish and feel really comfortable, because it connects my masculine and feminine self and that’s OK. Just because you’re exploring one part of yourself doesn’t mean you have to be that forever, you know. It’s about what’s right for you at the time, and that’s what I’ve fought so hard for in my work. Going different ways is what’s interesting.”

THE WAKING HOUR

Or the butterfly effect of Roxy Music having tea with Dalí. It struck Bryan Ferry that he was famous when Salvador Dalí asked to meet Roxy Music in Paris. Recounting their night together decades later for the Daily Mirror, he depicted a suitably eccentric happening. “We had to sit on a crocodile, then went out to dinner in a Cadillac with these six amazing blonde models, and ate with a waiter behind each chair,” he said. “Dalí didn’t speak any English, but it didn’t matter. To me, that was just the most amazing experience for a working-class boy from the northeast.”

In her memoir, Guess Who Is the Happiest Girl in Town, published by Edition Patrick Frey, socialite and call girl Susi Wyss writes about belonging to Dalí’s entourage in the 70s and being a feminist outrider for sexual liberation. During one high-octane exploit, at yet another tea party, he nicknamed her ‘The Train’, after she missed one when things took an orgiastic turn with some handsome twins. “Dalí was thrilled to bits about it and offered to buy me a plane ticket,” she remembers. “He had his male secretary arrange everything.”

“Even without his art, he deserved his title of ‘Maître’ a thousand times over,” says Wyss. “He ruled in the kingdom of intellect and creation. Always surrounded by his menagerie of extraordinary creatures, he had the gift of asking special questions and getting special answers from people who ordinarily had nothing to say.”

Brian Eno would beg to differ. His own account of meeting Dalí with Roxy Music, told to Uncut magazine in 2005, paints a more lacklustre picture: “We met in a Paris hotel in 1973. Nothing much happened, nothing much was said. It was very much a pose-fest. Salvador had arranged for all these photographers to be there and all he did was make faces. The meeting was not embarrassing but it wasn’t incandescent either.” Still, he couldn’t distance himself from the artist’s influence, because in addition to being a track on Trout Mask Replica by Captain Beefheart, Dalí’s Car is the name of a live bootleg album from Eno’s first solo tour in 1974.

Cars and Dalí go way back; they were a constant in both his life and art. It’s no coincidence that a Cadillac picked Roxy Music up for their date, as the all-American motors were a recurring theme for him, appearing in his sculptures and paintings, and given by him as gifts – including one for his wife Gala, that’s now permanently parked at the Museo Teatro at Figueres. She used it to taxi him across the US in the 1940s, because Dalí didn’t drive.

In 1984, Peter Murphy’s band Bauhaus, having split after Burning From the Inside, a fragmentary album he barely worked on thanks to pneumonia, the frontman formed a new band, Dalis Car, with ex-Japan bassist Mick Karn. They only made one recording, The Waking Hour, released later the same year. More memorable than the music is the album artwork, a detail from Daybreak, painted by American symbolist Maxfield Parrish in 1922 – the most commercially popular art print in existence, and an oddly fitting statement for such a niche band.

Camille Vivier carries the same imaginary visual language that defines symbolism, driven by its mystical and erotic themes, over into the realm of photography. The work in her latest book Twist, published by Art Paper Editions, exists where those fictional worlds collide, as her enigmatic nudes encounter rethought classical sculptures, taking the viewer on an otherworldly trip almost as strange as sitting down to tea on a crocodile.

This story originally featured in the Autumn/Winter 2019 issue of Another Man, out now.