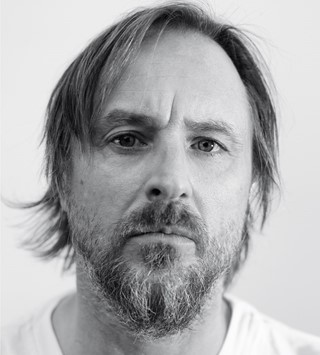

Frédéric Tcheng talks through his new documentary film about the famed designer, which features unseen archival footage and a candid interview with Liza Minnelli

- TextHannah Tindle

Beyond the decadence of disco, Studio 54, Ultrasuede, sequins and illicit substances, the story of famed – and at times mythologised – American fashion designer Roy Halston Frowick is predominantly the tale of an ambitious business venture gone awry. Director Frédéric Tcheng’s (Dior and I, Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel) new documentary, which is released worldwide today, investigates Halston as both a man and a brand, exploring Frowick’s ‘sky’s-the-limit’ vision for fashion in 70s and 80s New York. It was a vision that was perhaps just too ahead of its time: in a bid to render his high-end label accessible to all of the US, the Iowa-born designer was forced into selling off his company and, by proxy, his name.

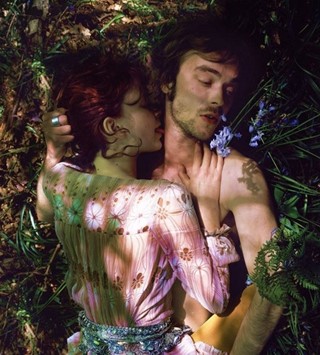

The story is told through the eyes of Tavi Gevinson, who plays the role of a committed journalist in the cutting room, piecing together lost and destroyed material that documented the life of Halston. Here, Gevinson narrates the documentary much like a detective, with the director taking the viewer along a gripping, non-linear journey in the spirit of film noir. Halston is moving, hilarious and painstakingly researched, with previously unseen archival footage that will cause fashion history fanatics to jump out of their seat with joy (I almost did). In addition, cameos from the women who were closest to Mr. Frowick – including Liza Minnelli, Elsa Peretti, Marisa Berenson, Pat Cleveland and his niece, Lesley Frowick – provide an unprecedented and emotionally charged insight into his psyche, punctuated by testimonies from the business investors who helped to destroy it. Here, Tcheng tells all.

Hannah Tindle: Why did you choose to make a film about Halston in 2019?

Frédéric Tcheng: The film came to me about four years ago through my producer who had made contact with Halston’s niece, Lesley [Frowick]. She had written a book on his life. I was trying to move away from making fashion documentaries so I initially said, ‘thank you, but no thank you’. But then I read the book and started researching what I could find on Halston, because I didn’t know anything about him, really. The story was just so incredibly dramatic that I couldn’t say no to it. I think it resonated with me on a deep level because of the business side of the story. I was at a point in my career where I had so much interaction with the corporate world and those interactions could be very painful and traumatic. As a creative person, you’re faced with the wall of corporate interest – and those people speak an entirely different language. In the fact that Halston lost control of his company in the 1980s, I saw a story that would allow me to investigate this socioeconomic change from the point that Ronald Reagan came into power and deregulated the financial markets. Halston was almost the first casualty. And this is the world we still live in today.

HT: Would you say the documentary is a cautionary tale to creatives working in fashion today?

FT: That’s how the story of Halston is usually understood, but I didn’t want to make him the victim. I think he was such a life force and he believed in trying – making things happen at any cost. There’s a song that I included in the middle of the film that Liza Minnelli sings in Liza With a Z – Halston did the costumes for this, of course – called Yes. For me, it encapsulates what I was trying to say through Halston’s story: ‘if you don’t play, you’ll never win’; ‘nothing’s gained if nothing’s tried’. That’s what I was trying to communicate with the audience. He very consciously made these daring and controversial choices, but they allowed him to step up to the next level. He was never someone who was going to be content. He was always pushing things forward. I think that’s beautiful. It’s about saying yes to life and not being afraid.

HT: Liza Minnelli was very clear about what she would and wouldn’t say in the film. How did you approach interviewing her and other key subjects?

FT: It was very tricky to gain everyone’s trust because the story of Halston has been so sensationalised over the years. It’s typically characterised by decadence, partying and Studio 54 – and of course that is part of it. But I think that everyone in his inner circle remembers the full picture, which is much more complex. Yes, he had his moments of failure, but he also was a great person. It was important to show to the different subjects we interviewed that I was interested in the whole of Halston, and not just the sensationalised parts. It helped that my previous films were also fair in approaching their subject matter and cast a very human light on people. So it was a process of discussion. With Liza being so close to Halston, it really took a while to convince her. Even when we were filming she was so nervous about saying something that was wrong. It was really touching actually, to see how she wanted to do justice to her friend’s legacy.

HT: Do you feel that you also got to know Halston quite intimately during the process of making this documentary?

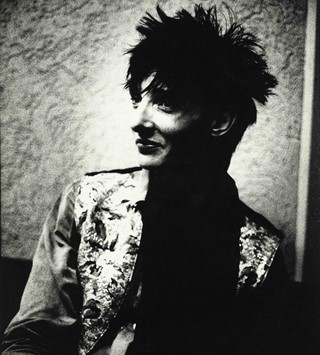

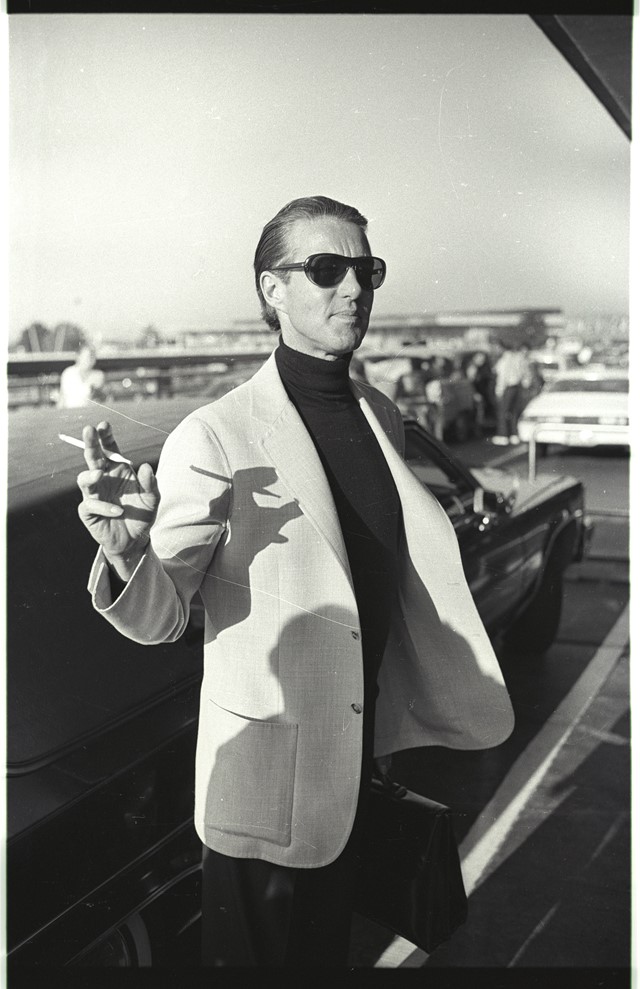

FT: Absolutely. I was compelled to find out who the ‘designer behind the dark sunglasses’ was. He was always creating this persona and putting this mask on – he was such a brilliant image-maker that sometimes the image concealed the human being behind it. That’s why we did so much research. And honestly, I’ve never done as much research for anything as I did for this film. We edited about 200 hours of footage. We were relentless with archives. We were digging and digging and finding things that had never been seen before – like the NBC footage of Halston preparing to go to China. That had never been broadcast. This particular film was a gold mine because you see him completely unedited and you realise how obsessive he was; how he was such a perfectionist and how he drove his team to the brink of insanity with his vision.

HT: Was Carl Epstein – the businessman ultimately responsible for Halston’s downfall – reluctant to speak on camera?

FT: Let’s put it this way: he was both reluctant and eager. And that’s what I like about Carl Epstein, he’s a very complex character. On one hand, he was driving our lawyers mad amending the release forms, and his daughters were very keen for him not to do the film because they were concerned he would be painted as the villain. But if you know anything about Carl Epstein, and I think I try to show that in the film, he was very interested in the glamorous aspect of the fashion world. He was very seduced by it. And he talks about that all the time – the fact that Halston had designed a crown for him, that he still had on his mantelpiece and puts on in the film to show us. He was desperate to tell his side of the story, in a way.

HT: Did you get the chance to see any of Halston’s archival clothes during your research?

FT: Yes – the dress that Tavi wears at the end of the film was originally worn by Lauren Hutton in one of the Vogue spreads. It’s really early Halston, 1973, or something like that. It was amazing to see them on the body, actually. When they hang on the rail, they just look like a couple of pieces of fabric. They don’t have ‘hanger appeal’, as you might say. It’s only when they interact with the body that the clothes come alive; become magic. Unfortunately, I don’t think this has done Halston any favours and I wonder if that’s why he hasn’t had the retrospective show he deserves yet. His clothes are made for movement – not staying static on a mannequin.

HT: Are you sure you don’t want to make any more fashion documentaries?

FT: I’m fascinated by fashion and the power it has to reflect society and culture. I think it’s an incredible prism through which to see life. I think the art world is very interesting too and is going to be the subject of a documentary I’m working on at the moment. I tend to gravitate towards stories about the creative process. So you know... Never say never.

Halston is out now.